Film Review: “To a Land Unknown”

Posted

Time to read

Guest post by Dr Emma Patchett. Emma is a Lecturer in Law at Northumbria University. Her current research explores border crossings in law, literature and film. She reviews this film in advance of the London Migration Film Festival 2024. The festival aims to portray the diversity and humanity of migration. ‘To a Land Unknown’ will be screened on the 25th of November (6:30pm) at Genesis Cinema as part of the London Migration Film Festival 2024.

Review of To a Land Unknown (Dir: Mahdi Fleifel, 2024)

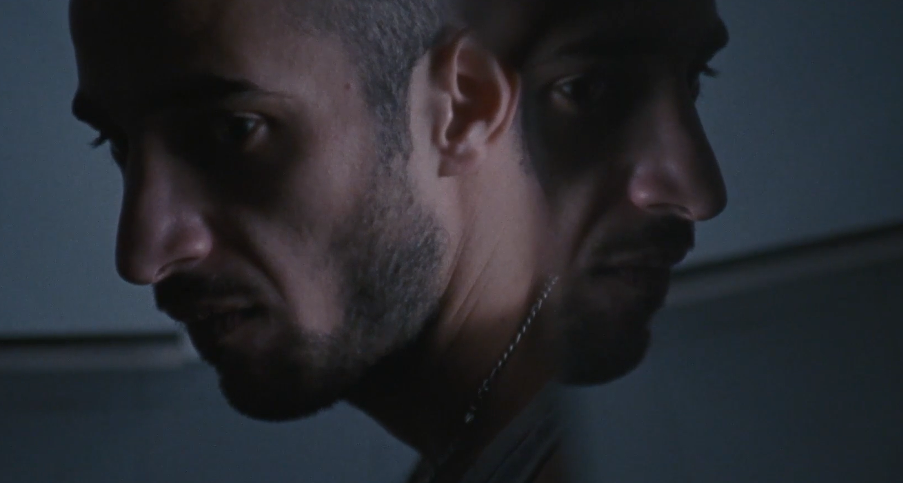

To a Land Unknown is a snapshot in the lives of two Palestinian refugees, Chatila (Mahmood Bakri) and Reda (Aram Sabbah), unhappily marooned in Athens as they attempt to find ways to source funds to secure a route to Germany. Thodoris Mihopoulos’ exquisitely picturesque and naturalistic cinematography is set against a haunting soundtrack which perfectly captures the jarring discombobulation of place for those subject to the migration regime.

Reda and Chatila are cousins navigating the seedy underbelly of Athens – they steal money to pay Marwan (Mondher Rayahneh), who is helping them procure fake documents for their escape, with the heroin-addicted Reda also engaging in sex work in a local park. They meet Malik (Mohammad Alsurafa), a young Palestinian boy from Gaza who has been stranded on his own, and decide to cut out the middleman by helping him get to Italy in the company of Tatiana (Angeliki Papoulia), a lonely Greek woman Chatila befriends. The film does not romanticise the refugee experience, nor shy away from the complex morality of practices of smuggling and criminality, reflecting perhaps Fleifel’s aim to make engaging narrative films which are “honest” about the human experience: “we're not always pure."

The audience witness the two lead characters navigating the city as a complex urban maze, or a carceral space: money is hidden behind walls, the camera zooms in to close-ups in claustrophobic shared living quarters. We track Reda and Chatila as they walk purposefully through the city streets as the light fades, against a backdrop of walls adorned with graffiti. Fleifel describes it as “being stranded in a purgatory, trying to make it to Northern Europe”.

Yet, paradoxically, this is also an open space – the two men are silhouetted against the dusk, the lights of Athens far beneath them, with wide shots capturing the city skyline, and low angle shots looking at the moon up above. Despite being trapped in Athens the men are not passive subjects of the migration regime, as Reda tells Chatila, “you were broke, unemployed, you begged me to come to Europe!”. Indeed, it is clear this is a return journey for Reda. When asked why he left Lebanon he says, “it is not our country”, stating that “Lebanon is a prison, like Gaza”. The film director Fleifel refers to Athens as an “urban desert”, reminiscent of the Kuwaiti desert in Ghassan Kanafani’s novel Men in the Sun in which Palestinian refugees end up stranded in the desert after leaving their refugee camp to find work. Indeed, Greece, which Reda calls simply a temporary “layover” in the film, is often described as the ‘gateway’ to Europe for many refugees and migrants. According to the UNHCR, a total of 52,571 refugees and migrants have arrived in Greece during 2024.

And yet, it is not simply framed as an empty site of transit in this film. The courtyard becomes part of what Charalampos Tsavdaroglou and Maria Kaika might define as a “commoning practice” in which buildings or squats are occupied in the centre of Athens – as opposed to being relegated to refugee camps in the margins of the city – reflecting forms of solidarity and heterogenous acts of resistance.

Just as Fleifel’s thriller subverts the notion of inhabitation, it also plays with the theme of temporality at the site of the insidious border. Although the plot centres on a few days in the lives of the two main characters attempting to get enough money to buy passports, there are tendrils connecting them to multiple ‘elsewheres’ – Chatila speaks to his wife and two-year-old son on the phone, stuck in a camp in Lebanon. They often speak about the café they intend to run in Germany, and wistfully recall a local café that was once the centre of the community ‘back home’. The men they intend to smuggle over the border talk about their journey to Greece – “we nearly drowned” – and the ‘password’ for safe passage is “Long Live Syria!”. Although the film takes place in Athens, border crossings therefore loom large in the background. Whilst ruefully lamenting the fact they have to find money for papers, they reflect that “at least we aren’t fucked trying to cross the borders on foot” or “suffocating in the back of a truck”.

Many of the stories of the characters we meet are left untold; the final shot is of Reda and Chatila in tragic circumstances at the back of the bus, what will come next in Chatila’s ongoing journey unknown. This sense of unfinished stories echoes the experience of Palestinian refugees, which is often one of displacement, dispossession and the denial of history (see, for example, the work of Yafa El Masri, Are Knudsen and Sari Hanafi, Elena Fiddian-Qasmiyeh, and Ghada Karmi) and never more so than now, at a time of crisis and destruction in both Palestine and Lebanon.

As a result of ongoing suffering and displacement, as Tahrir Hamdi observes, there is a need for a range of counter-narratives as a form of resistance. Before becoming a Danish resident, the director Mahdi Fleifel spent his early years in Ein El-Hilweh, a Palestinian refugee camp in South Lebanon. It is clear, however, that Fleifel doesn’t only want his work to be understood as a singular commentary on Palestinian resistance alone – for him, "this is a film made in exile about exiles and for exiles, whoever doesn't feel like they belong in this world of ours today”.

To a Land Unknown raises intriguing questions about the concept of outsiderness, struggle and survival at a time when, rather than creating safe routes for example, public and political discourse often centres on the desire to criminalise those profiting from border crossings. The film’s powerful depiction of flawed central characters moving through the carceral city in the hope of reaching an ‘elsewhere’ through scamming, stealing and cheating is simultaneously a reflection of academic scholarship which problematises narratives of Palestinian refugees solely as symbols of resistance, rather than having to engage in practices of daily struggle with their material conditions. In one scene, the drug dealer Abu Love (Mouataz Alshalton) is reciting the seminal epic poem ‘In Praise of the High Shadow’ by the Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish as the camera pans across the room: “You will either have to be/Or you will not be…the mask/Has fallen, and there’s no one/None but you in this stretch of space/Open to enemies and forgetfulness”. Darwish’s reflection on the dislocation of exile, audible as a soundtrack to the slow pan across the faces of the men waiting in the room, is simultaneously a form of resistance, and demands a new way of thinking about identity and belonging in purgatorial space.

Any comments about this post? Get in touch with us! Send us an email, or post a comment here or on Facebook. You can also tweet us.

How to cite this blog post (Harvard style):

E. Patchett. (2024) Film Review: “To a Land Unknown” . Available at:https://blogs.law.ox.ac.uk/border-criminologies-blog/blog-post/2024/11/film-review-land-unknown. Accessed on: 21/11/2024Share

YOU MAY ALSO BE INTERESTED IN

With the support of