How can we design and conduct research that explores the relationship between ethnicity and crime? And how can this be carried out comprehensively, ethically and sensitively? How can research on ethnicity and crime avoid perpetuating criminalizing stereotypes and being complicit in reproducing essentialized representations of minority ethnic groups and ‘othering’ them? In the following piece I draw on my experiences on conducting empirical research on British Asian communities and perceptions of crime and the criminalization of British Asian and Black youth.

Trying to represent the group you are researching in a conceptually meaningful way is central to ‘good’ research in this field. Criminology has long been criticised for its inaccurate representation of diversity, for example, the heterogeneity of minority ethnic groups is often masked by the representation of these groups (Asian, Black, White) as being the same internally (Hudson 2008). Criminological statistics and research too often use the term ‘Asian’ thereby obscuring any differences between British Pakistanis, British Bangladeshis and British Indians. Although there may be shared political struggles amongst these groups, the conflation of nationality, language, geography, religion and a vast array of histories into easy categories such as ‘Asian’ or ‘Black’ can present an inaccurate reflection of the different experiences of members belonging to these groups and perpetuate stereotypes and myths of sameness based on physical attributes. Ethnic boundaries are often presented as concrete rather than porous and mixedness is rarely considered in any detail.

A close understanding of the history of race and racism and the concepts of ethnicity and postcoloniality are important and can inform the ways in which research questions are crafted, framed and asked. For example, scholarship within Sociology, Ethnic and Racial Studies and English Literature has critically examined the fluidity and mutability of ethnicities as well as other representations of Black and Asian Masculinities which are able to provide key insights to the issues that criminologists address. Human geography has shown how minority groups may perceive their neighbourhoods differently and how experiences of racism can shape such perceptions (Amin 2003). Crossing disciplinary boundaries opens up a rich resource that can furnish your research design and collation with a critical lens and provide a depth to the interpretation and analysis of your findings. Although first time researchers may consider this a hostage to fortune, crossing into different disciplines has been valuable and transformative for my own research frames and methodological design – I have integrated sociological concepts of conviviality, diaspora and cosmopolitanism into my work, adopted a deconstructionist lens and combined it with my empirical findings and learned about how processes of Orientalism and Occidentalism continue to reproduce and fix cultural representations of ‘others’ in society.

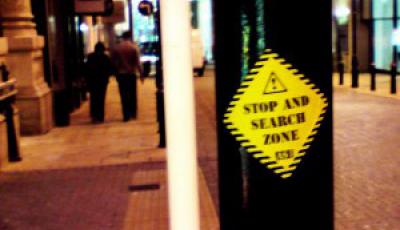

Criminological research on racism and ethnicity has also tended to focus on making comparisons between ethnic groups (e.g. the experience of black offenders and white offenders, black victims and Asian victims) and although this is important work, the binary logic of difference, which dissolves diversity into these differences, is perhaps something that criminologists should look beyond (Hudson 2003). As socio-political concerns for countering terrorism, controlling migrants, violence amongst Black and Asian groups continue to intensify, criminological responses need to perhaps engage more meaningfully and more reflectively with diversity, structural racism and the lived realities of multi-ethnic living in contemporary society.

Keywords:

(Field) Research and Methods

Share: