Guest post by Mario Badagliacca, a photographer based in Rome, Italy. Focused on local realities and social issues, he’s currently working on long term projects on migrants and migrant communities, paying attention to the cultural aspects of migration.

It seems that for European governments, military action is the only plausible option to solve the current migrant crisis. During the past few months, we’ve seen no man’s lands being created along European borders: barbed wire, soldiers, search dogs, and torches at night patrolling wooded areas.

Italy is no exception. In fact, we have our own ‘front,’ and are sustaining our own ‘battle’ against migrants through identification and expulsion centres (Centri di identificazione ed espulsione or CIEs). In a previous post on this blog, I’ve explained in detail what CIEs are and how they operate.

Since that last blog post was published, only a year ago, the situation in Italy and Europe more broadly seems to have worsened. Dividing walls have reappeared in Europe after decades, and the Italian government is ready to open new ‘hotspots,’ structures where migrants will be identified on arrival. As established by the Dublin Convention, these people will have no choice but to remain in Italy, if granted political asylum. If instead they’re identified as ‘economic migrants’ or if they refuse to give their fingerprints, they will be taken to a CIE in order to be deported.

This perverse system of human rights violation is responsible for generating numerous contradictory situations.

The story of Lassaad Jelassi in my short documentary, Letters from the CIE, is a prime example. Lassaad has been living in Italy for 25 years. After getting in trouble with his resident permit, he was detained in the CIE at Ponte Galeria (Rome) for 4 months until he won his court action and was released. Lassaad now works as a cultural mediator in a centre for migrant minors in Rome. But the trauma caused by his forced detention at Ponte Galeria will never leave him.

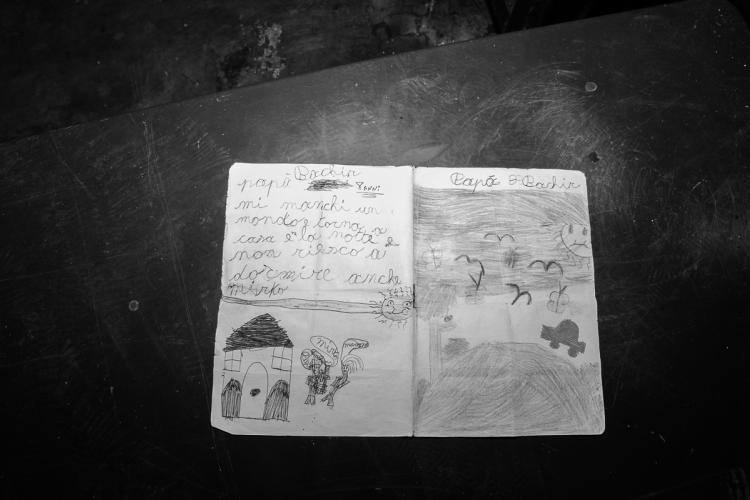

Letters from the CIE tells his story and uses pictures to illustrate daily life inside a CIE. The purpose of the video isn’t to give technical details on CIEs, but to virtually bring the audience inside one of these facilities. It’s a visit guided by Lassaad’s voice, recalling his daily life during those hellish months at Ponte Galeria. The intention of the video isn’t to just cover a story, but to make the viewer question the entire system.

When I started my research, I myself had been wondering what life in a CIE is like. What would be the dynamics amongst the detainees? What would be the gender dynamics? What forms of resistance people would use in order to put up with such inhumane conditions? And what would be their relationships with the CIE staff and police?

As a survivor, Lassaad was actively involved in the making of the film. We worked together on the script, which is based on his observations and experiences of Ponte Galeria. The work gave him the opportunity to process his own experience, to come to terms with it, and, once people showed interest, to find a way to tell it. In order to make the film more powerful to the audience, we chose to leave the original sound, recorded inside the CIE in Rome (which was only possible thanks to the skillful work of Enrico Grammaroli, sound technician and activist from the organisation Circolo Gianni Bosio).

The video production was made possible thanks to funds from the Documentary Photography Project 2014 of Open Society Foundations and in collaboration with the Archive of Migrant Memories (AMM), a Rome-based organization helping to archive migrants’ memories, and took place in both Ponte Galeria (Rome) and Palese (Bari). It wasn’t a simple project. It took me four years to obtain all the necessary authorizations to visit the CIEs. During each visit, everything I did was closely overseen by the CIE police, especially in Bari. Hiccups with funding and very few access permits contributed to the delay of the project. Although requested, access permits to other CIEs across Italy never came. The CIE in Turin, for example, never granted permission.

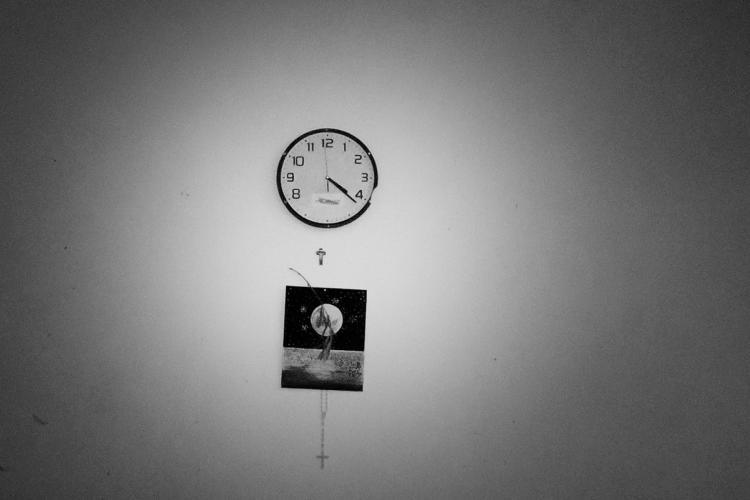

What I found most striking in the CIEs was the complete disorientation I felt once inside. The first time I visited Ponte Galeria, I struggled to find arguments, even imaginary, that would explain the reality of that place. What I saw was people in open air cages. The system of corridors and gates made me think of concentration camps right in the heart of Italian cities. Detainees experience the same disorientation, aggravated by the impossibility of justifying their presence there, because unlike prisoners in jail, these people haven’t been convicted of a crime. Italian laws aren’t very clear on this point. Officially, people in CIEs are not considered ‘detainees,’ but are referred to as ‘guests.’

At the same time, it’s very hard for lawyers to work for those who’re detained because Italian law on migration doesn’t give them juridical tools to defend the migrants and help prevent their expulsion. All of these factors produce a state of limbo, one of fear and anguish, in which prisoners live every day.

Mario’s solo exhibition, ‘Letters from the CIE,’ is at San Diego State University, USA, 2015 to 2016. For more information, see his website.

Any comments about this post? Get in touch with us! Send us an email, or post a comment here or on Facebook. You can also tweet us.

__________

How to cite this blog post (Harvard style)

Badagliacca, M. (2015) Letters From the CIE. Available at: https://www.law.ox.ac.uk/research-subject-groups/centre-criminology/centreborder-criminologies/blog/2015/10/letters-cie (Accessed [date]).

Share: