Insights from the Early Establishment of Banking Supervision in Italy (1926-1936)

Posted:

Time to read:

Appropriate regulation is usually regarded as key to ensure financial stability. For the law not to remain ‘on paper’, proper rule enforcement is required through effective supervision. What are the challenges that supervision authorities face in their day-to-day work? Research on how supervision authorities operate is hindered by the lack of available data and information. Finance being an industry where confidence is crucial, supervisory authorities cannot share information and data with academics, as this would constitute a breach of the confidentiality so vital for its smooth operation. One discipline, however, might provide insight: history, the only ‘laboratory’ available to social scientists.

In a recent paper, we discuss the enactment of the first Italian commercial banking regulation in 1926 to shed light on the operation of banking supervision. To do so, we study previously classified documents from the historical archives of the Bank of Italy (BoI).

Comparing the first draft with the final version reveals that the law went through a substantial watering-down, which can be attributed to lobbying pressure by the Italian Banking Association (ABI). ABI had strongly opposed the first draft’s arrangement whereby the Ministry of Finance was the enforcer of the law: in the final version, the BoI was put in charge of both contact and off-site supervision. Liquidity provisions were scrapped, while capital requirements and risk concentration measures attenuated. One of the few strengthening elements of the final law was a more explicit definition of the authority’s powers during contact supervision: when inspected, banks had the ‘obligation to produce all documents to the officials required for the exercise of their powers’.

The appointment of the BoI as supervisor was remarkable for the time. It became the first European central bank to actively perform inspections. This was not uncontroversial, since at those times it still performed commercial banking activity — thus, it was a direct competitor of other credit institutions. This appointment, however, did not just bring conflicts of interest, but also important synergies. The operation of banking supervision was highly decentralised: the directors of the BoI’s local branches were in charge of supervision. The rationale was explicitly to exploit their detailed knowledge of local markets, which a centralised body of inspectors built from scratch could have never had. Furthermore, we find that in performing lending of last resort to distressed banks, the BoI employed the information acquired through its supervision activity to discern insolvent banks from illiquid ones deserving assistance.

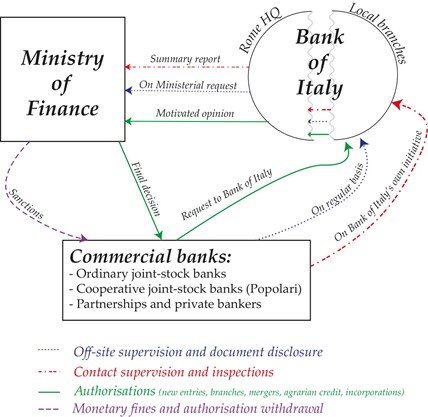

Figure 1 summarises the supervision framework under the 1926 law. The Ministry of Finance retained the power to issue authorisations and fines, but technical advice was provided by the BoI. Full inspection reports were prepared for the BoI’s Governor. The Governor or the Vice-Director General (Head of Supervision) then prepared a summary for the Minister of Finance — when appropriate, with a list of the wrongdoings and the BoI’s requests to the inspected bank. Throughout the period, local branches — especially in cities with many banks — lamented scarcity of qualified personnel to dedicate to supervision activities.

Figure 1. Supervision framework for Italian commercial banks under 1926 banking law

In the early years, multiple conflicts arose between the supervisor and the supervisees, many being due to loopholes in the law. Banks tried to appeal to the ‘letter’ of the law to avoid abiding by the request of the supervisor. But the BoI was adamant, invoking the ‘spirit’ of the law and/or recurring to analogies with the Code of Commerce then in force to justify provisions on which the law was ambiguous or silent. Comparing the original law with the provisions actually enforced in the 1930s, it is undeniable that the prerogatives of the BoI had been sensibly expanded. This process did not happen through coercion, but moral suasion. In part, moral suasion was effective thanks to the prestige that the BoI exerted in the Italian financial system, but not only. A growing dialogue with ABI (and the Ministry of Finance) created a fruitful cooperation environment. This was openly recognised by banks and confirmed by BoI internal reports.

This cooperative environment, however, was also achieved by means that could be regarded as controversial. The BoI and the Ministry of Finance ensured full cooperation of banks regarding the disclosure of information vital for financial stability, but this was obtained at the expense of fiscal compliance. Bank secrecy was guaranteed and banks were assured that under no circumstances the information on their clients acquired through supervision could be shared with fiscal authorities. Remarkably, the office at the Ministry of Finance that dealt with banking supervision would not pass the information to the tax authorities. Another issue was the trade-off between disclosure of information to the public and supervisors. Even before 1926, banks had to disclose their reports to the public using very detailed standardised forms. However, since these were not verified, banks could manipulate them — eg not declaring ‘bad loans’, or hiding tax relevant deposits under different categories. In 1929, new and more accurate public forms were introduced. However, these were much less detailed and responding to the ‘need of not disclosing information that it is inconvenient to disclose’. In parallel, reserved and very detailed forms were introduced for supervisory purposes.

The experience of Italy shows that, unsurprisingly, banking supervision is intrinsically a complex matter, with conflicting issues arising in parallel. In times of crises, such were the 1930s, supervision authorities favoured the development of a cooperative environment with banks which, thanks to compliance and smooth information disclosure, eased the BoI’s mandate to preserve financial stability. Our research also points out that, while regulation and supervision are sometimes used as synonyms, the way rules are enforced matters no less than the very letter of the law. Cooperation between supervisor and supervisee is crucial, and, as the case of interwar Italy shows, it often comes at a cost.

Marco Molteni is a Postdoctoral Researcher at the Faculty of History, University of Oxford.

Dario Pellegrino is an Economist at the Bank of Italy.

The views expressed in this piece are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Bank of Italy.

Share: