R (Detention Action) v SSHD: A (Partial) Victory Against Detained Fast Track

Posted:

Time to read:

Guest post by Celia Rooney, currently enrolled in the Graduate Diploma in Law at City University, a member of Lincoln’s Inn at Court, and an alumna of the University of Glasgow and the University of Oxford BCL.

This week, the High Court handed down its judgment in R (Detention Action) v Secretary of State for the Home Department. In what has been hailed as a victory for the refugee community, the court held that the detained fast track programme for dealing with asylum applications, as currently operated, is unlawful.

What is detained fast track?

Until 2008, selection for the fast track procedure was largely based on the country of origin of the applicant. However, this has since been replaced with a presumption that the vast majority of claims will be eligible for fast track. There are explicit exclusions only for those deemed to be particularly vulnerable; namely, pregnant women, the mentally ill, families with young children, and victims of torture. The test remains whether or not the Home Office believes that a quick decision can be made in the case.

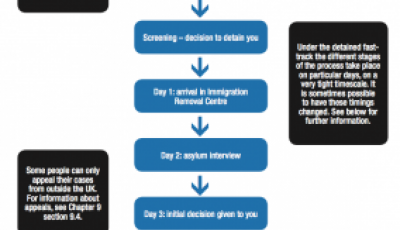

The procedure begins with an initial screening of each applicant. Decisions as to which track s/he will encounter are made at this stage. The initial screening is based on a series of basic factual questions, rather than an examination of the substance of each individual claim. This is followed by a substantive interview, after which an initial decision is made. Where the application is refused, it can be appealed to the First-Tier and Upper Tribunal.

Criticism

The process has, however, been heavily criticised by charities and international human rights agencies. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), for example, has been particularly critical of the initial screening process, highlighting that the decision to place an individual in the fast track system is too often based on speculation and factors that are irrelevant to credibility, and places too high an evidential burden on the asylum seeker. Similarly, Bail for Immigration Detainees notes the weight that is given to this first screening, despite the fact that the process ‘elicits no or virtually no information on the substance of the claim.’

Detention Action has pointed to the system’s inadequate safeguards, which fail to ensure that vulnerable applicants are excluded from the fast track process, while Human Rights Watch has adduced evidence to suggest that the system is particularly harsh on female applicants, who may initially be reluctant to disclose allegations of sexual abuse. Finally, it has been noted that although the process itself is completed extremely quickly, migrants can be in detention for several weeks before the process begins, and often remain there for a substantial period after they have exhausted all their options.

History before the courts

The fast-track system has been the subject of previous adjudication. Notably, in R (Saadi) v Secretary of State for the Home Department in 2008, the House of Lords confirmed that detention did not have to be necessary in order to be compliant with Article 5(1)f) of the European Convention on Human Rights. That provision ensures that where an individual is detained to prevent him or her making an unauthorised entry, with a view to deportation or extradition, that detention will not breach his or her right to liberty. In this regard, the court differentiated Article 5(1)f) from Article 5(1)c), which provides for detention of those suspected of committing an offence.

Campaigners have thus recognised that the judgment is only a partial victory in their fight against the fast track system. The chief executive of the Refugee Council, Maurice Wren, for example, has said that:

Today's judgment is extremely significant. However, it fails to acknowledge the reality that the detained fast track system is fundamentally unjust and can never achieve fairness. The whole purpose of the detained fast track is to condemn innocent people to a Kafkaesque procedure, solely on the say-so of Home Office officials, because it’s politically and administratively convenient to do so.

As such, while the High Court has recognised the problems of the fast track system, it has also left the door open for the government to continue operating that process by indicating how its deficiencies could be remedied. Although the judgment may lead to improved access to legal representation, it’s unlikely to alter the basic features of the fast track process. Moreover, by recognising that serious failings of that system can be remedied by access to legal advice, the court has set relatively low standards in terms of what is required to make the fast track system fair and lawful.

In bringing this legal challenge, Detention Action argued that the detained fast track procedure was no longer justified. It highlighted that it was introduced at a time when there was an unprecedented number of asylum claims and an increasing backlog, and pointed to the fact that the number of claims has fallen dramatically since 2000. In response, Mr Justice Ouseley stated that nonetheless it remains in everyone’s interests, including those of the applicants themselves, that claims are determined as quickly as possible. However, the simple logic of that statement is deceptive. The speedy determination of claims is only in the interests of refugees if it doesn’t come at the cost of fairness―a fairness that is not, and perhaps cannot, be ensured by the detained fast track procedure.

Want to start a conversation about this topic? Post a comment here or on our Facebook page. You can also tweet us.

__________

How to cite this blog post (Harvard style):

Rooney C (2014) R (Detention Action) v SSHD: A (Partial) Victory Against Detained Fast Track Available at: http://bordercriminologies.law.ox.ac.uk/detention-action-v-sshd/ (Accessed [date]).

Share: