Earlier this year, the Open Data Institute (ODI) published research looking at the viability of data trusts, and it defined such a trust as a ‘legal structure that provides independent stewardship of data’. The research was funded by the UK Government, and exploring such trusts is a key part of the infrastructure strand of its AI Sector Deal. The ODI reported “huge demand from private, public and third sector organisations in countries around the world to explore data trusts”: in 2018, for example, Sidewalk Labs, as part of its work in developing a “smart city” in part of Toronto, proposed using a “Civic Data Trust” as a means of meeting fears as to data privacy.

Last month, the Alan Turing Institute, in collaboration with the Jesus College Intellectual Forum, organised a workshop on Data Trusts, with participants from many different organisations, and I gave a keynote talk on ‘Trust Law 101’. A particular issue to confront was the suggestion, made in a report commissioned by the ODI, that, as data is not property, it cannot be the subject matter of a valid trust, and so a data trust could only be legally valid if there were a “redefinition of trust property so as to include data”. That suggestion has recently been challenged by Delacroix and Lawrence, as well as by Lau, Penner and Wong, and I argued that rejecting it is not only practically important (given the great interest in data trusts) but also conceptually justified.

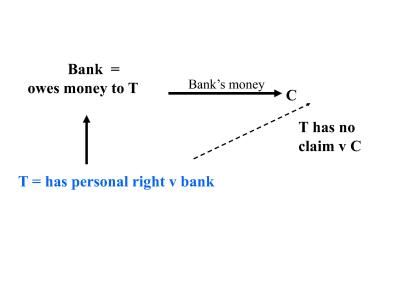

The key point is that we have to be very careful about the different contexts in which the term ‘property’ is used. ‘Property’ is of course a very useful and powerful concept, but it is used to help answer a number of different legal questions. So the fact that data does not count as ‘property’ for one context does not mean that it cannot be ‘property’ for another, different context. We can see this by considering, for example, a simple contractual right, such as B’s right, arising under a contract with A, to be paid £100 by A. Does such a right count as ‘property’? It all depends on the context. If ‘property’ is used to mean ‘something held by B, so that if X interferes with that thing, X will be strictly liable to B’ then the answer , given by the majority of the House of Lords in OBG v Allan, is No. If ‘property’ is used to mean ‘something held by B, that is capable of being held by B on trust for another’ then the answer is Yes. As Briggs J (now Lord Briggs) pointed out, at [241] in re Lehman Bros International (Europe), it is perfectly common for such personal contractual rights to be held on trust, as occurs with a solicitor’s client account: the bank account is a personal right held by the solicitor against the bank, and it is held by the solicitor on trust for the clients. As can be seen in the accompanying diagram (Figure 1), if the bank transfers money to a third party, the holder of the account (the trustee) has no claim against such a third party, as the holder has no right in relation to any particular assets held by the bank. In contrast, the beneficiary (B) of the trust does have a right in relation to a particular asset: the bank account. B can thus be seen as having a right against, or in relation to, the right held by the trustee (T).

This means that case-law holding, for example, that data does not count as ‘property’ and so no action in conversion is available to B if X interferes with B’s data does not, in itself, mean that data cannot be held on trust. This should not be surprising: the type of considerations which are relevant in deciding if X should be strictly liable for interfering with something (e.g. how great a practical limit would that impose on X’s freedom of action?) are different from those that matter when asking if something can be held on trust. In fact, when we look at how courts have answered the question of what can be held on trust, the main requirement is that the trust must relate to a specific right held by the trustee. We have already seen that a simple contractual right, like a bank account, can be held on trust; the English courts have also found that a non-assignable contractual right can be held on trust. This fits with a model of trusts law which emphasizes that it is not simply a branch of property law; it is rather concerned with situations where equity recognises that a party (the trustee) holds a right, but is under duties to another (the beneficiary) in relation to that right.

There may however be some limits as to which rights can be held on trust. In an article written with my colleague Robert Stevens, we suggested, for example, that if B’s right is purely negative (i.e. it consists simply of A not being under a duty to B, or of A not having a power to change B’s legal position) then it cannot be held on trust. An example would be what Hohfeld calls a ‘liberty’ of B: so I have a liberty against you to walk down the street, as I have no duty to you not to do so. It is difficult to see how such an essentially negative right could be held on trust.

This means that in deciding what sort of data can be held on trust, we should move away from the unhelpful question of ‘is it property?’ and instead look more carefully at the precise type of rights of which the particular data consist. So if the right in question is a contractual right against a particular party to have access to a database, there would seem to be no difficulty in such a right being the subject matter of a trust. An interesting question arises in relation to rights under the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR): to the extent that those rights are correlatives of duties owed by data controllers, they should be capable of being held on trust. If (and it is a big ‘if’) those rights can be assigned to a trustee, this opens up the possibility of the rights of many data subjects being held by a trustee, with such a trustee having the power to assert such rights collectively and thus to bargain more effectively with a data controller – an analogy can be draw to the role of bond trustees.

Data trusts touch on further aspects of trusts law – for example, where the aim is that trustees can use data only to advance a specific purpose, then in English law a data trust can work only if the purpose counts as a charitable one. If not, there is then the possibility of establishing a non-charitable purpose trust governed by the law of a jurisdiction which does permit private purpose trusts (such as e.g. the Cayman Islands) and invoking the Hague Trusts Convention (by means of the Recognition of Trusts Act 1987) to ensure that an English court recognises such a trust. Some of those issues are touched on in the accompanying set of slides.

To conclude, it is perhaps worth pulling back from data trusts to consider some broader ideas. First, there is the danger of transferring findings about whether something is or is not property from one context to another. In a forthcoming article in the Oxford Journal of Legal Studies, colleague Simon Douglas and I discuss the danger of the argument: “This is property, therefore…”. The problematic argument in relation to data trusts is the converse one: “This is not property, therefore…”. Second, one of the advantages of a flexible, ‘bottom-up’ system such as the common law may be precisely that we do not have to make a final and overall decision as to whether a particular type of right is or is not property. Finally, that flexibility is enhanced by equitable concepts, such as the trust, which have continually adapted to meet new commercial and technological demands. Taking into account the long history of the trust, we should be confident that it can rise to the challenge of handling data. After all, as Maitland famously noted, perhaps the “greatest and most distinctive achievement” of English law is the “development from century to century of the trust idea.”

How to cite this blog post (Harvard style)

McFarlane, B. (2019). Data Trusts and Defining Property. Available at https://www.law.ox.ac.uk/research-and-subject-groups/property-law/blog/2019/10/data-trusts-and-defining-property (Accessed [date])

Share: