Change in Parliamentary Regulations and Political Access of British Companies

Posted:

Time to read:

The recent publication of Peter Geoghegan's book on British politics highlights some of the severe malaise that afflicts the current British political set up. However, some of these problems, like the corporate-political nexus, are hardly recent. The interaction of the corporate sector and political representation is a highly controversial and important issue. At its core lies the concern that these interactions lead to the 'co-option' of politicians by large corporations, and that politicians will prioritise their own corporate interests over the interests of their electorate.

In our recent article, 'Bringing Connections Onboard: The Value of Political Influence', we examine the effects of corporate connections of British Members of Parliament (MPs). On 14th May 2002, a legislative amendment that came into place in the UK allowed British MPs with outside business interests to initiate parliamentary proceedings on issues that are related to their registered business interests (HC 841(2001-02)). At a time when half of the top 50 public companies in the UK had connections with a sitting MP, this amendment facilitated MPs with corporate connections to influence law making. We use this to provide a range of novel evidence. We demonstrate that higher equity returns for politically connected British companies are linked to increased political access, and not due to additional human capital introduced by the politician. We also show that politicians with corporate affiliation change their behaviour in parliamentary sub-committees. Although the benefits of political connection are more pronounced in countries with weak legal systems, we show that even in developed economies such as the UK political connections can have substantial effects.

To measure the effects of this amendment in parliamentary regulations we used data-mining techniques to study the financial performance, stock valuation, board composition and director backgrounds of FTSE 350 companies, as well as details about parliamentary committee attendance and activities of MPs. We cross-referenced this with the list of members of the House of Commons and House of Lords, their declared business interests, and the composition of key committees linked to government contracts and regulatory affairs, such as on defence, trade and economic affairs. Since the skills and expertise of MPs are unlikely to be influenced by the regulation, at least in the short run, this empirical strategy should solely capture the returns to the change in political access of companies.

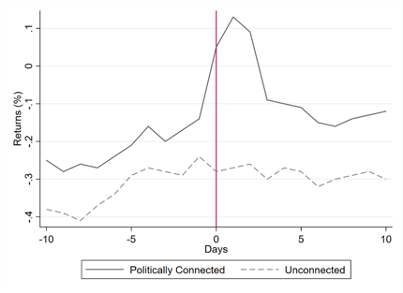

Companies with existing connections to the MPs experienced higher stock returns in the three-day window [-1,+1] surrounding 14th May 2002 when the parliament passed the amendment. Figure 1 illustrates the returns for companies connected to MPs compared to unconnected companies on that date.

Figure 1: Returns on the stocks of politically connected companies around the amendment of 14th May 2002 to MP's Outside Interests

In the longer term, we find that companies with MPs as directors or consultants experienced a substantial gain in value compared to unconnected companies, following the introduction of this legislation. These returns were more significant for companies where influence may be more important, for instance, those with concentrated (family) ownership, low attention to corporate and social responsibility, poorer environmental performance, and less transparent accounting practices. In contrast, companies with links to politicians not affected by this amendment (including Members of European Parliament, ex-MPs, etc.) did not gain in value after the amendment.

We identify channels of value creation that directly relate to the MPs' parliamentary activities. First, we analyse appointments to examine the effect of the change of regulation. The ability to initiate parliamentary proceedings and the memberships of parliamentary select and joint committees provide more considerable influence on lawmaking. Therefore, comparing the relative likelihood of members of the parliamentary committees, gaining a first-time corporate affiliation after the amendment of 2002 provides indirect evidence on the mechanisms through which MPs can affect corporate outcomes. Some anecdotal evidence finds that MPs with prior experience of being members of Parliamentary select committees were in high demand in the market for corporate directors after the amendment. For example, a member of the Treasury Committee from 1995-1998, was appointed by Lloyds Bank in 2004. MPs with corporate affiliations were also appointed to parliamentary select and joint committees: A prominent MP who held directorships in Alliance UniChem (now Alliance Healthcare) and British American Tobacco in May 2002 was appointed to the joint committee on Tax Law Rewrite in December 2002.

After the 2002 amendment, MPs with corporate affiliations are more likely to get appointed to parliamentary select and joint committees. Second, at the intensive margin, we hand-collect information on the attendance in parliamentary committee meetings from the public records of UK and examine the behaviour of MPs with corporate affiliations in such meetings. We employ data-mining algorithms to gather data on parliamentary committees. Relative to MPs with no corporate connections, connected MPs are more likely to sit on select and joint committees after the amendment, and attend more meetings.

Focusing on one observable substitute activity, registered political donations, we find that politically connected companies decrease political donations in the post-2002 period with respect to unconnected companies. Our results are not contaminated by a general downward trend in political donations—companies with other forms of political connections (access to Members of the European Parliaments and ex-MPs) do not reduce contributions to political parties post-2002.

Finally, we find that the higher returns generated by the 2002 amendment are concentrated among politically connected companies with family control, lower accounting transparency and lower social performance. These results are consistent with the view that the returns to higher access to political capital are more significant for companies characterised by lower transparency.

To what extent is the corporate clientism of elected politicians socially desirable? As we see from our results, the companies that benefit more from political connections are not the best corporate citizens (for example, those with poor environmental performance and opaque accounting standards). The role of large corporations in influencing democratic processes is increasingly coming under scrutiny. Our results have implications for the design of policy aimed at regulating and/or restricting these political and corporate interactions, particularly in light of the substitutive relationship between direct access to influential politicians and political donations. How corporations combine different channels of political influence is an essential question for regulators concerned with, for instance, revolving door arrangements.

Swarnodeep Homroy is an Assistant Professor of Finance at the University of Groningen.

Colin Green is a Professor of Economics at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology.

OBLB types:

Jurisdiction:

Share: