Bonfire of the ‘Illegalities’? China’s New Immigration Law and Regulating ‘Illegal Work’

Posted:

Time to read:

Guest post by Mimi Zou, Assistant Professor, Faculty of Law, The Chinese University of Hong Kong. Her current teaching and research interests are in employment law, contract law, and Chinese law. This blog post is based on a working paper that was presented at the Refugee and Migration Law Discussion Group, Faculty of Law at the University of Oxford, on 11 February 2016. Mimi would like to thank Ms Yaolin Wang for her assistance with this post.

Much scholarly and policy attention on Chinese migration issues to date have focused on the internal migration of rural migrant workers to the fast-growing coastal and regional cities over the past three decades. Yet, the ‘factory of the world’ is now faced with a rapidly contracting workforce in the context of an ageing population. The number of ‘core’ industrial workers, born in the 1980s and 1990s under the ‘one-child policy,’ will decrease more quickly than other segments of the population. Some have forecasted that China will hit the Lewis turning point in 2025, with a projected shortage of 137 million workers by 2030.

At the same time, in its rise as a global economic power, China has become an emerging destination for international migrants from developed and developing countries. In 1978, only 229,600 foreigners (that is, those without Chinese nationality) had entered China that year. In 2014, there were 26.63 million inbound foreigners, many of whom include tourists, students, and business travellers.

In the 2010 National Census (which for the first time included foreign nationals), there were 593,832 ‘persons with foreign nationalities’ (excluding Hong Kong, Macao and Taiwan) lawfully resident in China for at least six months. Among this group, the number of person engaged in paid employment has increased from 74,000 in 2000 to 220,000 in 2011. There has been the emergence of large ‘foreign enclaves’ in some cities. For example, unofficial estimates of the number of African immigrants residing in the economically prosperous coastal city of Guangzhou are between 100,000 to 200,000 people.

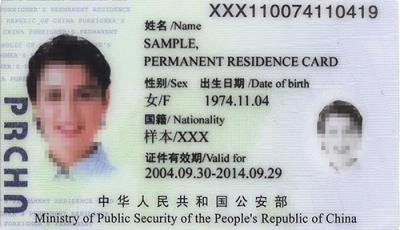

A legal framework to regulate the entry, residence, and employment of the growing number of foreigners in China has developed in a slow and piecemeal fashion. Until the late 1970s, China had in place strict controls over the entry and exit and the activities of the very small number of foreigners permitted to be in the country. In the 1980s, as China commenced economic reforms, there were some efforts aimed at attracting highly skilled ‘foreign experts’ to be employed by government agencies and departments. The most significant legislation to be introduced was the Law on the Administration of Entry and Exit of Aliens 1985. During the 1990s, there was a substantial increase of foreigners as China’s market liberalisation policies expanded. The State Council’s Rules on the Administration of Employment of Foreigners in China 1996 laid down more detailed rules and admission criteria. After China’s accession to the WTO, a ‘green card’ scheme was introduced in 2004 for long-term highly skilled ‘foreign talents.’

Administrative responsibilities for regulating foreign workers have been spread out between the Ministry for Public Security, the Ministry for Human Resources and Social Security, and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA), and these departments’ local branches at provincial, municipal, and county levels. There has been extensive criticism of the uncoordinated division of labour and responsibilities among the different departments at various levels.

In recent years, there has been an increasingly hostile socio-political climate in China towards the presence of foreigners throughout the country. Against this backdrop, Chinese policymakers introduced the Exit and Entry Administration Law 2013 (EEAL). The EEAL has been underpinned by a key policy goal of tackling the so-called ‘three-illegalities’ (‘sanfei’) of illegal entry, illegal residence and illegal employment.

As the state attempts to regulate who may cross its borders, reside in its territory, and participate in its labour market as well as determine the conditions of their entry, residence, and employment in its territory, immigration controls construct a range of personal legal statuses which have implications for migrants’ work relations.

As Anderson puts it, immigration controls can mould certain types of employment relationships in three ways: first, the conditions of entry, like a labour market ‘filter,’ can create certain categories of entrants based on skills level, earnings, sector/occupation, and other demographics; second, immigration controls can directly and indirectly impose restrictions and conditions on migrants’ work relations; and third, immigration laws, policies, and practices can produce ‘institutionalised uncertainty,’ such as through the creation of ‘deportable’ migrants with ‘illegal’ status. Furthermore, the operation of legal rules can undermine these migrants’ employment rights and remedies where immigration laws have been contravened.

Applying this analytical framework to examine the regulatory design of EEAL regime, three main arguments can be made. First, the conditions of entry regime continue to emphasise the admission of highly skilled migrants. There remain limited designated legal routes for other types of labour and economic migration. A strict visa issuance system (that operates in a rather bureaucratic fashion) and the granting of broad powers to immigration officers for refusing a visa application or denying a foreigner entry to China (without any obligation to provide a specific reason) is aimed at deterring ‘unwanted’ immigration.

The links between insufficient formal channels of migration and the growth of ‘illegal’ migrants in certain sectors have rarely been articulated in policy or scholarly discourses in China. There have been growing numbers of irregular workers from Southeast Asia in the manufacturing hub of the Pearl River Delta, a region that has been experiencing rapidly rising labour costs in recent years.

Second, a migrant’s authorisation to lawfully work and reside in China is tied to a specific employer based on having a valid work permit and work-type residence permit. The migrant must also work for the employing entity as indicated on her work permit. Furthermore, the work permit is valid only in the geographical area specified by the labour administration certification authority. Illegal work is also defined as ‘work beyond the scope prescribed in the work permits.’ These restrictions on migrants’ labour market mobility can place them in a heightened position of dependence on their employers.

The precariousness of migrants’ legal statuses also has troubling implications for their access to labour law protections, which are predicated on the existence of a valid employment contract. The Supreme People’s Court has confirmed that where a migrant did not have a work permit as required by immigration law and has requested the court to recognise a labour relationship with the employer concerned (for a claim under labour law), the court will not support such a case.

Third, the institutionalisation of uncertainty under the EEAL regime is associated with a range of punitive measures on sanfei migrants, situated in a discourse of targeted enforcement by the state and other actors. The EEAL introduces harsher penalties for migrants engaged in illegal work, including detention and deportation. Meanwhile, employer sanctions are limited to fines. For the unscrupulous employer, gaining a competitive advantage from an exploitable migrant workforce may outweigh the risk of getting caught and being ‘punished’ with a relatively small fine.

The enforcement of the EEAL not only involves local public security bureaus and exit/entry border inspection authorities, but also actors beyond the state and at diverse sites such as the workplace and the public arena. Employers must report to local public security bureaus in a timely manner a range of circumstances, including the compliance of the migrant with immigration rules. Furthermore, a ‘whistleblowing’ system of reporting sanfei activities by the general public has been introduced.

The EEAL regime, situated in an increasingly prominent anti-sanfei public discourse, can produce a range of migrant statuses that are associated with multidimensional precariousness in migrants’ work relations and other aspects of their lives. To date, there have been very few analyses of the legal regulation of labour migration in China. My inquiry seeks to cast a spotlight on this heavily under-examined area, which is likely to become more important in the near future as the country confronts critical labour market challenges arising from major demographic transitions.

Any comments about this post? Get in touch with us! Send us an email, or post a comment here or on Facebook. You can also tweet us.

__________

How to cite this blog post (Harvard style):

Zou, M. (2016) Bonfire of the ‘Illegalities’? China’s New Immigration Law and Regulating ‘Illegal Work.’ Available at: https://www.law.ox.ac.uk/research-subject-groups/centre-criminology/centreborder-criminologies/blog/2016/02/bonfire- (Accessed [date]).

Share: