Post by Ingrid V. Eagly, Assistant Professor of Law at UCLA School of Law. This post is the final installment of the Border Criminologies Themed Week on Migration, Criminal Law and Criminal Justice organised by Ana Aliverti.

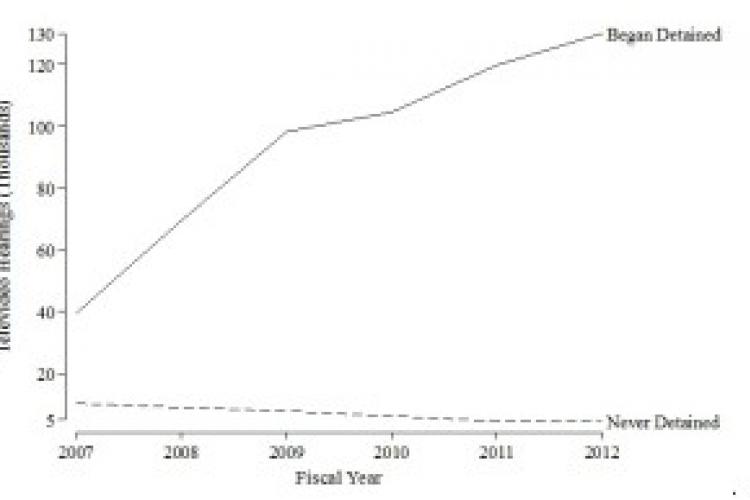

In a forthcoming article, the Northwestern University Law Review will publish the results of the first empirical study of the use of remote adjudication by televideo technology to decide whether immigrants will be deported from the United States. My study of televideo adjudication is based on detailed analysis of thousands of immigration cases contained in the immigration court’s own administrative database. In addition, I conducted site visits and court observations at major immigration courts and detention centers and interviewed immigration attorneys, prosecutors, and judges.

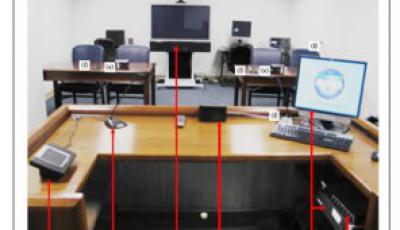

Televideo represents a new adjudicative approach that connects detained immigrants with the judge, prosecutor, and other court personnel via a bi-directional video stream. Courts equipped with televideo technology follow the same basic procedures as in-person courts, the key exception being that the immigrant litigant now remains at the detention facility and watches the court proceedings on a television screen in the facility’s video room. The judge remains in the traditional courtroom with his or her courtroom deputy and court staff and the immigrant is projected onto a television screen in the courtroom. Typically, the prosecutor, interpreter, and respondent’s counsel (if s/he has one) remain in the courtroom with the judge rather than traveling to the detention facility to appear on video with the litigant.

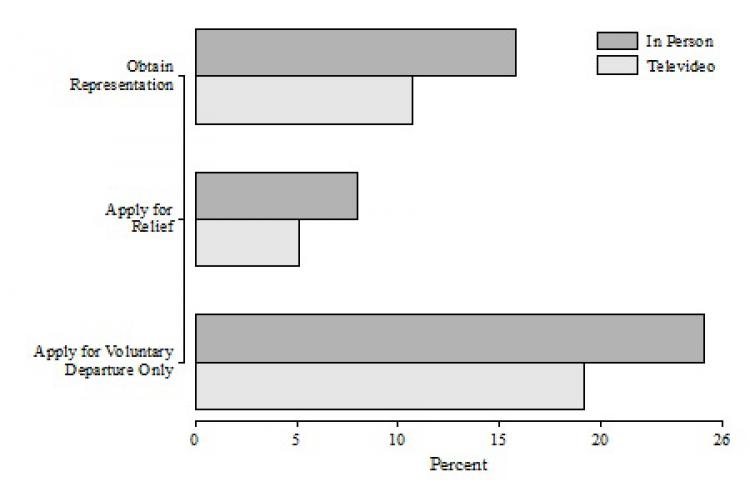

Examining the government’s implementation of televideo adjudication in federal immigration courts reveals an outcome paradox: detained televideo litigants were more likely than detained in-person litigants to be deported, but judges did not deny respondents’ claims in televideo cases at higher rates. Instead, these inferior results were associated with the fact that detained litigants assigned to televideo courts exhibited depressed engagement with the adversarial process—they were less likely to retain counsel, apply to remain lawfully in the United States, or seek an immigration benefit known as voluntary departure.

My on-the-ground assessment of the inner workings of detained adjudication suggests that a number of factors are at play in the depressed engagement of televideo litigants. Televideo litigants may decline to participate in a system they perceive as unjust or rigged to yield unfavorable results. Detained immigrants forced to pursue a case over a video screen often appear bewildered or confused and may experience the process as less ‘real.’ Placement away from the physical courtroom separates the litigant from other courtroom actors, including the judge, prosecutor, and his or her counsel. Detainees and their attorneys are frequently discouraged by the numerous logistical and technical difficulties associated with litigating televideo cases, such as unpredictable interruptions in the video feed, challenges in communicating with interpreters not physically present in the same room, and the impossibility of confidential attorney-client communication over a public courtroom screen.

Detainees removed from the courtroom by the video procedure may be less likely to understand their rights in the removal process, less likely to request a court continuance to find a lawyer, and, especially for those who cannot find or afford an attorney, less equipped to assert their claims and file the required paperwork. For judges, advising litigants of their rights can be awkward and less effective over a screen than face-to-face in the formal setting of a courtroom. Yet another factor that could promote televideo litigants’ waiver of rights is their physical separation from the courtroom audience, including family and supportive community members, due to detention facility rules that prevent the public from attending hearings at remote locations.

Opposition to remote adjudication has relied on the conventional wisdom that the practice unfairly tilts the balance against litigants at trial. My forthcoming article introduces an entirely new and serious concern into the debate: the potential of remote adjudication to interfere with meaningful participation in the adversarial process. This lack of participation matters because, with less attorney involvement and claim-making by immigrants, televideo cases are more likely to result in deportation. Moreover, although this article remains focused on the televideo debate in the immigration system, its finding of interference with access to justice is relevant in other contexts, such as administrative and criminal proceedings, which are increasingly turning to remote technology in hope of enhancing courtroom efficiency. So long as participation in the process suffers, remote adjudication cannot be defended as the modern functional equivalent of the traditional courtroom.

Themed Week on Migration, Criminal Law and Criminal Justice:

- Monday, 15 June: Crime, Justice and Migration (A. Aliverti)

- Tuesday, 16 June: Bail Denials and Beyond: Lopez-Valenzuela and the Role of Immigration Status in Criminal Justice (J.M. Chacón)

- Wednesday, 17 June: The Deportation Trap of Juvenile Transfers: How A Child Becomes A Desperado in the Eyes of the Law (J. Nogo)

- Monday, 22 June: Language Interpretation in the Criminal Courts: An Essential but Unstable Service (R. Seoighe)

- Tuesday, 23 June: The Function of the Criminal Law in the Prosecution of Refugees (Y. Holiday)

- Wednesday, 24 June: Mapping out a (Brief) Research Agenda for Border Criminology (M.T. Light)

- Thursday, 25 June: Remote Adjudication in Immigration (I.V. Eagly)

Any thoughts about this post? Get in touch with us! Send us an email, or post a comment here or on Facebook. You can also tweet us.

__________

How to cite this blog post (Harvard style):

Eagly, I.V. (2015) Remote Adjudication in Immigration. Available at: http://bordercriminologies.law.ox.ac.uk/remote-adjudication-in-immigration/ (Accessed [date]).