Guest post by Karolina S. Follis. Karolina teaches in the Department of Politics, Philosophy & Religion at Lancaster University. Her research concerns the European border regime and she is the author of Building Fortress Europe: The Polish-Ukrainian Frontier.

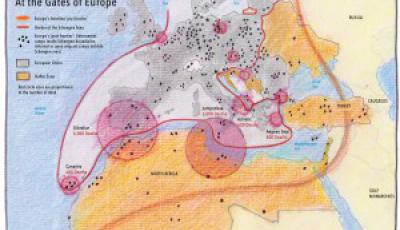

It’s winter in the Northern hemisphere, an inauspicious time for maritime journeys. And yet a place on a boat headed from North African shores towards Italy or Malta is a commodity for which traffickers can charge up to 5,000 US dollars, now or at any other time of the year. After 2013’s forty-five thousand arrivals, people have not stopped coming. Hundreds continue escaping conflict and oppressive regimes. After last autumn’s tragic shipwrecks, the EU has accelerated work on its EUROSUR programme, and Italian authorities initiated operation Mare Nostrum. Multiple successful rescues were reported in January and February. But that's not a sign of a diminishing problem. The political situation in the countries of origin is unlikely to improve anytime soon. The EU’s policy response emphasizes surveillance and control at the cost of aid and the opening of legal immigration routes. Considering these factors, the future of life at sea looks grim.

Building a picture of the situation in the Mediterranean is never a neutral process. If accurate numbers are difficult to come by, rarer still are factual accounts of particular disasters and (failed) rescue operations. One example is the 2012 report prepared by the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (PACE) rapporteur Tineke Strik on the 2011 case of the boat carrying migrants who were left to die on the way from Libya to Lampedusa. Based on interviews with the survivors, authorities, maritime rescue centers, and NGOs, as well as collaboration with academics and documentary filmmakers, the report shows how 61 of 72 passengers of the boat lost their lives after calls for help were ignored by passing aircraft and military vessels. Major daily papers drew extensively on the report’s findings, and the case became known in Europe and beyond. It became a symbol of the crisis on the Mediterranean and of the EU’s and NATO’s willful impotence in responding to it. This coming April in Strasbourg, Strik will present the results of her follow-up report on the actions and reactions to the left-to-die boat case. When they are publicized, it's worth remembering that the new findings will not be circulating in a vacuum, but in a charged space where no facts stay neutral for very long.

Want to start a conversation about this topic? Post a comment here or on our Facebook page. You can also tweet us.

__________

How to cite this blog post (Harvard style): Follis K (2014) The Politics of Life at Sea: A Note on Sources. Available at: http://bordercriminologies.law.ox.ac.uk/the-politics-of-life-at-sea (accessed [date]).

Share: