Guest post by Anna-Lisa Müller, senior researcher at the Department of Geography of the University of Bremen. Anna-Lisa is on Twitter @annalytika and online at annalisamueller.de and academia.edu.

Setting 1: Next month: Moving. Leaving a familiar place. Relocating in a (yet) unfamiliar environment. Writing lists of what to take with you. Some things are always on top of the lists, you hardly have to write them down to remember to take them with you. Then packing the suitcase(s). In the final minutes: tucking something in a niche in the suitcase.

Setting 2: Arrived in an unfamiliar place. Unpacked the suitcase(s). Put things from the suitcase on the shelves to create a feeling of ʻhome.ʼ Taking out the ʻsomethingʼ that found its way to the suitcase’s niche in the last minute of packing. Placing it on the shelf.

What’s important to establish a feeling of ʻbeing at homeʼ when you are a highly-mobile person, a transmigrant, a person who regularly crosses territorial and cultural borders? Generally, objects may help to create a familiar environment, no matter where you are or how often you move. The anthropologist Daniel Miller shows in his book The Comfort of Things how objects matter for people. He studied the inhabitants of a street in London, people who’ve often lived there for a long time, and shows in a thick description how they use very different kinds of objects―christmas decoration, toys, CDs, etc.―to stabilize their everyday lives.

In contrast to people who live a rather stationary life, transmigrants cannot normally amass a lot of Stuff (as a different book by Daniel Miller is called). Their lives are characterized by frequent relocations, and these relocations imply constant negotiations about what to take with them and what to leave behind. But this doesn’t mean at all that physical objects are not important to transmigrants.

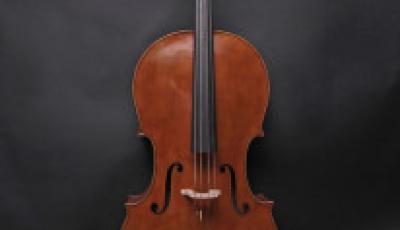

Data from my current research project show that everyday objects―pictures, books, or even a violoncello―play a significant role in creating senses of belonging in the places between which people move. The objects are constitutive for the migrants’ attachment to a place and for their situatedness during mobility. The migration biographies of the people interviewed in the course of my research project revealed two things: (1) important objects for transmigrants can be classified along the distinction mobile/immobile, and (2) the objects fulfill at least three different functions in their owners’ lives.

The objects’ classification run along the line of mobile versus immobile. Immobile objects, that is, objects that are taken on the travel by the migrant, remain in place when the migrant moves again. For one of my interviewees, originally from Venezuela, this was his motor scooter. At a certain stage of his migration biography, in Spanish Granda, this vehicle allowed him to explore the place where he lived and significantly helped to establish a sense of belonging to his temporary hometown.

This object didn’t only help the interviewee, Luis, ‘to focus on the place and to get the most out of the place.’ By being locally mobile on the scooter, he became an insider of local culture that even natives approached: ‘people from Granada asked me “can you recommend me a place?,”

Mobile objects are those things that migrants take with them, to which they feel so emotionally attached that they do all they can to bring them with. Such objects aren’t easily replaceable. They must also be small enough to be taken along. Small is relative though: Another interviewee has taken her violoncello to every place to which she was moving. It allowed her to get in contact with others in unfamiliar places, for example, by playing in an orchestra or taking private music lessons. The violoncello was a means to ensure that the people she meets share at least one interest with her: music. And it helps to keep up everyday practices, like playing an instrument. Maintaining everyday practices and relying on shared interests, then, helped to create a feeling of belonging to places as diverse as Buenos Aires, Tokyo, and Bremen. Thus, one function of mobile objects is that they can serve as mediators to establish senses of belonging.

So far, my research project shows that objects play an active role for transmigrant people to create senses of belonging at frequently changing places. The objects develop a certain ʻagencyʼ within their owners’ migration biographies and are faithful accompanists. These objects can either be mobile or immobile depending on whether they migrate themselves or not. Additionally, for those who frequently cross territorial as well as cultural borders, objects function in at least three different ways: to facilitate getting to know the temporary hometown and to blend with the local culture (e.g., the scooter, the clothes); to create a sense of ʻfeeling at homeʼ in changing places by ensuring that everyday practices can be kept up (e.g., playing the violoncello, using the laptop); and to store memories of past migration stages (e.g., clothes worn in other places).

Integrating general insights from the study of material culture into the study of transmigration will help develop the above interpretations of the role of objects for international transmigrants. Assuming that transmigrants develop a certain culture that shapes their practices, emotions, values, and so forth, the question then is in what sense material objects contribute to this culture of (trans)migration. Transferring insights from disciplines like cultural anthropology, archaeology, or science and technology studies open up the possibility to understand objects as co-constitutive for the social in this case of transmigration.

Any comments about this post? Get in touch with us! Send us an email, or post a comment here or on Facebook. You can also tweet us.

__________

How to cite this blog post (Harvard style)

Müller, A-L. (2015) International Transmigration, Senses of Belonging and Objects. Available at: http://bordercriminologies.law.ox.ac.uk/international-transmigration/ (Accessed [date]).

Share: