Fair and Competitive E-marketplaces (F.A.C.E.) in India | The Business Users’ Narrative

Posted:

Time to read:

E-marketplaces are at the forefront of the digital revolution in India and are of undeniable importance to consumers and sellers/business users that operate upon it. Reinforced further by the COVID-19 pandemic, presence on large digital platforms has become unavoidable for business users to reach consumers, so much so that certain technology giants now act as ‘gatekeepers’ to various segments of the market.

The rise of E-marketplaces in India has however not been without problems. Numerous allegations of anti-competitive practices such as deep discounting, self-preferencing of private labels owned by platform operators, and opacity regarding search rankings, reviews and usage of data have been routinely levelled against platforms by their business users. Regulatory response to issues arising between platforms and their business users has thus far been amorphous and fragmented. Initially, E-marketplace regulation in India was subject to a light touch approach given its nascency. When regulatory focus finally shifted to E-marketplaces, consumer protection assumed priority.

However, as discussed in Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy’s latest Working Paper titled, Fair and Competitive E-marketplaces (F.A.C.E.) | The Business Users’ Narrative, pursuing a light touch approach in regulating platform—business user (‘P2B’) relationships may prove to be short-sighted even from a consumer welfare standard. Moreover, allowing privately owned digital platforms that lack democratic legitimacy to set the rules of Indian e-commerce without identifying and mitigating the long-term risks and the economic harm they can cause is highly undesirable.

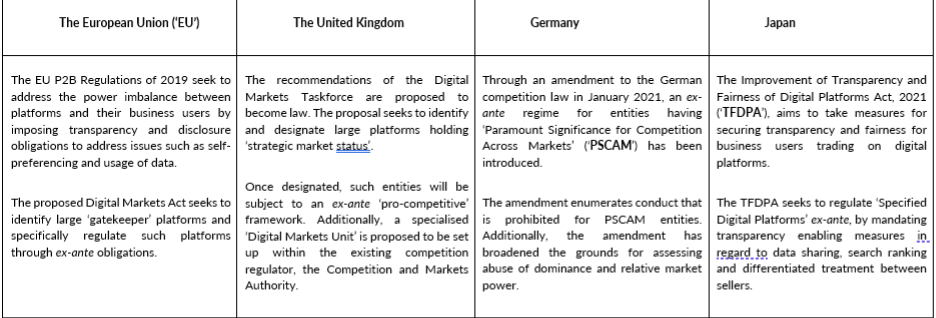

Regulatory efforts must therefore focus on developing an ecosystem that can nurture sustainable E-marketplaces. To contribute towards this goal, Vidhi’s Working Paper seeks to provide a detailed assessment of existing as well as proposed P2B competition regulation in seven international jurisdictions which lead the way in global regulatory response. Based on this, it seeks to explore avenues for carefully calibrated solutions in the Indian context that balance the need to keep markets fair and contestable, and to promote innovation.

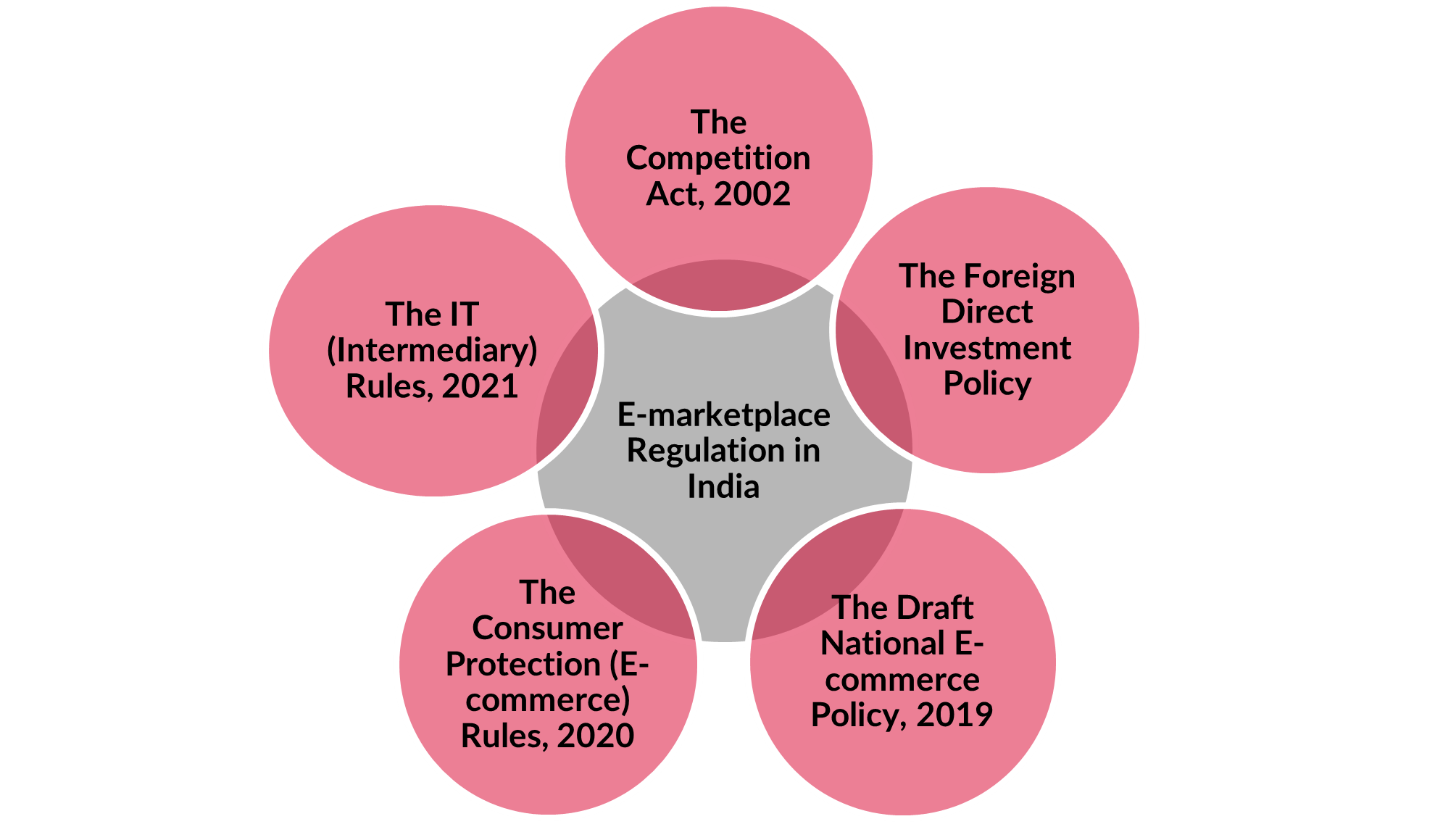

1. Extant Indian Regulatory Landscape governing E-marketplaces

Despite the existence of several statutory instruments (as illustrated), the scrutiny of P2B competition issues in E-marketplaces remains scant. For example, the Consumer Protection (E-commerce) Rules, 2020 and Draft National E-commerce Policy, 2019 are primarily consumer-welfare centric and therefore have very little bearing on P2B competition regulation whereas the Foreign Direct Investment Policy and the Information Technology (Intermediary Guidelines and Digital Media Ethics Code) Rules, 2021 are limited in their applicability as the former applies to only foreign-funded entities in India while the latter mandates obligations, particularly upon social media intermediaries, news publishers and news aggregators. The Competition Act, 2002 (‘the Competition Act’) does empower the Competition Commission of India to intervene ex-post once statutorily demonstrable anti-competitive conduct occurs. But the Competition Act may not suffice on its own given the statutory and enforcement limitations that arise in the context of digital markets and traditional anti-trust legislations.

As such, statutory instruments that comprehensively set the rules of the game ex-ante to maintain fairness and contestability in E-marketplaces in India are absent.

2. International Regulatory Response to P2B competition issues

3. Key Findings of the Working Paper

- Emerging international regulatory consensus to selectively designate and regulate large incumbent digital platforms that act as ‘gatekeepers’ to certain segments of the market.

- The preferred modus operandi of such selective regulation of gatekeepers is through complementary ex-ante competition tools that help prevent certain unfair conducts such as self-preferencing and anti-competitive leveraging, imposition of unfair contract terms such as most favoured nation clauses and exclusive selling, and to promote transparency in collection and usage of aggregated consumer data.

- Tighter scrutiny of mergers and acquisitions involving gatekeepers by introducing new thresholds as well as new substantive standards for such merger assessments.

- The establishment of specialised enforcement and monitoring units either within existing regulators or as a new authority to build expertise and aid enforcement in fast evolving digital markets.

Based on our findings in this Working Paper we believe that there is much to be gained from overhauling the existing regulatory approach to E-marketplaces. Increased contestability and fairer markets will not only promote innovation and encourage alternative platforms to come up but also allow small businesses and sellers to derive greater advantage from the growth potential of the platform economy. Ultimately, gains to consumers will ensue in the form of innovative and good quality products and services at cheaper prices.

This post originally appeared on www.vidhilegalpolicy.in.

Vedika Mittal is Senior Resident Fellow at Vidhi and leads Vidhi’s work in the field of Competition Law.

Manjushree RM is a Research Fellow working in the area of Competition Law at Vidhi.

Share: