Guest post by David J. Danelo, director of field research at the Foreign Policy Research Institute, and a former US Marine. This post is the fourth installment of Border Criminologies themed series on Human Smuggling organised by Gabriella Sanchez.

As stories about human smugglers manipulating victimized migrants dominate international airwaves, internet readers on both sides of the Atlantic might think people who skirt European and American border regulations are second only to (or the same as) murderers or rapists along the descent of criminal amorality. In almost all migration narratives, modern smugglers are demonized as exploiting opportunists and dangerous rogues.

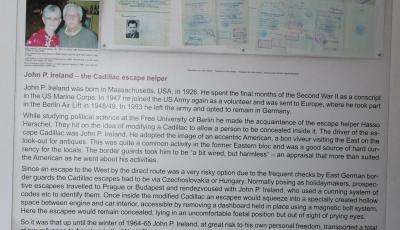

On the second floor of the museum, three rooms are dedicated to displaying the ‘heroism’ of men and women who, ‘at great risk to their own personal freedom,’ brought ‘refugees’ out of East Berlin to ‘freedom in the West.’ Placards with stories of the ‘escape helper’ backgrounds cover the walls. The most prominent display—featured on the museum’s official website—includes a model car with compartments near the engine block that could hide a person. Any smuggler today would recognize, and probably admire, the ingenuity and tactics.

According to the Checkpoint Charlie Museum display, soon after the Berlin Wall ascended, Ireland modified his Cadillac to include a ‘specially created hollow space between the engine and car interior.’ From August 1961 until early 1965, Ireland was one of several drivers in a smuggling ring organized by Hasso Herschel, who helped over 1,000 other East Germans escape through tunnels and hidden compartments. In three years, Ireland drove ten East Germans through the Berlin Wall checkpoints, breaking numerous laws in the process. The Checkpoint Charlie Museum, however, hails Ireland as a man who endangered himself to keep escapees ‘out of sight of prying eyes.’

The term ‘smuggling ring’ often brings to mind seedy images of mafia kingpins swapping cocaine stashes and trafficked girls. In West Berlin, Herschel, Ireland, and hundreds of other assistants are feted today as heroes. Standing in the Checkpoint Charlie Museum, it becomes difficult to judge harshly anyone who undertakes the risk of moving men and women from one border checkpoint to another. In this room, ‘criminals’ don’t seem to exist—only people who, for whatever reason, assume the complex task of taking men and women from chaos to safety. On a continent where smuggling has become demonized, it remains a perspective worth considering.

Any comments about this post? Get in touch with us! Send us an email, or post a comment here or on Facebook. You can also tweet us.

__________

How to cite this blog post (Harvard style):

Danelo, D. (2015) When Smuggling Was Heroic. Available at: https://www.law.ox.ac.uk/research-subject-groups/centre-criminology/centreborder-criminologies/blog/2015/11/when-smuggling (Accessed [date]).

Share: