Margins: Estimating the Influence of the Big Three on Shareholder Proposals

Posted:

Time to read:

The Big Three index funds—Vanguard, BlackRock, and State Street—play an increasingly important role in proxy voting. Their influence derives from the fact that under US law, as well as that of many other jurisdictions, index funds have a legal right to vote their investors’ shares in corporate elections. Given index funds’ explosive growth in recent years, a key question emerges: what is the scale of index funds’ influence over corporate elections?

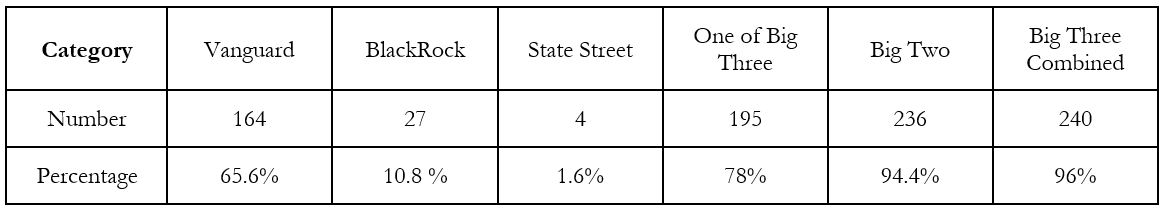

As I discuss in a forthcoming paper, ‘Margins: Estimating the Impact of the Big Three on Shareholder Proposals’, the Big Three are the largest shareholders at a staggering number of the 250 largest public companies as calculated by Fortune (the ‘Fortune 250’). The Big Three combined are the largest shareholder in 96% of Fortune 250 companies. Vanguard and BlackRock combined (the ‘Big Two’) are the largest shareholder in 94.4% of such companies, and Vanguard alone (the ‘Big One’) is the largest shareholder in 65.6% of such companies.

This Table reports the number and percentage of the 250 largest companies at which the Big Three serve as the single largest shareholder, taken either singly (first four columns) or in combination (final two columns).

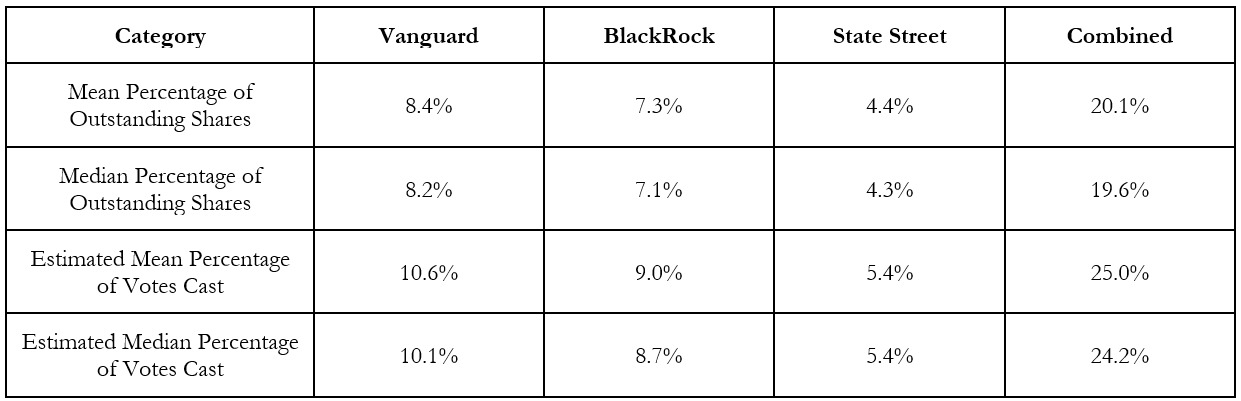

In addition, Vanguard, BlackRock, and State Street currently own an average of 8.4%, 7.3%, and 4.4% of outstanding shares, respectively, for a combined total of 20.1% of all shares. Because certain types of shareholders rarely vote, while the Big Three routinely vote their shares, the Big Three’s voting control generally exceeds the raw percentage of shares they own. Accordingly, this paper estimates that Vanguard, BlackRock, and State Street cast an average of 10.6%, 9.0%, and 5.4% of votes, respectively, for a total of 25.0% of votes cast [1].

This table reports the mean and median ownership rates for the Big Three individually and combined at the largest 250 publicly traded companies in the United States.

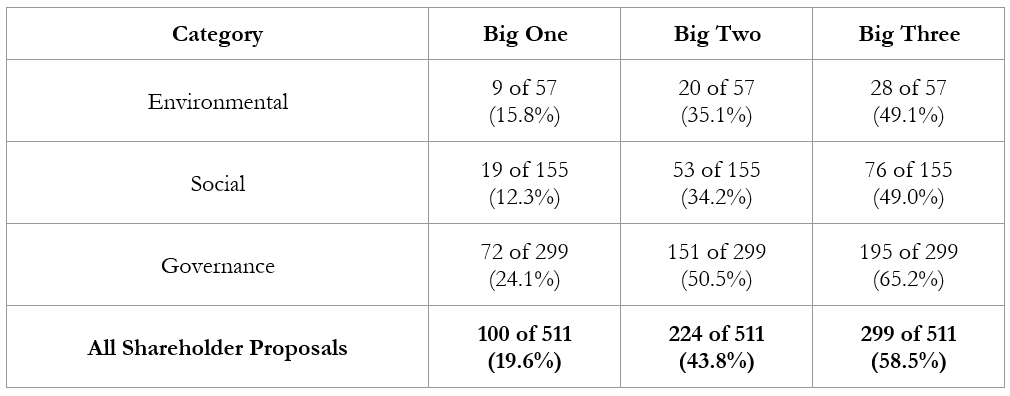

The trio’s control over voting outcomes is a function not only of voting power but also the margins for the ballot items under consideration. For uncontroversial votes (with greater than 25% margins), the Big Three will generally not be able to control the outcome, even acting in concert. When election margins are smaller than the voting control of the Big Three, Big Two or Big One, those agents will often have the power to determine the outcome. Applying this framework to shareholder proposals, roughly half of both environmental and social proposals were potentially under the control of the Big Three combined, while the same is true for approximately 65% of governance proposals. In total, nearly six-tenths of all shareholder proposals won or lost by margins of less than 25%, making them vulnerable to the Big Three combined, more than four-tenths won or lost by margins of less than 19.6%, making them vulnerable to the Big Two combined, and nearly one-fifth of shareholder proposals won or lost by margins of less than 10.6%, making them vulnerable to control by Vanguard alone.

This table provides data on the proportion of shareholder proposals that fell within margins of 10.6% (‘Big One’), 19.6% (‘Big Two’), and 25% (‘Big Three’) in calendar years 2018 and 2019.

Overall, these findings reveal that the Big Three may already be in a position to determine the outcome of the majority of shareholder proposals. These proposals often touch on quasi-political topics, such as climate change, gender pay disparities, board and employee diversity mandates, spending on political campaigns, and environmental initiatives. Given their controversial nature, it is likely that a substantial subset of the Big Three’s ultimate investors would disagree with the way that votes have been cast on their behalf, especially considering the frequently determinative impact of the Big Three’s votes.

The Big Three’s determinative impact on the fate of controversial shareholder proposals is even more concerning given the near-total discretion with which the Big Three cast their votes. Fiduciary duties obligate index funds to vote shares ‘in a manner consistent with the best interests’ of index fund investors. Problematically, the Big Three index funds make essentially no effort to discern the preferences of or solicit input from their investors about what those ‘best interests’ may entail. Instead, the Big Three rely upon small ‘stewardship teams’ who are vested with the power to unilaterally decide the ‘best interests’ of investors without any meaningful input from those investors. Given this untethered discretion and decisive power, stewardship teams may generate substantial agency costs by substituting their own preferences and values for those of their investors.

Ultimately, these results raise important questions for researchers and policymakers. Chief among them, what does ‘shareholder democracy’ look like in an era where three stewardship teams can decide the outcome of a majority of shareholder proposals with virtually no input from their investors?

Caleb N. Griffin is an assistant professor of law at the Belmont University College of Law.

---

[1] These findings are consistent with prior research in this area; see L Bebchuk and S Hirst, ‘The Specter of the Giant Three’ (2019) 99 BUL Rev 721, 736.

OBLB types:

Share: