Guest post by Ingrid Eagly, Assistant Professor of Law, UCLA School of Law. Ingrid’s research examines the integration of criminal and immigration enforcement. In addition to the article cited in the piece below, other recent work examines the potential expansion of the right to appointed immigration counsel for noncitizens, particularly those held in detention. Her current project explores the significance of increased reliance on videoconferencing, rather than in-person appearances, to adjudicate the immigration cases of detained immigrants.

How are local criminal justice systems structured in an era of immigration policing? In a forthcoming article, I explore this question by examining how local criminal justice participants in the United States go about their day-to-day work. How are the programs, priorities, and procedures of immigration deportation integrated into the institutional structure of local criminal justice agencies? How do immigration-oriented concerns (such as deportation and migration control) interact at the local level with criminal justice-oriented concerns (such as criminal punishment and crime control)?

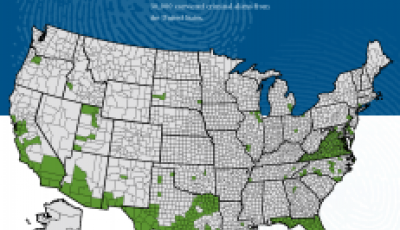

In order to understand the development of the criminal-immigration enforcement nexus, over the past three years I studied the criminal justice systems in three of the largest urban centers in the United States: Los Angeles County, California; Harris County, Texas; and Maricopa County, Arizona. I selected these three counties because each ranks among the top in the nation on various indices of immigration enforcement, including the number of fingerprint matches found through the federal government’s new jail-based immigration screening program known as Secure Communities. This steady flow of noncitizens is perhaps not surprising given that these southwestern counties are among the most populous in the nation and manage massive criminal caseloads. Each county is also located close to the Mexican border and has a significant noncitizen population. The geography and demographics of these three jurisdictions thus afford them significant experience with the criminal processing of noncitizens.

To document local practices, I conducted interviews with stakeholders in the three counties—prosecutors, public defenders, private attorneys, judges, pretrial services officers, probation officers, and jail personnel. I also gathered other relevant data, including local laws and procedures, criminal court documents and forms, criminal and immigration enforcement statistics, and prosecution policies and training materials.

My research on these three counties reveals two important findings. First, criminal law’s integration with immigration enforcement has a far more powerful impact on local criminal process than previously understood. Across all three counties, criminal law officials are keenly aware of both the immigration status of defendants and the practical effects of the federal government’s reliance on convictions in making immigration enforcement decisions. Federal immigration agents are a continuous presence in the local law enforcement system: They are often physically present in local jails, impede release on criminal bail, train prosecutors on how to secure plea agreements that guarantee removal, and sometimes deport noncitizen defendants prior to their criminal trials. Deportation also poses unique challenges for plea bargaining and sentencing because noncitizens are often deported before they are able to complete probation, community service, or other similar requirements imposed by the criminal court.

Second, despite these consistently deep connections between federal and local officials across all three counties, each county has navigated this criminal-immigration integration in a strikingly different way. At the county level, criminal justice for noncitizens is influenced by two sets of discretionary decisions: local practices that weigh alienage status at different points in the criminal process (such as enhancing a criminal sentence if a defendant is undocumented) and criminal policies and procedures adopted in response to federal immigration enforcement efforts (such as reporting arrestees to immigration authorities or fashioning a plea agreement to avoid deportation). In each county, the various criminal system participants (including prosecutors, defense attorneys, judges, and probation officers) have developed a shared understanding of the local criminal system’s role in both sets of discretionary decisions.

Los Angeles has adopted an alienage neutral model that seeks to shield the criminal process from consideration of immigration status and the disproportionate effects of immigration enforcement on criminal bargaining and sentencing outcomes. Harris County has implemented an illegal alien punishment model in which judges and prosecutors allocate harsher criminal system punishments for those who commit crimes while in violation of this country’s immigration laws. Finally, Maricopa County has created an immigration enforcement model in which local law enforcement, prosecutors, judges, and probation officers attempt to discern immigration status at every stage in the criminal process and bring all potentially deportable noncitizens to the attention of federal immigration officials.

For the criminal justice system, the three counties teach us that localities have quite different approaches to the two central issues in noncitizen criminal justice: (1) how to allocate criminal sanctions across citizens and noncitizens and (2) the proper involvement of crime control in immigration. Disentangling these two issues makes it possible to entertain with more clarity the practical effects of criminal justice policies and practices for noncitizens, and to apply this understanding to other criminal jurisdictions. For the immigration system, the county models of noncitizen criminal justice challenge the standard assumption of national uniformity that drives much of United States immigration policy. If uniformity is indeed the desired federal approach, more careful thought must be applied in two important areas: (1) the exercise of discretion in making deportation decisions and (2) the federal supervision of local criminal justice practices.

Want to start a discussion about this topic? Post a comment here or on our Facebook page. You can also tweet us.

__________

How to cite this blog post (Harvard style):

Eagly L (2013) Criminal Justice for Noncitizens: Variation in US Local Enforcement. Available at: http://bordercriminologies.law.ox.ac.uk/criminal-justice-for-noncitizens/ (Accessed [date]).

Share: