Guest post by Melanie Griffiths, ESRC Future Research Leaders Fellow at the University of Bristol. She has written on time, masculinity, identification, uncertainty, and ‘truth’ in relation to immigration detention and the asylum system. Follow Melanie on Twitter @MBEGriffiths.

Political promises to be ‘tough’ against migrants, slash immigration numbers, and increase deportations in the name of shoring up the border tend to resonate with the general public―except, that is, when it involves people well known and liked, and most especially when it involves loved ones. Despite these caveats, there have been a raft of changes recently to the management of people coming to the UK on the basis of relationships, as well as to immigration enforcement measures which impact already-present family members. Known as family (or marriage) migration and Article 8 deportation cases respectively, these issues affect not only migrants but British citizens, and lead to ever increasing numbers of divided families.

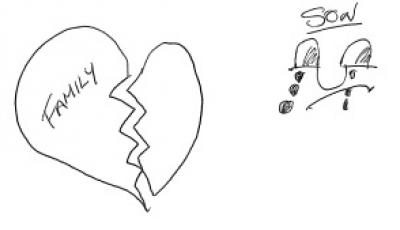

This post explores recent changes to the management of this area of British border enforcement and questions the implications for the conceptualisation and evaluation of families in migration contexts. It argues that in calling for their private lives to be afforded weight when balanced against the wider ‘public interest’ of effective immigration control, people are asking the authorities to recognise (1) that they have a family and (2) that this family matters.

When is a family not a family?

Whose family counts?

On occasion, the Home Office may accept the existence of a relationship, but dispute its importance. The argument is that only some family ties, in some circumstances, outweigh the public interest of immigration decisions such as deportation or the refusal of spousal visa applications. As a detained man facing removal put it to me, the Home Office felt that he could be a perfectly adequate father through the occasional telephone call from Abuja.

A number of questions are raised by these evaluations. Whose families matter? How many parents does a child need and does gender and ethnicity affect the perceived value of parents? Are the needs of British children greater than non-citizen children? Is the family life of spouses stronger than that of cohabiters? How relevant is the length of residence or immigration status of not only the foreign partner but the sponsor? What about income, ‘integration,’ or behaviour?

Restricting entry and expanding expulsion

On 9 July 2012, a number of changes were made to the management of family migration to the UK, including new restrictions on the entry of adult dependent relatives and increases to the minimum income threshold of Britons seeking to sponsor foreign spouses. Although the income requirement has disproportionate effects, with the result that some people will never earn enough to bring in their spouses, it was upheld earlier this year by the Court of Appeal (an issue I explore in greater detail elsewhere).

Alongside raising the hurdles for family members wishing to come to the UK, the Home Office is seeking to increase removals of certain people already in the country. This has been driven by political and media suspicion of the use of Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights, which includes the right to respect for one’s private and family life, to challenge deportation decisions (see press stories here and here). As a result, on 28 July 2014, several significant developments came into force through the 2014 Immigration Act, including alterations to the deportation chapter of the Immigration Rules.

Deporting daddy

- have a ‘genuine and subsisting’ relationship with a qualifying partner or child who would find the person’s deportation ‘unduly harsh;’ or

- have been lawfully resident in the UK for most of their life, are socially and culturally ‘integrated’ and would face ‘significant obstacles’ integrating in the country of return.

In other words, applicants must show that they’re effectively British in all but the strictest legal sense, or that the impact of their deportation on a (preferably British) close family member would be so severe as to be what the Home Office defines as ‘excessively cruel.’ A very cruel effect on a child would not meet the threshold; it must be excessive.

To demonstrate that family ties are important enough to outweigh the ‘public good’ of expulsion, then, integration is now important, including English language skills, financial status, and regular work. The citizenship and immigration history of both the foreign national and his or her partner or child matters, including whether a child was British-born or naturalised. Little weight is placed on relationships established when someone was in the UK unlawfully, or on private lives formed under a precarious immigration status.

Undercurrents?

Similarly, the view that it may be advisable to remove family members alongside a foreign offender if this ‘would allow the child to be raised in his own culture,’ (paragraph 3.4.8) raises the question as to what is implied by the term ‘culture’ and the circumstances under which it’s invoked. The implication that some people are less ‘culturally’ British than others, and that there’s an ancestral or cultural ‘home’ that they belong to more strongly, has been noted by others in relation to some Home Office decision-making (see this recent Free Movement blog post).

The system is also gendered. In assessing family ties, decision-makers are informed that fathers don’t always automatically have a legal parental responsibility. They’re instructed to assess if a parent is involved in decision-making about the child’s life, such as which school they go to, if they are active in the child’s day-to-day life, live with or near them, and how regularly they see them. Such factors may disproportionately count against fathers after break-ups, assuming that custody is normally granted to mothers. The rather odd Home Office assertion that a child can usually have no more than two parents will also raise difficulties for many modern families.

Current research

These developments raise a number of tensions at both the conceptual and policy levels, including between a child’s right to grow up with her or his parents, and the state’s right to assert its sovereignty through immigration controls. Such tensions reflect the contemporary face of the longstanding centrality of gender, class, and ethnicity in imagining and building the nation state, and enduring questions regarding the boundaries of citizenship.

I’m conducting ESRC-funded research founded on the recognition that mixed-nationality families are an area in which definitions of belonging are actively contested and present a rare space in which British citizens confront the immigration system. Through qualitative research with precarious male migrants in the UK and their British/EEA national partners, I’m analysing the relationship between ‘deportability’ (following De Genova) and family life. My research examines the impact of being at risk of detention or removal on experiences and practices of family formation, and questions the impact of immigration controls on family members who are not themselves directly subject to them.

Debates around the rights of citizens and non-citizens to make intimate choices in the face of national immigration objectives aren’t new. The policing of cross-border love has long been employed in defining the nation (see, for example, this recent blog post). However, as mobility becomes a reality or aspiration for increasing numbers of people, transnational ties and multiple-citizenship families will only grow in social, and therefore political, significance.

Any comments about this post? Get in touch with us! Send us an email, or post a comment here or on Facebook. You can also tweet us.

__________

How to cite this blog post (Harvard style):

Griffiths, M. (2014) Detention, Deportation, and the Family. Available at: http://bordercriminologies.law.ox.ac.uk/detention-deportation-family/ (Accessed [date]).

Share: