Since the early 1990s, there has been rough gender parity in terms of attendance at law school and entry into the top law firms. But what happens afterwards? What is the gender gap, if any, in progress toward leadership roles? The research on law firms thus far has largely focused on the achievement of partnership status. We know from that research that there is significant attrition between entry into the firms and the attainment of partner status—with women making up only 20-25 percent of the equity partners. Achieving partnership though is like making it into the main draw at Wimbledon. It requires enormous effort and is an accomplishment in itself. However, it is but the entry ticket to the real tournament, to working with the most important clients in a leadership position. The question we ask in our new paper, ‘Gender, Credentials and M&A’, is whether there is a gender gap in who wins the tournament in the world of high powered mergers and acquisitions deals. That is, what is the gender gap for who wins the tournament?

The question of whether there is a widening (or narrowing) of the gender gap between entry into the main draw (we can roughly conceptualize this as making partner) and winning is interesting to us for a couple of reasons.

First, one of the standard explanations for why there are gender gaps in high level jobs is that women opt out from the competition early—the assumption being that they usually have greater care responsibilities than their male counterparts. If that is the primary explanation though, that means that we should not see a widening of the gender gap in those settings where we can be confident that the women in the tournament are competing just as hard as the men and are similarly situated (roughly, when they are all at the equity partner stage).

Second, research by scholars such as Claudia Goldin suggests that the gender gap is wider in ‘greedy work’ contexts. In these settings, employees have very little flexibility—that is, they have to be ready to drop everything in their personal lives and turn to work at a moment’s notice. M&A deal leadership, perhaps more than any other practice area at the major law firms, fits the model of a greedy work setting where the senior lawyers have to be ready to jump on a plane to Tokyo at a moment’s notice if the clients wants that. And that makes M&A deal leadership a particularly interesting setting in which to study the gender gap.

To examine the question of who makes it to the top of M&A deals, we construct a dataset using all of the merger agreements publicly filed with the US Securities and Exchange Commission over an 11 year period—2010-20. These documents, in their notice provisions, typically report who the lead lawyers on the deals were. This designation, as conversations with M&A lawyers told us, does not mean that the lawyer in question necessarily did the most or best work on the deal. In other words, it is not a measure of lawyering quality (which, we confess, was our initial thought—but practitioners quickly disabused us of that notion). Instead, those designated as deal leaders are likely the lawyer at the firm with the thickest relationship with the client; the ‘relationship partner’ in the patois of the profession. And this person typically gets paid more when it comes bonus time, since they are the one maintaining the relationship with the client from where all the others on the team receive billable hours.

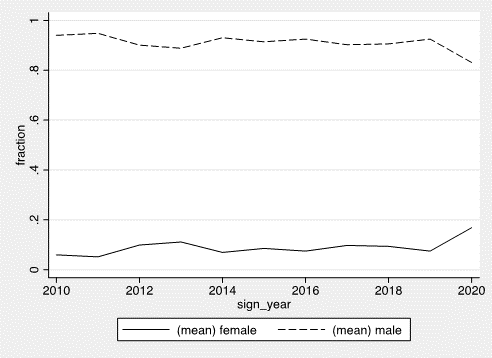

So, what do we find in terms of who makes relationship partner? As Figure 4 from our article (reproduced below) shows, women consistently only make up somewhere around 9 to 10 percent of the deal leaders for the decade for which we collected data. Controlling for their rates of partnership, women are much less likely to lead deals than men. Their roughly 10 percent representation shows no indication of any upward trend over the decade for which we have data—except intriguingly in the very last year of our dataset (when covid-19 hit).

Figure 4: Lawyers Chosen to Lead M&A Deal; Gender Composition, 2010-2020

Among the universe of M&A lawyers, the ones chosen to lead a deal are disproportionately partners and have attended elite law schools, often excelling (eg, Order of the Coif). Women are less likely to be chosen from this pool, even when attending elite law schools and are partners at their respective firms.

When we look just at the universe of lawyers leading the deal, we see that where one went to law school and what honors one acquired matter for both men and women M&A partners. But here is the rub: They matter considerably more for women than men. And one credential—attending an elite law school (particularly Harvard or Stanford)—seems to matter a great deal for women.

Using a set of conversations with senior lawyers, with whom we shared our basic findings and an initial draft to get feedback, we get some clues to why we see the numbers that we do. But we need to do a lot more qualitative work to understand what is really going on at these law firms. And that includes going beyond M&A to other areas of practice. For now, three things have come out from conversations with practitioners:

- First, our respondents thought it almost silly to think that someone who made it to equity partner would not be exerting maximum effort in the competition. However, they also did think that there was something to the ‘greedy work’ concept where men are perhaps slightly more able to do that kind of work at the margins (where everyone is working around the clock).

- Second, making ‘relationship partner’ really is about relationships; specifically, relationships with clients. And those usually happen either via the senior partners of the firm sharing their relationships more with some junior partners than others over long periods of time in lots of small bits and pieces (things like social events), eventually resulting in what almost seems like a natural transition. Maybe women do not do as well under this model, some of our respondents conjectured. A few respondents also pointed to the possibility that women who made it to deal leadership often had to get their own relationships through external networks that they built.

- Third, no one had good suggestions as to what was producing the Harvard/Stanford effect, or why Yale, the perennially top ranked law school, has relatively few graduates (both men and women) practicing in M&A.

Tracey E. George is the Charles B. Cox III & Lucy B. Cox Professor of Law at Vanderbilt University.

Albert Yoon is the Michael J. Trebilcock Professor of Law at the University of Toronto.

Mitu Gulati is Professor of Law at the University of Virginia.

Share: