Since the 2007–2009 financial crisis we observe more persistent deviations in the prices of closely related assets, so called ‘basis spreads’. This creates apparent profit opportunities and raises the question as to why they are not arbitraged away. In a recent Staff Report of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, we argue that post-crisis changes to regulation and market structure have increased the costs of participating in spread-narrowing trades for banks, creating limits to arbitrage. In addition, although one might expect hedge funds to act as arbitrageurs, we find evidence that post-crisis regulation not only affects the targeted banks but also spills over to less regulated firms that rely on bank intermediation for their arbitrage strategies.

Basis trades and their regulation

The law of one price – that a replicating portfolio producing the same payoff as an underlying asset be priced the same as the underlying asset – is one of the fundamental tenets of finance. Prolonged periods when the prices of related assets significantly deviate from each other therefore suggest ‘limits to arbitrage’: the inability of investors to eliminate mispricing through spread narrowing trades.

For example, in the chart below we compare spreads on credit default swaps (CDS) to spreads on the corresponding corporate bonds. The blue area in the chart shows the difference in the spreads, referred to as the ‘CDS-bond basis’. Exploiting this mispricing is a classic ‘arbitrage trade’ where an investor buys a corporate bond and simultaneously buys CDS protection on the bond when the basis is negative (the price of credit risk is cheaper in the bond market than in the CDS market), or sells the bond and sells the CDS when the basis is positive (see section 2.3 in our paper for details). Before the 2007–2009 financial crisis, the basis tended to be slightly positive, which was then attributed to the cost of shorting a bond; after the crisis, the basis has been persistently negative for the majority of CDS-bond pairs, which might be associated with the increased capital cost of holding bonds on banks’ balance sheets. Similar patterns hold for basis spreads in a number of other asset classes.

Might these deviations from parity persist because post-crisis regulations increased the cost of participating in spread-narrowing trades for banks? To answer this question, we need to consider the effects of post-crisis regulation on the different elements of a basis trade.

Consider again the CDS-bond basis trade and assume a bank wants to exploit a negative basis by buying a bond and buying a CDS. The long position in the corporate bond would be financed through a repurchase agreement (repo), with the bank borrowing cash and posting the corporate bond as collateral. The position in the single-name CDS requires funding only for the margin requirement on the contract and the fair value of the contract, both of which would usually be funded in the unsecured funding market. Thus, the overall profit of the CDS-bond basis trade depends on the CDS-bond basis net of the interest paid on the corporate bond repo, and the cost of financing repo haircuts (if any), CDS margin, and CDS fair value.

Under the pre-crisis regulatory regime, the repo position in the corporate bond affected the duration of the bank’s liabilities but did not impact Tier 1 capital requirements. Thus, the only impact of the trade on the Tier 1 capital requirements was through recognition of the potential future exposure of the CDS position.

In contrast, under the post-crisis regime, the supplementary leverage ratio (SLR) requires that banks recognize the full notional of the repo position. Thus, every dollar of trade exposure in the CDS-bond basis is reflected as more than one dollar of exposure on a regulated institution’s balance sheet, limiting its ability to participate in the trade.

Arbitrage activity and profitability for regulated institutions

In our paper, we document the components of typical basis trades across a number of markets – U.S. nominal term structure of interest rates, foreign exchange, and U.S. credit. Most of the trades that we describe have at least one component that is a cash product – funded through the repo market – and one component that is a derivative. Thus, changes in the regulatory environment that discourage banks from participating in either repo or derivative markets also discourage these banks from participating in spread-narrowing trades.

As an example, the chart below shows a measure of activity in derivatives markets, the gross notional outstanding in USD equivalent for interest rate, foreign exchange, credit, equity, and commodity over-the-counter derivatives. While the exponential pre-crisis growth in activity has slowed considerably post-crisis, we see a marked decline coinciding with the post-2014 period when many new regulations such as the SLR and liquidity coverage ratio were being implemented.

More specifically, we show in the paper that U.S. global systemically important banks (G-SIBs), subject to the strictest post-crisis regulations, have indeed adjusted their repo and derivative market activities since 2014. In particular, U.S. G-SIBs have significantly reduced their activity in repo markets relative to the pre-crisis period and to non-G-SIB banks. In derivative markets, we find that changes in the gross notional outstanding of non-centrally cleared OTC derivatives are positively correlated with the gross notional traded between dealers. Moreover, for interest rate and foreign exchange derivatives, some of the derivatives most affected by post-crisis regulations, the positive correlation has become stronger since the regulations came into effect around 2014.

In addition to these quantity measures, we also calculate the return on equity (ROE) that a bank can achieve on a basis trade, accounting for the regulatory treatment of all of the components of the trade under both the pre-crisis and the post-crisis regulatory environments.

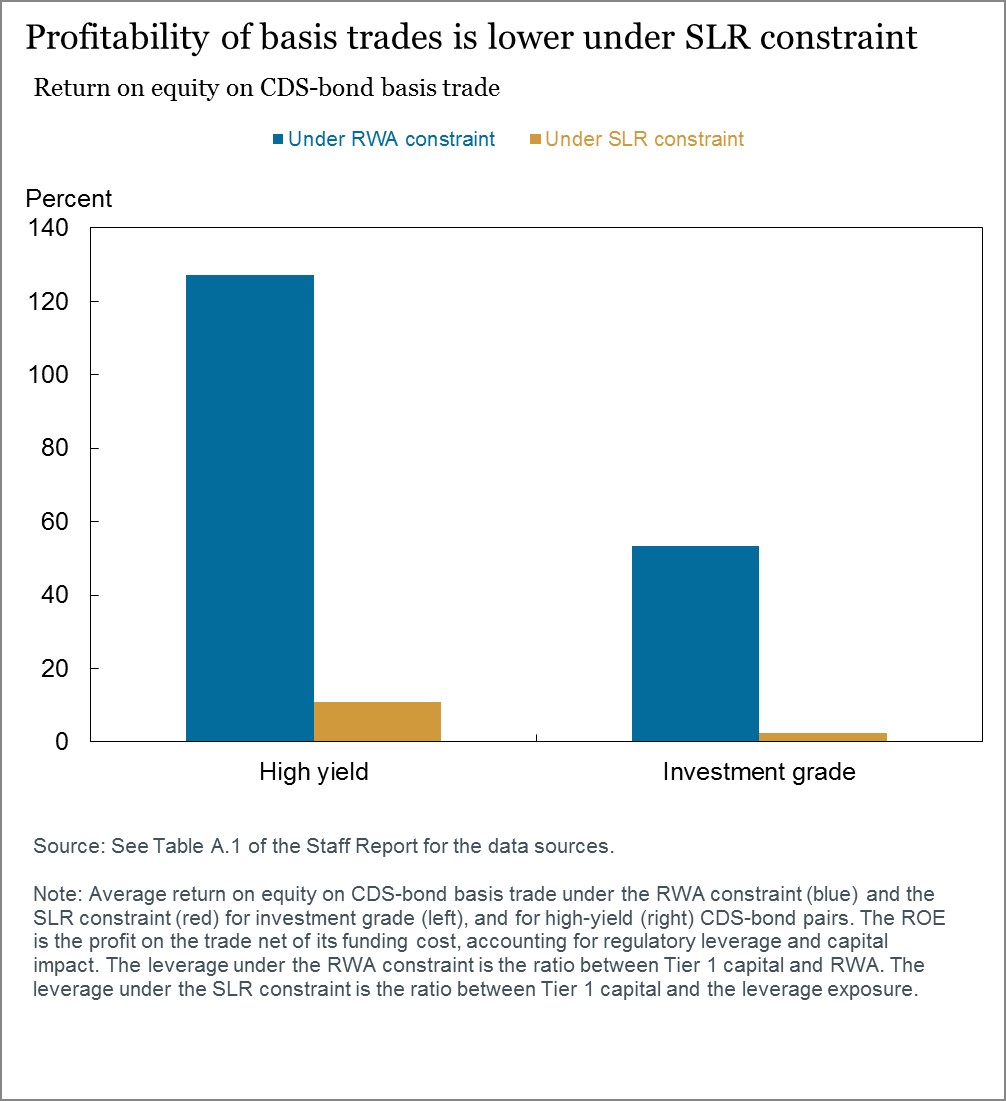

The next chart compares the average ROE for CDS-bond basis trades under risk-weighted assets (RWA) versus SLR constraints. For a detailed description of these measures as well as ROE measures for other basis trades, see our paper.

As the chart indicates, the ROE is significantly lower under the SLR constraint relative to both the RWA constraint and to the 10-15% ROE that most large banks target. Even though basis spreads have frequently been larger post-crisis than pre-crisis, regulatory changes imply that the basis trades are not sufficiently profitable from the perspective of regulated institutions, even at these elevated levels.

Why don’t non-bank arbitrageurs step in?

The question then is why less regulated arbitrageurs such as hedge funds don’t substitute for banks’ lower arbitrage activity. Our hypothesis is that, to the extent that arbitrageurs rely on regulated institutions for funding, clearing, and execution services, even non-regulated arbitrageurs may be impacted by post-crisis regulations.

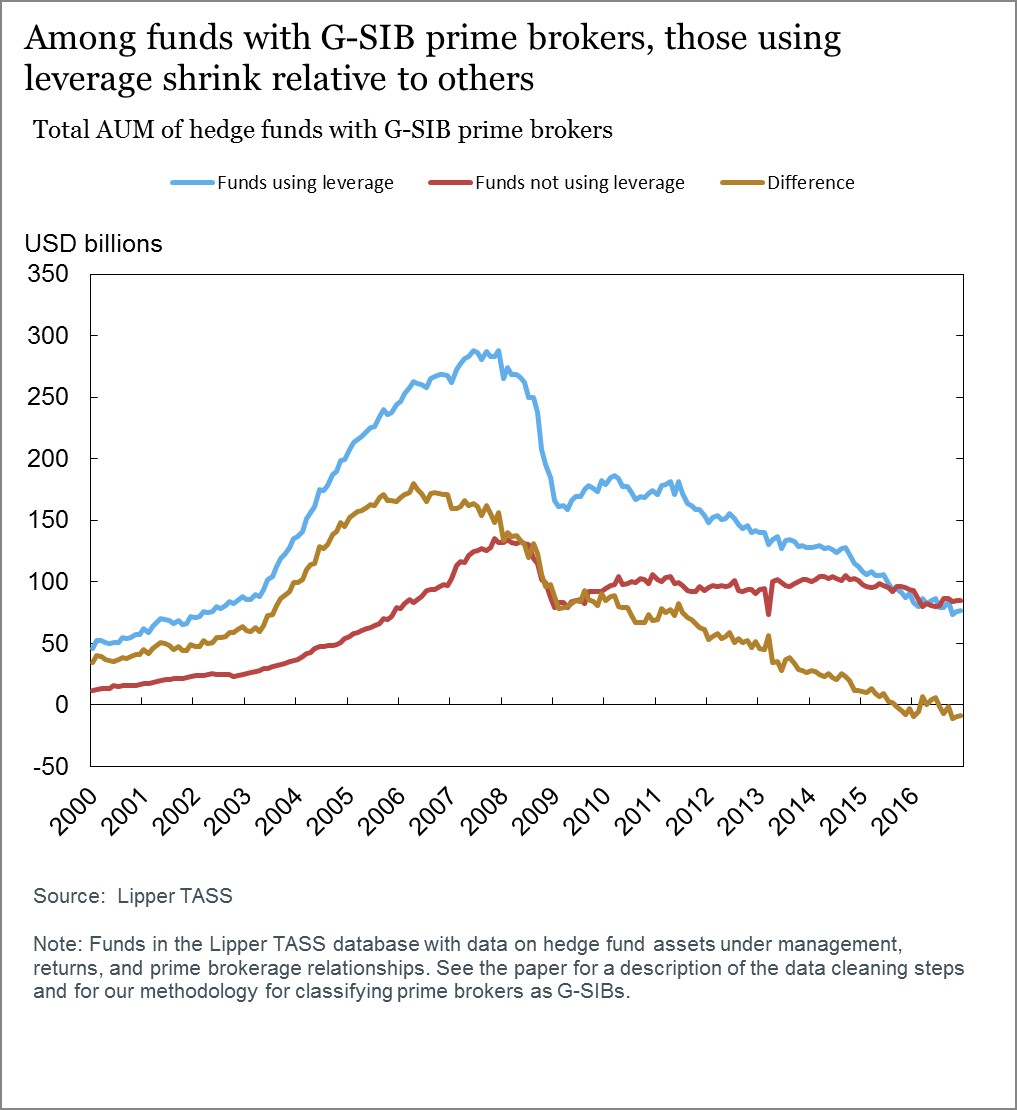

Consistent with this hypothesis, we find evidence that levered funds using G-SIB prime brokers have been differentially affected in recent years. The next chart shows that assets under management (AUM) have significantly declined in recent years for levered funds that use a G-SIB prime broker relative to unlevered funds that use a G-SIB prime broker.

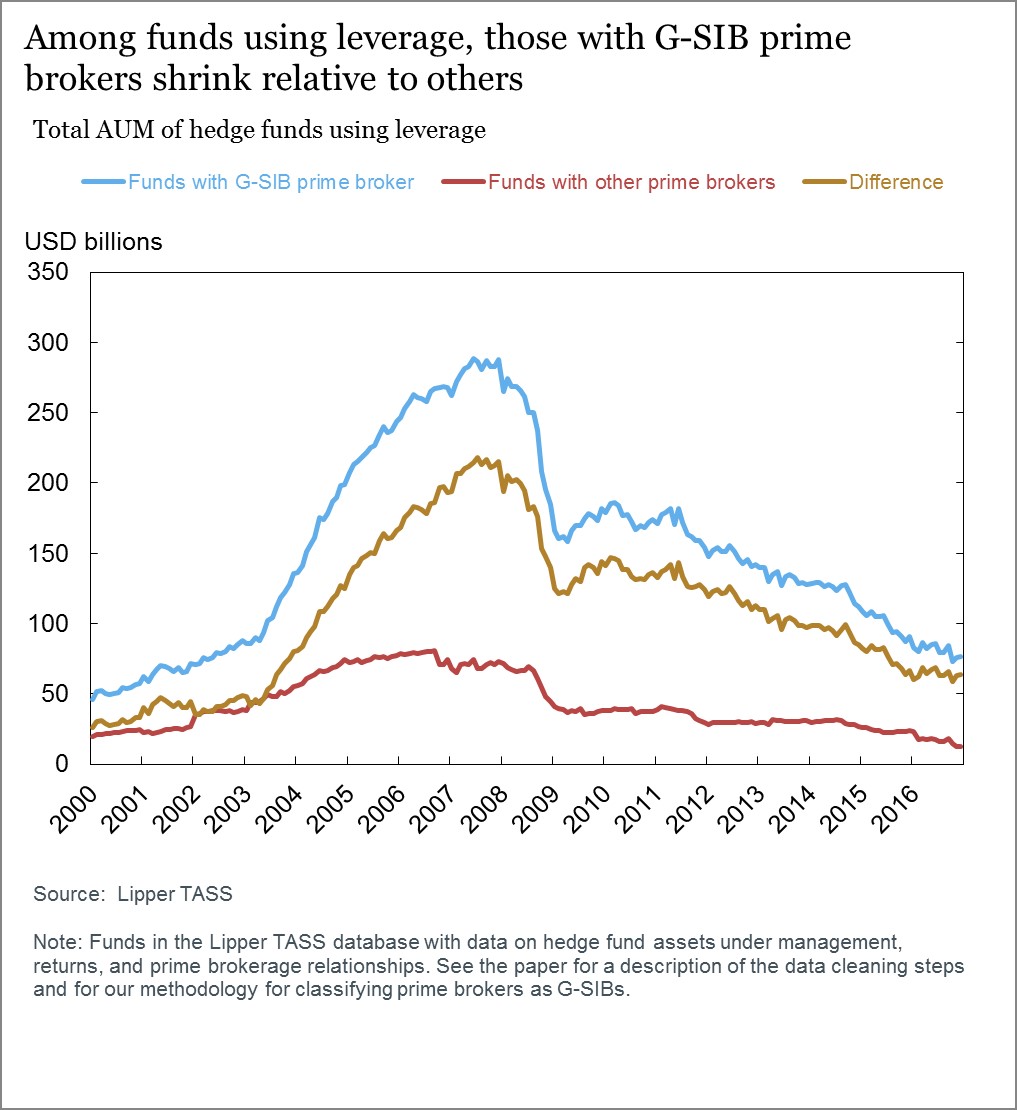

The next chart shows that, among levered funds, aggregate AUM has significantly declined for funds that use a G-SIB prime broker relative to funds that do not use a G-SIB prime broker, a result that reflects the declining number of levered funds using G-SIB prime brokers.

Finally, we show in the paper that performance has also been affected. Alongside the overall decline in hedge fund performance in recent years, levered funds using G-SIB prime brokers have underperformed relative to unlevered funds using G-SIB prime brokers on a value-weighted basis.

Summing Up

Taken together, our results suggest both a direct effect of regulation as well as a pass-through of regulation from the directly affected banks to other parts of the financial sector that rely on the regulated sector for intermediation. Of course, the costs of these limits to arbitrage must be weighed against the increased resiliency of both the regulated sector and the financial system as a whole, which are not quantified/addressed in our paper.

Nina Boyarchenko and Thomas Eisenbach are senior economists at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

Pooja Gupta is a senior associate for policy and markets analysis in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Markets Group.

Or Shachar and Peter Van Tassel are economists at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

OBLB categories:

OBLB types:

Share: