Law and finance scholars have long found corporate law largely irrelevant for startups and venture capital (VC): since founders and investors often ‘contract around’ mandatory rules, legal differences are negligible. Yet this assumption sits uneasily with persistent empirical patterns. Most VC-backed startups in the United States incorporate in Delaware—not for tax or hiring reasons, but to be governed by Delaware corporate law, which is widely viewed as more enabling. Growing comparative evidence also shows that rigid corporate law rules hamper US-style deals in other jurisdictions (e.g., Enriques, Nigro & Tröger 2025; Lee 2024; Andrade 2024; Lin 2020; Giudici & Agstner, 2019; Shishido 2014). If corporate law matters, has it adapted to the needs of founders and VC investors?

In a recent article, I introduce two novel empirical measures—a 20-year, 12-country legal index and an international dataset of billion-dollar ‘unicorn’ startups—and find that corporate law has evolved to facilitate startup contracting, but only selectively. Politically easier reforms, such as authorizing multiple-vote shares, have proliferated, while core governance constraints remain largely untouched. These persistent rigidities help explain why some founders choose to incorporate abroad (what I term ‘Founder Drain’) and why international VCs condition financing on multi-jurisdictional structures to avoid domestic law (what I term ‘Offshore Governance’). Within countries, selective flexibility shapes incorporation choices, influences ‘unicorn’ formation, and deepens governance risks in private markets.

Beyond Contracts: The Startup Corporate Law Index

Financing startups is difficult. It requires ambitious founders to reveal their ideas—their main asset—and investors to commit capital over time despite deep uncertainty about outcomes. VCs have developed an array of contractual solutions to address these challenges and mitigate the risks they create (Kaplan & Strömberg 2003). Yet even the most sophisticated contracts govern rights within a startup company. Thus, as I show in earlier work, founder–investor deals are ultimately constrained by the corporate law rules governing private companies’ boards, shares, and shareholders’ agreements—what I term Startup Corporate Law (SCL).

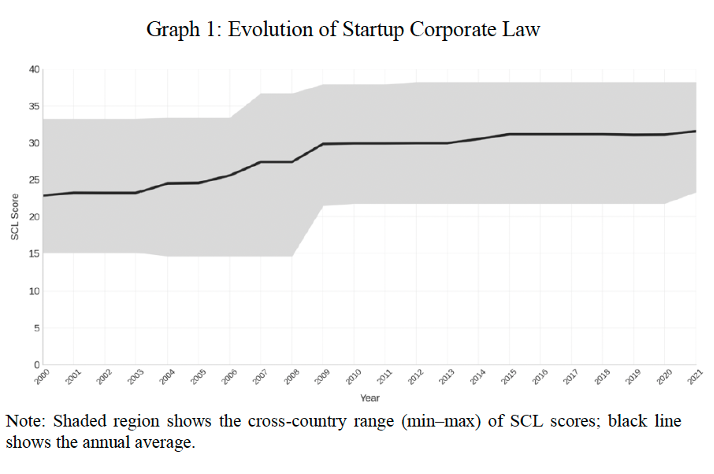

To examine how these rules have evolved, I developed the SCL Index, a 20-year, 12-country measure of the core legal rules that frame founder-investor bargains. The Index tracks changes in three areas—board structure and powers, shareclasses and rights, and the scope and enforceability of shareholders’ agreements—and assigns higher scores where parties are legally free to design their own arrangements. Unlike widely used measures in VC research, such as the anti-director rights index (ADRI) and the anti-self-dealing index (ASDI), the SCL Index captures the rules that actually matter for early-stage financing and offers the first time-series account of how these rules have changed across jurisdictions.

Main Findings

1. Corporate Laws Are Not Uniformly Enabling

The first finding is straightforward: SCL was far more rigid in the early 2000s than commonly assumed. For example, caps on the number of votes per share and mandatory rules that restricted how boards could be structured limited the universe of founder-investor bargains. These findings challenge the pervasive assumption that private companies are governed by enabling laws across jurisdictions and invite further scrutiny in economies aiming to promote VC through legal reform.

2. Flexibility Is Increasing—but Selectively

The SCL Index also reveals that corporate laws have evolved through a process of ‘selective flexibility’, in which certain legal barriers to VC deals have been lifted, while others are stealthily preserved. For example, most jurisdictions have expanded the number of votes per share, but far fewer have amended rules governing board powers or shareholders’ agreements. The result is an uneven landscape in which headline reforms create an appearance of flexibility as deeper governance constraints persist. Notably, these trends unfolded largely independently of broader economic integration efforts, like the European Union. In fact, even within economic blocs, startup-driven reforms target different legal entities, some of which are poorly suited for high-growth finance.

3. Unicorn Formation

Using a new dataset of unicorns founded by entrepreneurs from the twelve indexed jurisdictions, the study examines how changes in SCL relate to startup growth and uncovers two patterns. First, Europe’s strongest innovation hubs produce unicorns despite only modest improvements in SCL, a sign that robust ecosystems can compensate for rigid law—but also that these economies may be underperforming their potential. Second, no unicorn appears below an approximate SCL threshold, and unicorn formation increased sharply in the Netherlands after a major reform raised its SCL score. In tandem, these trends indicate that more flexible corporate law can help create the conditions for high-growth firms to emerge.

4. Founder Drain and Offshore Governance

The analysis on Founder Drain—when entrepreneurs relocate abroad before starting their companies—shows a clear continental divide. In Latin America, the data reveal more Latin American unicorn founders building their companies at home than in the US, suggesting that recent improvements in SCL have helped retain high-impact entrepreneurs. In Europe, the pattern reverses: countries with historically rigid SCL—e.g., Poland, Portugal, and Russia—have more unicorn founders starting companies in the US than domestically. This divergence underscores a central insight of the study: corporate law influences where ambitious founders launch and scale their businesses, and rigid SCL frameworks can push entrepreneurial talent abroad even in otherwise promising markets.

As for Offshore Governance—the investor-driven practice of shifting a startup’s capital and governance structure to a foreign parent—the analysis reveals a similar divide. In Latin America, most unicorns adopt offshore structures (typically with a Delaware or Cayman Islands parent), reflecting investors’ concerns around legal uncertainty and enforcement. In Europe, the opposite holds: most unicorns rely on domestic rather than offshore structures for fundraising, suggesting that stronger legal and market institutions reduce the need for external legal protections. A notable exception is Portugal, whose sole unicorn was financed through an offshore parent, highlighting that rigid SCL can discourage direct investment even in trusted legal systems.

These two previously unrecognized dynamics have implications that reach far beyond individual deals. Together, they can slow market and institutional development, depriving domestic markets of the spillovers that thriving startup ecosystems typically generate.

5. Corporate Law and Governance

Selective flexibility also has implications for corporate law and governance. Delaware’s expansive private ordering regime has supported the growth of VC but has also generated new governance challenges (see, e.g., Talley and Sanga 2023; Fisch 2022; Aran 2019; Pollman 2019). The SCL Index suggests that some of these challenges—such as ambiguous fiduciary duties for investor-appointed directors and increasing risks for employees with stock-based compensation—are less likely to arise in the indexed jurisdictions because board powers remain more limited. Other challenges, however, are quietly emerging. For example, new agency problems stemming from differentiated share classes and shadow governance structures arranged through private shareholders’ agreements, which have seldom been regulated or enforced.

Implications

These findings carry implications for different audiences:

- Financial economists: The SCL Index offers a fresh and more accurate measure of legal quality for empirical VC research.

- Corporate law scholars: Selective flexibility reveals new governance risks that warrant closer examination.

- Practitioners and founders: Jurisdictional differences in SCL inform incorporation choices and investor expectations. Understanding these differences is increasingly critical to designing scalable governance arrangements.

- Policymakers: Reforms should go beyond expanding voting rights and confront the deeper legal determinants of founder–investor bargains, as well as the tradeoffs embedded in different legal architectures.

Conclusion

Corporate law matters for startups and VC. Not because it determines outcomes, but because it defines the legal space in which founders and investors structure the finance and governance of high-growth firms. The SCL Index reveals that this space has quietly expanded over the past two decades, yet only in selective ways that leave important constraints in place. Future reforms must recognize that greater flexibility brings greater governance risks. Flexibility should be deliberate and calibrated—not incidental.

The full article can be found here.

Alvaro Pereira is an Assistant Professor of Law at Georgia State University.

OBLB types:

OBLB keywords:

Jurisdiction:

Share: