When it Comes to US Punishment, Noncitizens May be the New Face of Legal Inequality

Posted:

Time to read:

Post by Michael T. Light, Assistant Professor of Sociology at Purdue University, Indiana, United States. His research focuses on immigration, crime, and punishment. This post was originally published on the London School of Economics’ daily blog on American Politics and Policy on 24 October 2014 and can be read here as well.

In the wake of the most recent wave of undocumented immigration, a substantial amount of public and media attention has focused on the US response to unlawful migrants, particularly the role of deportation. However, increasing numbers of non-US citizens are being brought before the criminal justice system, and lost in this discussion is a full understanding of what actually happens to them when they are punished under US law.

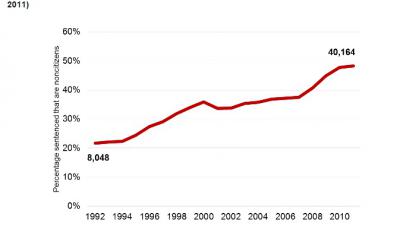

This is a major gap given that the number of noncitizens sentenced in US federal courts has increased nearly five-fold over the past two decades. As Figure 1 shows, by 2011 nearly 1 out of every 2 people sentenced in a US district court lacked US citizenship. Even scholars and politicians interested in legal inequality have largely overlooked the importance of citizenship, instead focusing on issues such as race and ethnicity.

However, in new research my colleagues and I analyzed nearly two decades of federal court records to examine whether citizenship has implications for differential treatment under the law. Three notable findings emerged.

First, national membership is now an influential marker of legal inequality in US District courts, such that non-US citizens―and especially undocumented immigrants―receive harsher penalties at sentencing than US citizens. For example, in 2008 96 percent of convicted noncitizens received a prison sentence, compared to 85 percent of US citizens.

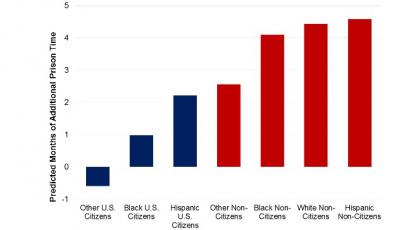

One explanation for this sentencing gap could be that it is a reflection of differences in criminal offending―noncitizens may, on average, commit more serious crimes or have more severe criminal histories. However, we found that even after we account for a host of factors that could potentially explain this difference, such as offense severity and criminal history, non-US citizens were still significantly more likely to be sentenced to incarceration than comparable US citizens. Further still, we found that among those who are imprisoned, noncitizens received an additional 3-4 months of prison time on average.

It’s important to put these results in perspective. When deciding whether or not to incarcerate, the sentencing gap between citizens and noncitizens is larger than the gap between racial/ethnic minorities and whites, between men and women, and between college-educated offenders and high school dropouts.

Second, citizenship status is more consequential for sentencing outcomes today than it was two decades ago, a finding that holds for both legal and undocumented immigrants. For example, in 1992 the odds that a non-US citizen would be incarcerated by a federal judge were roughly two times higher than a comparable US citizen. By 2008, the odds were over four times higher. This sentencing gap was most pronounced in federal districts that experienced the largest influx of non-US citizens since 2000. This suggests that part of the increased punitiveness against non-US citizens in recent decades can be linked to judicial responses to the changing demography of the US population, which witnessed an increase of roughly 4 million non-US citizens between 2000 and 2010.

Third, the punishment gap between citizens and noncitizens is not simply a reflection of well-known patterns of racial or ethnic inequality. Several factors point to this conclusion. One, because the federal courts collect information on both race and citizenship, we were able to separate out the independent effects of each in our analyses. Two, accounting for citizenship explains a substantial amount of the sentencing gap observed between white and Hispanic defendants, while race and ethnicity account for virtually none of the sentencing disparity between citizens and noncitizens. Three, as Figure 2 shows, every group lacking US citizenship—including white noncitizens—receives tougher sanctions compared to white citizens. In addition, for all races, noncitizens are sentenced more harshly compared to their citizen counterparts. For instance, while black citizens received an additional month of incarceration compared to white citizens, black noncitizens received 4 extra months. By focusing mainly on racial and ethnic differences under the law, previous research had underestimated the significance of national membership.

The Future of Legal Inequality

With over 22 million noncitizens currently in the US and international migration unlikely to cease any time soon, our findings offer important lessons for understanding the future of inequality under the law. For starters, it calls for a reorientation to our understanding of legal inequality. While the US Attorney General Eric Holder has decried racial and ethnic disparities in sentencing as “shameful” and has launched a series of reforms aimed at reducing bias in the justice system, the growing numbers of non-state members in US prisons and their treatment within the courts has received little political or public attention. Our research suggests a broader view of legal inequality is needed, one that includes national membership right alongside factors that have dominated conversations on disparities in the criminal justice system, such as race, class, gender.

In addition, our results may have implications beyond just US court rooms. As countries and economies continue to become more interdependent, international migration is becoming a permanent feature of many Western societies. And while the US often stands out on an international stage when it comes to crime and punishment, reports indicate that across Europe noncitizen prisoners have increased rapidly in recent decades―in both absolute and relative terms, similar to trends in the US. Understanding how non-state members fare in court beyond the United States will shed light on why we see these incarceration patterns, and hopefully in the process, help identify solutions for ensuring everyone receives equal protection of the law.

This article is based on the paper ‘Citizenship and Punishment: The Salience of National Membership in U.S. Criminal Courts’ in the American Sociological Review.

Any comments about this post? Get in touch with us! Send us an email, or post a comment here or on Facebook. You can also tweet us.

__________

How to cite this blog post (Harvard style):

Light, MT. (2014) When it Comes to US Punishment, Noncitizens May be the New Face of Legal Inequality. Available at: http://bordercriminologies.law.ox.ac.uk/punishment-noncitizens/ (Accessed [date]).

Share: