The default division of powers in Dutch company law allocates strong control rights to shareholders, including the power to appoint and dismiss board members and amend the articles of association. Dutch law allows the exercise of such control rights to be restricted significantly in the articles of association. Our empirical research shows that Dutch listed companies make extensive use of this possibility, with 76.1% of the companies limiting appointment rights, 71% limiting dismissal rights and 88.5% limiting the power to amend the articles of association. We believe this mechanism can provide inspiration on how to practically combine stakeholder governance with traditional control rights for shareholders.

We have conducted empirical research into the inclusion of so-called ‘oligarchic clauses’ in the articles of association of Dutch listed companies, both listed on a Dutch stock exchange (which we refer to as ‘domestic listed’) and (solely) on a foreign stock exchange (which we refer to as ‘foreign listed’). Oligarchic clauses are provisions in a company’s articles of association that limit the power of shareholders to freely exercise their control rights. Dutch company law allows for a broad range of these types of clauses. In our empirical research, we have distinguished three broader categories:

- clauses pursuant to which shareholders can only exercise their control rights following a proposal to that effect by another corporate body;

- clauses pursuant to which the implementation of a resolution by the general meeting is subject to (prior or subsequent) approval by another corporate body; and

- clauses that impose heightened majority and/or quorum requirements on the exercise of shareholder control rights.

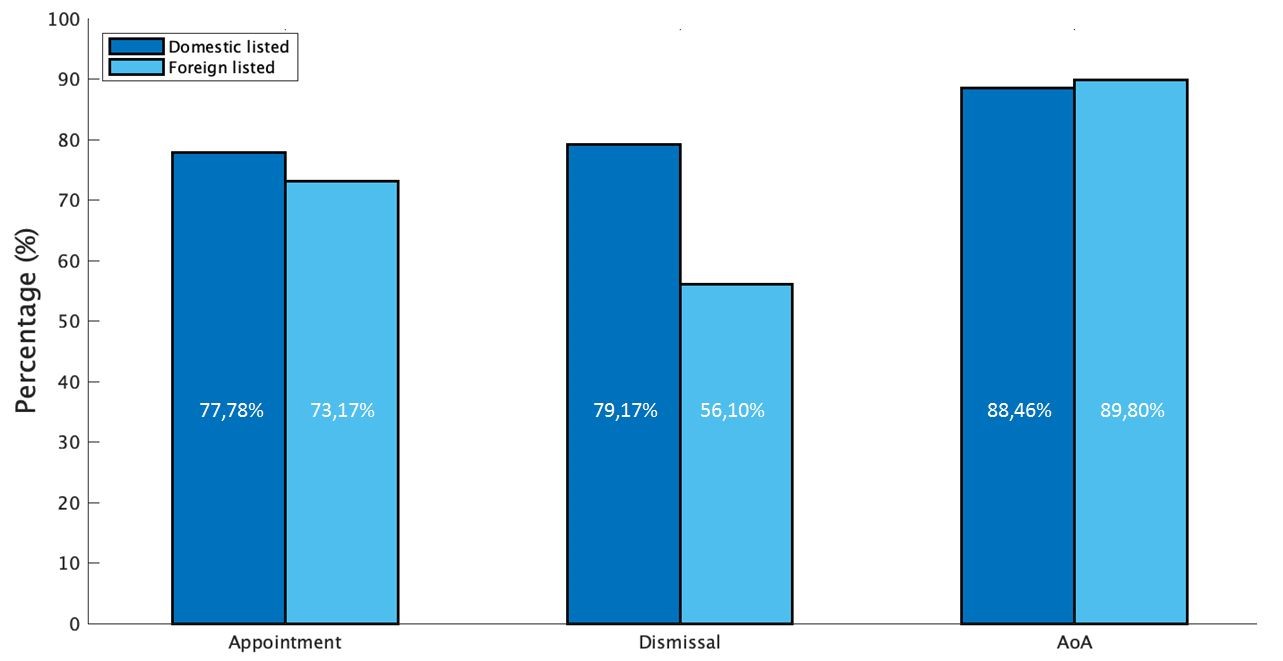

Our published research into limiting powers regarding (i) the power to amend the articles of association (part one and part two) and (ii) the power to appoint and dismiss management board members, shows that Dutch listed companies make extensive use of these type of clauses. Expressed in percentages, the following amount of domestic and foreign listed companies limit these shareholder powers:

As pointed out above, our data shows that on average a smaller percentage of foreign listed companies make use of these types of clauses. However, foreign listed companies that do use these clauses limit these shareholder powers more extensively (by using more binding nomination rights instead of non-binding nomination rights, higher majority and quorum requirements, etc). The lower percentage of foreign listed companies using these types of clauses is also explained by the fact that a larger number of foreign listed companies have one (or more) controlling shareholder(s), which limits the need and/or room to use these clauses. As a result, we cautiously conclude that it seems that foreign listed companies incorporate Dutch legal entities—at least in part—in order to make use of the protection provided by these types of clauses.

Oligarchic clauses address the mismatch between stakeholder-oriented governance and shareholder-oriented allocation of control rights

We come to the conclusion that the broad use of these types of clauses can be explained by a mismatch between the Dutch stakeholder-oriented governance model and the relatively shareholder-oriented allocation of control rights under default Dutch company law rules.

The current ‘shareholder-friendly’ allocation of powers provided for in Dutch company law is based on the principle that the residual power is vested with the shareholders. Similar to many other jurisdictions, these rights include, amongst others, the power to appoint and dismiss board members and amend the articles of association. This reflects the predominant view in 1929, when the current governance structure of Dutch companies was introduced. At that time, the company was primarily viewed as a contract between shareholders; a type of partnership intended to serve shareholder interests and employing a principal-agent inspired governance model. Prevailing doctrine in the Netherlands (still) provides that shareholders may primarily serve their own individual interests in exercising their rights (Dutch Supreme Court, 30 June 1944, Wennex, ECLI:NL:HR:1944:BG9449), subject to a general fiduciary duty to act reasonable and fair towards the company and other corporate stakeholders.

Gaining significant momentum in the 1960’s, there has been a shift in Dutch corporate law towards a stakeholder-oriented model. This stakeholder-oriented approach is reflected in board members duties. Board members are under an obligation to act in the best interest of the company, which is in principle determined by the continued success of the company-driven enterprise (Dutch Supreme Court, 4 April 2014, Cancun, ECLI:NL:HR:2014:797). It is generally accepted that, in fulfilling that duty, board members need to address the reasonable interests of the company’s stakeholders, including (but not limited to) its shareholders, employees and creditors. As a general principle, there is no one prevailing stakeholder interest that is placed above the interests of other stakeholders. The Dutch Corporate Governance Code 2016 further adds that the board should focus on 'long-term value creation' for the company and the company-driven enterprise.

As the company’s interests, as served by its board members, and its shareholders’ interests may not always be fully aligned, tensions can arise between shareholders and the management board. Meanwhile, shareholders are granted control rights that can—and they are in principle allowed to—be used to influence the management board’s composition and functioning. Oligarchic clauses allow a company to address this tension by (i) forcing cooperation between shareholders and directors in the exercise of control rights; and (ii) preventing vocal minorities from exercising disproportional control over the company. Our research shows that a large majority of Dutch listed companies make use of these types of clauses to address this tension and the protect the management board. Although these mechanisms could theoretically lead to a deadlock, in practice this is a (very) rare occurrence that can be remedied through court intervention.

Oligarchic clauses effectively force shareholders and the management board to cooperate when exercising shareholder control rights. Applicable board duties ensure that stakeholder interests are adequately addressed, while at the same time allow the company’s shareholders to exercise their control rights, albeit in a more limited way. We believe this Dutch system could provide inspiration for a practical mechanism to support the broader movement from shareholder value maximization to ‘stakeholder governance’, keeping in mind the traditional company law division of powers according to which shareholders have strong control rights.

Bastiaan Kemp is Professor of Corporate Governance and Corporate Regulation at the University of Maastricht, Vice-Academic Director at the Institute for Corporate Law, Governance and Innovation Policies and an attorney at Loyens & Loeff.

Philippe Hezer is a PhD Candidate at the Erasmus University Rotterdam and an attorney at Loyens & Loeff.

Sebastian Renshof is an attorney at Loyens & Loeff.

OBLB categories:

OBLB types:

Share: