In the United States, supervision is as old as banking, or nearly as old. State governments developed oversight regimes in the 1830s, and the federal government has played a permanent supervisory role since the 1860s. In this, the United States is unique. Most developed nations formalized bank supervision only after the 1930s banking crises, sometimes well after (Hotori and Wendschlag, 2019).

Now, of course, bank supervision—the tools government officials use to observe and shape bank behavior—is at the heart of global financial oversight. Yet scholars have at best a limited understanding of where supervision came from or why it has developed as it has.

In a recent essay, written for the Federal Reserve’s December 2020 conference, Bank Supervision: Past, Present, and Future, I urge financial and policy historians to take up the study of bank supervision. The essay maps a prospective history of bank supervision in the United States to show how supervisory histories will shine new light on the co-development of financial institutions and supervisory governance. Supervision, moreover, reaches into the lives of ordinary people, and the essay also highlights the ways supervisory history can enrich—and be enriched by—histories of science, gender, race, and sexuality.

In this post, I want to isolate the theory of bank supervision that motivates this turn to history (and which draws on ongoing work with Peter Conti-Brown). What, after all, is bank supervision? And what makes it distinct from other modes of governance? Our answer, detailed below, is rooted in the historical experience of the United States. It will nevertheless prove valuable for scholars working on other regions and to practitioners—such as those seeking to redesign post-Brexit financial governance in the UK—who continue to grapple with the place and purpose of supervision within the financial system.

Supervision, we argue, is best conceptualized as a two-part typology, consisting of actions—what we call external paradigms—and reasons for acting—what we call internal paradigms. These frames are united in the official discretion of the supervisor, discretion that enables government officers to mold behavior according to preferences and objectives that are, at times, distinct from any formal rules.

In terms of actions, supervision functions as a distinct mechanism of legal obedience—a means by which government or private actors seek to alter behavior. These mechanisms can be displayed on two axes, between public and private mechanisms, which require the exercise of coercive and non-coercive power. Supervision represents a choice for policymakers—in the United States, principally but not exclusively, Congress—distinct from other alternatives. It is a choice, as the graphic below indicates, which authorizes government officials to exercise substantial discretion about how to alter behavior. Defining supervision in 1954 (pp 166-7), the Federal Reserve identified numerous potential actions, including ‘the rendering of counsel and advice (private, non-coercive)’, ‘requiring of steps by bank management to correct unsatisfactory or unsound conditions found through such examination (private, coercive)’, or ‘the liquidation of banks (public, coercive)’.

Figure 1—Paradigms of Supervision: External

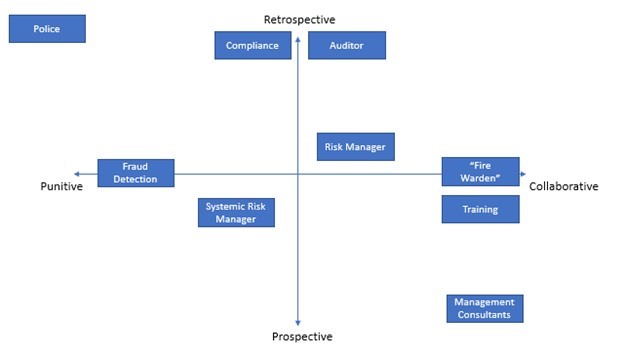

What supervision is, in turn, hinges on what supervisors think they are trying to accomplish, self-conceptions that divide not only according to an external logic of coercion vs non-coercion and public vs private, but also an internal one. Reasons for acting operate within a framework with axes spanning punitive to collaborative and from retrospective to prospective, as summarized in Figure 2. They also change over time. The alternatives presented here are evident in the Fed’s 1954 definition, and they become even more visible when comparing it with a more recent 2016 iteration (p 72). In 1954, the Fed emphasized ‘the rendering of counsel and advice on bank operating problems when requested, particularly in the case of smaller banks’, a statement that embraces the training and management consulting roles on the collaborative-prospective corner of the chart. Although the Fed may have been engaged in similar activities in 2016, it no longer held them as a defining feature of a now more compliance-focused supervision.

Figure 2—Paradigms of Supervision: Internal

This conception of supervision captures some of the descriptive and normative accounts offered recently by other scholars, without rooting that conception too much in a single point of time and imposing that moment—as defining the normative essence of supervision—on the rest of history (White, 2009; Calomiris & Carlson, 2018; Menand, 2019).

As a policy matter, the virtues (vices) of the Fed’s expansive view of supervision in 1954 and its more circumscribed view in 2016 are open to debate. And that debate must rest on a richer body of scholarly evidence than this brief definitional exercise can provide. The work of history is to understand the range of possible choices supervisors faced and why—given the inherent discretion—supervisors made the choices they did.

The paradigm we construct, again, is rooted in the historical experience of the United States. Other supervisory institutions, developed to oversee different financial systems and in different legal contexts, will look different. This is why historical analysis is so important. With luck, scholars will take up this call to make supervision more central to financial and policy history.

Sean Vanatta is a lecturer in US Economic and Social History at the University of Glasgow.

OBLB categories:

OBLB types:

Share: