Securities Litigation Against Foreign Private Issuers in the United States

Posted:

Time to read:

Two of my recent articles examine securities class action litigation and SEC enforcement against foreign corporations seeking to tap American capital markets (see here and here). To evaluate public and private actions, the two sides of the same enforcement coin, the articles review doctrinal developments and ten years of class actions and enforcement actions filed between 2005 and 2015. This timeframe is centered on the crucial turnabout in the extraterritorial application of the federal securities law, the 2010 US Supreme Court decision Morrison v National Australia Bank (‘Morrison’). In Morrison, the late Justice Scalia mounted an attack on plaintiffs with tenuous connections to U.S. capital markets. The first article demonstrates that the risk of class action litigation has become more manageable from a foreign issuer’s perspective. The second piece suggests that the SEC has not responded to changes in private litigation and continues to prefer a low-key enforcement approach.

In this post, I would like to outline some findings of the first article. Cross-listing in a non-domestic securities market such as the U.S. generates tangible economic benefits for an issuer. Scholars mainly explain this by the high quality of U.S. law (i.e. legal bonding); bonding to the market’s institutional environment and reputational signaling; and an increased ability to raise capital and attract investor attention. Cross-listing in a jurisdiction such as the United States also carries considerable costs because of the extensive disclosure obligations imposed on reporting companies and a formidable litigation apparatus faced by cross-listed firms. When determining the expected value of a cross-listing program, a foreign executive must subtract those costs from the economic benefits of international securities trading.

Some costs are known and quantifiable before cross-listing. Others are ascertainable only upon occurrence of some future events. Morrison specifically concerns the second set of variables—the unknown costs of potential litigation. To examine the risk of litigation, the article reviews securities class actions five years before and five years after Morrison. It suggests that while the decision has not significantly altered the actual risk of litigation, it has provided certainty with respect to the ex-ante assessment of that risk.

The principal findings are as follows: first, as Morrison has affected the composition of the plaintiffs’ class, the mean and median settlement values have become much lower. Second, descriptive statistics do not indicate that Morrison has considerably altered the actual ratio of settlements to dismissals, decisions that mainly occur at early stages in litigation. With or without the new Morrison test, American courts dismissed about a half of the filed class action lawsuits. Yet, third, the data indicate that there has been a 10% reduction in successful dismissals. The fourth finding is an increase in smaller settlements, from $1,000,000 to $5,000,000. Fifth, more defendants chose to settle early in litigation and did not even file a motion to dismiss. One explanation may be that given the recent decrease in average settlements, risk-averse defendants may rationally prefer to settle. Another possible explanation, unfortunately, is an increase in the actual instances of fraud – a suggestion that calls for further research.

Sixth, the data indicate that most foreign defendants were listed on American exchanges, whereas firms trading their securities on the over-the-counter market were sued less than exchange-listed issuers. Therefore, hypothetically, when a foreign firm selects a specific cross-listing program, it incorporates in its decision not only the ex-ante known reporting costs associated with trading on U.S. exchanges but also the higher projected litigation costs.

To conclude, the principal findings are that litigation risk has become more measurable and lower. Morrison enables a firm to assuage irrational fears associated with the risk of litigation in the United States and to better determine the probability distribution of possible litigation outcomes. It may equip foreign issuers with the tools for a better appraisal of the expected value of a cross-listing program by assessing their level of exposure vis-à-vis possible bonding and exchange-trading benefits.

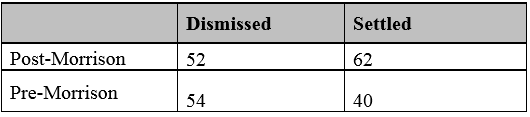

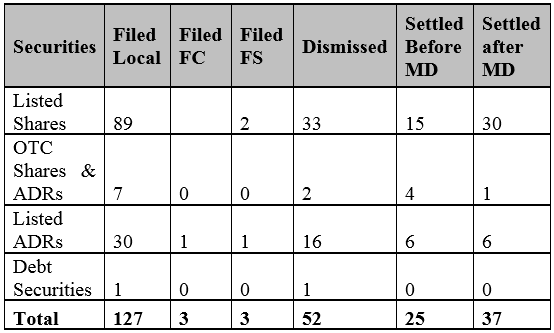

The tables and charts below present some of the findings. Table 2 shows dismissed and settled cases.

TABLE 2: DISMISSED AND SETTLED CASES

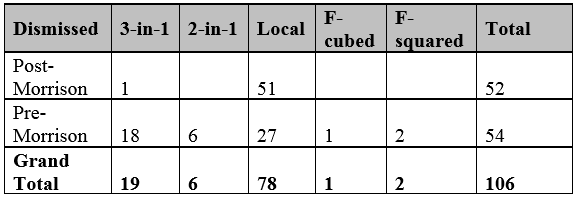

Table 3 summarizes the dismissal of cases brought by various subclasses of plaintiffs, including local Morrison plaintiffs (i.e. principally those who purchased the securities at issue in domestic transactions or on U.S. exchanges), f-cubed (foreign plaintiffs who purchased their securities on foreign exchanges), f-squared plaintiffs (U.S. plaintiffs who purchased the securities on foreign exchanges), and the combined cases involving two or three of the aforesaid plaintiff classes.

TABLE 3: DISMISSED

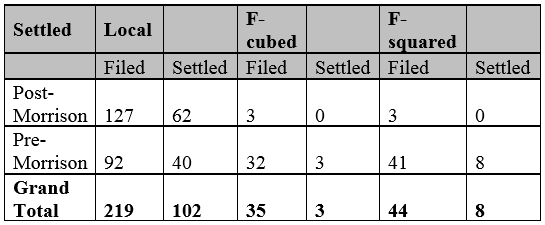

Claims brought by U.S. residents who purchased securities in the U.S. settled more often than claims of ‘global’ investors. Before Morrison, ‘f-squared’ American plaintiffs participated in more settlements than foreigners, i.e. ‘f-cubed’ plaintiffs.

TABLE 4: SETTLEMENTS AND PLAINTIFF CLASS

Table 5 shows that the average and median settlements have decreased after Morrison.

TABLE 5: AVERAGE SETTLEMENT VALUES

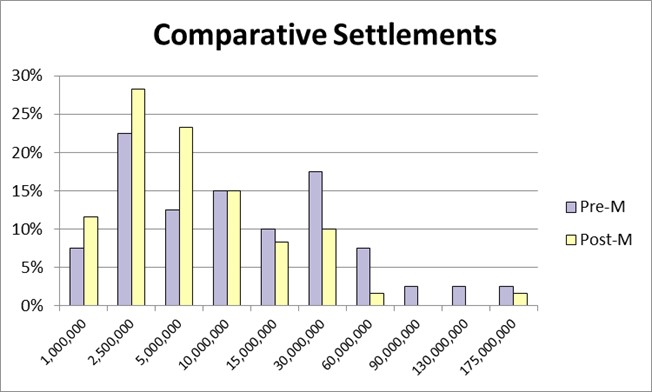

Figure 1 shows that post-Morrison, there was an increase in the number of smaller settlements ranging from under $1 million to $5 million.

Tables 6 and 7 demonstrate that more actions filed after Morrison settled —the pre-Morrison cases were dismissed in 56% of the sample cases, whereas after Morrison only 45% were dismissed. In as many as 20% of the post-Morrison filings, defendants preferred to settle fast. They did not wait for the outcome of their motions to dismiss and in several cases did not even move to dismiss. The Tables also illustrate that most cases were brought against defendants with securities trading on U.S. exchanges.

TABLE 6: PRE-MORRISON RESULTS

TABLE 7: POST-MORRISON RESULTS

To summarize, the main conclusion of this paper is that Morrison may have value to international companies in at least one area—the projected costs of litigation associated with cross-listing in the United States have become more ascertainable and possibly slightly lower than before Morrison. The second paper in this series examines if the SEC has responded to these developments and finds no determinable changes in enforcement against foreign issuers.

Yuliya Guseva is an Associate Professor of Law at Rutgers Law School.

This post is based on two papers: Extraterritoriality of Securities Law Redux: Private Litigation Five Years After Morrison v. National Australia Bank, Colum. Bus. L. Rev. 199 (2017); and The SEC and Foreign Corporations: A Path to Optimal Public Enforcement, 59 B.C. Law Rev. 2055 (2018).

OBLB types:

Share: