Taxation of Income from Capital in India: Consistency Versus Priority

Posted:

Time to read:

Taxation of income from capital in India is widely debated among investors. Each year, prior to the annual budget, where the Finance Minister announces a slew of tax measures, there are appeals to do away with the complexities and to rationalise the tax treatment across incomes. This is a particularly vexed matter for financial markets in India where a variety of instruments are used to meet the financial needs of a company and its investors. Income from each of these instruments may be classified as dividends or interest on distributions and capital gains on transfer. Since these correspond, whether directly or indirectly, to the profits of the company, the decision to distribute profits may depend on the trade-off associated with the prevailing rates of tax. In principle, the tax system must be designed so as to make such a decision neutral. However, in India, deviations from neutrality have been deliberately introduced to meet overall macroeconomic objectives, be it the change in dividend taxation in 1997 to encourage companies to plough back profits or the exemption to long term capital gains in 2003 to provide a fillip to the equity market.

At the level of a corporation, profits may be distributed as dividends, issue of bonus shares, to finance a buy-back or ploughed back for future expansion. In India, until 2020, dividends were taxed in a unique manner. For ease of compliance, in 1997 a dividend distribution tax (DDT) of 10 per cent was levied by the company distributing such profits and they remained tax free in the hands of the individual. The rate of tax was subsequently raised to 15 per cent and grossing up of dividends was mandated in 2014. Further o make this tax progressive, in 2016, domestic investors receiving dividends in excess of INR 1 million ($13,064) were to pay an additional tax of 10 per cent. The DDT was criticised widely, particularly since no credit was available to foreign investors in their country of residence for such tax paid. Though this system was uniform in respect of the rate applicable to investor categories, it was not neutral. Finally, in 2020, heeding such requests, dividend is now taxable in the hands of investors. Reversion to the classical system can achieve progressivity and may perhaps also be useful from the point of view of investment vehicles such as debt-oriented funds, which were taxed at a higher rate. The rate of tax applicable on dividends paid by debt-oriented funds was 25 per cent as against 10 per cent charged from equity-oriented funds. Further, in 2014, to encourage investment in infrastructure, special treatment was extended to real estate investment trusts (REITs) and infrastructure investment trusts (InviTs) . Dividend distributed by special purpose vehicles (SPVs) to a business trust was exempt, provided that the trust owned a controlling interest in the SPV. Further, unit holders of these trusts were also exempt from dividend tax. Such exemption continues in the new system, although the dividend is taxable in the hands of the unit holders.

If the company retains its profits, it can issue bonus shares, undertake a buy-back or plough back profits into its business. In the first case, the cost of acquisition of the asset is nil for the investor and therefore all of the returns from new shareholding are profits. Further, in case of retention of profits or buyback, the share price may increase thus translating into capital gains on transfer. This is also true of units of funds, with underlying assets as shares or corporate debt. Capital gains in India are relatively more complex. Firstly, there is a distinction between short term and long term capital gains based on the period of holding the asset. The period specified varies between 12 months for listed equity shares, 24 months for unlisted equity and 36 months for debt and house property. To encourage equity investment, long term capital gains on sale of equity were exempt from tax between 2004 and 2018. In lieu of it, a securities transaction tax (STT), a turnover tax, was levied on transactions of listed securities. With the expansion in the equity market, it was estimated that capital gains of $483 billion were being exempt and, to expand the revenue base, the tax was reintroduced on equity at a lower rate of 10 per cent, on gains above INR 100,000. As of today, the rate of tax applicable on debt-oriented assets and unlisted assets, exempt from STT, is 20 per cent, although their cost of acquisition for computation of gain may be indexed. Whereas, short term gains are taxed at 15 per cent for equity and 30 per cent for debt. It is often pointed out that the difference in period of holding as well as rates, favourable to equity, must be rationalised.

Over the years, unlisted companies also began utilising profits to buy back shares in a bid to avoid taxes that would applicable in case of dividends and bonus. Therefore, in 2013, 20 per cent tax on buy back was introduced. This was later extended to listed companies in 2019. As a result, now all distribution of profits are taxable.

Subtle differences exist between tax treatment of instruments and incomes, which may have been introduced for a purpose. For example, to encourage liquidity in the equity market, income from equity has been taxed lightly. More recently, this is seen in the case of REITs and InviTs. However, the disparate treatment of capital begs the question if these have indeed worked and if these remain important.

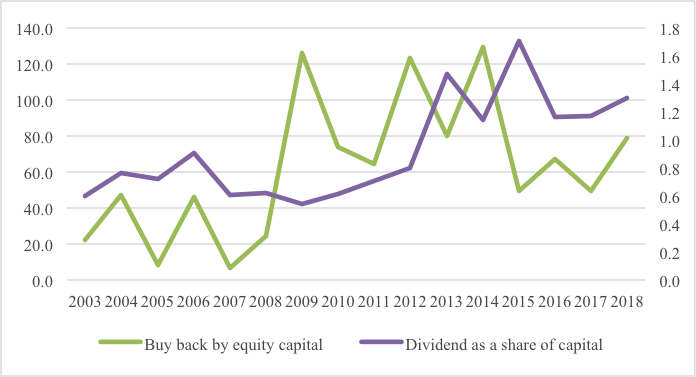

Figure 1 Value of buy back and Dividend as % of equity capital for top 500 listed companies

Source: CMIE

Differences in taxation of profits can present a trade-off, resulting in distribution that is tax efficient. This is observed for listed companies in 2013, when implementation of a buy back tax dampened value of buy back, and then again in 2016 on imposition of additional DDT that led to a decline in dividend pay-out.

On the other hand, the ability of tax to influence investment decisions is less clear when pattern of investment among mutual funds, REITs and InviTs are observed. Debt continues to be a large proportion (40 per cent) and in case of REITs and InvITs the amount received so far is fractional compared with the overall foreign investment. This perhaps compels a re-examination of the taxation of capital in India.

Therefore, while overall profits of companies may respond to changes in tax, the overall investment decisions in financial markets are driven by various other factors. If that is so, then the difference may be retained to encourage corporations to plough back profits or distribute. The present tax structure favours reinvestment through a higher rate of tax on buy back and dividends. This may prove vital for the revival of firms during the current crisis imposed by the pandemic, provided that individuals with peak incomes do not choose to incorporate merely to avoid taxes. This is particularly so since the Government imposed a surcharge on top incomes in 2019, thus making peak personal income tax rates substantially higher than existing corporate tax rate. On the other hand, tax may not be the tool to influence investment decisions in the financial markets. It is therefore rational to introduce a more uniform treatment across financial market instruments.

Suranjali Tandon is an Assistant Professor at the National Institute of Public Finance and Policy, India.

Share: