Financial Knowledge, Attitudes and Investment Choices of Italian Households. Evidence from the 2017 CONSOB Report

Posted:

Time to read:

- Introduction

The Italian Commissione Nazionale per le Società e la Borsa (CONSOB)’s Reports on Investment Choices of Italian Households gather evidence on the multifaceted drivers of financial decision-making – such as education, experience, behavioural biases, socio-demographic characteristics – and investment behaviours, such as portfolio choices and advice seeking.

The 2017 Report has widened the analysis to the building blocks of the so-called financial control (ie, planning, budgeting, and monitoring) underpinning savings and investment decisions, and to factors that may affect individual engagement in financial matters, such as financial anxiety and interest. Finally, special attention has also been devoted to the attitudes towards information on the risk-return characteristics of financial products.

- Actual and perceived financial knowledge

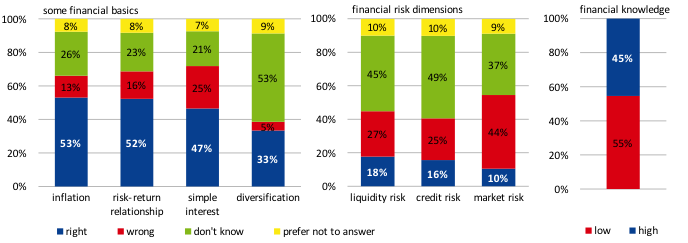

The 2017 Report confirms that the level of financial knowledge of Italian households remains largely inadequate. The proportion of respondents failing to answer basic questions (regarding, for example, inflation, risk-return trade-off, simple interest and diversification) ranges between 47% and 67% and rises further when understanding of financial risk dimensions (ie, market, credit and liquidity risks) is tested.

Fig 1 - Actual financial knowledge

The figures on the left hand side and in the centre report percentages of ‘heard and understood’, ‘heard but not understood’ and ‘never heard’ answers related to the perceived financial knowledge of: inflation (Q1); risk/return relationship (Q2); simple interest (Q3); diversification (Q4); liquidity risk (Q5); credit risk (Q6); market risk (Q7). The figure on the right hand side refers to the perceived financial knowledge factor indicator (see the 2017 Report Methodological notes). Source: 2017 Report on investment choices of Italian households.

A proportion of respondents (ranging from 32% to 41%) show inconsistencies between self-assessed and actual knowledge, generally accounting for an ‘upward mismatch’ as individuals report to have understood while being unable to define correctly the selected notion. Propensity towards upward mismatch is more likely among men, middle-aged groups and financially knowledgeable individuals.

Fig 2 – Perceived financial knowledge

The figures on the left hand side and in the centre report percentages of ‘heard and understood’, ‘heard but not understood’ and ‘never heard’ answers related to the perceived financial knowledge of: inflation (Q1); risk/return relationship (Q2); simple interest (Q3); diversification (Q4); liquidity risk (Q5); credit risk (Q6); market risk (Q7). The figure on the right hand side refers to the perceived financial knowledge factor indicator (see the 2017 Report Methodological notes). Source: 2017 Report on investment choices of Italian households.

Personal traits and inclination towards behavioural biases

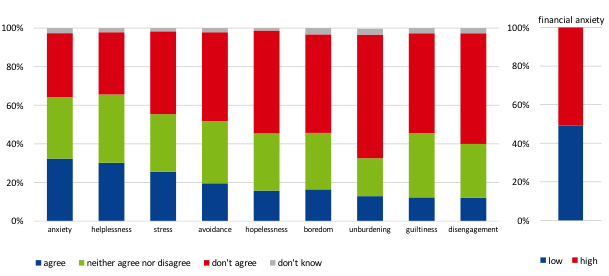

The CONSOB 2017 Report also focuses on those emotional states that may shape the individuals’ decision-making process, such as financial anxiety and interest in financial matters. Engagement with one’s personal finances triggers feelings of anxiousness in about 50% of cases, as measured by the overall individuals’ attitude towards selected financial tasks (eg, tracking one’s bank account) and financial problem solving (eg, bailing oneself out of distress). This emotional status is associated with poorer financial behaviour, in terms of financial planning, budgeting, and financial market participation. Financial apprehension becomes less frequent as financial knowledge rises, thus suggesting that education might successfully mitigate it.

Fig 3 - Financial anxiety

The figure on the left hand side refers to respondents’ opinion on the following nine statements: ‘Thinking about my personal finances can make me feel anxious’ (anxiety); ‘There’s little point in saving money, because you could lose it all through no fault on your own’ (helplessness); ‘Discussing my finances can make my heart race or make me feel stressed’ (stress); ‘I prefer not to think about the state of my personal finances’ (avoidance); ‘I get myself into situations where I do not know where I’m going to get the money to ‘bail’ myself out’ (hopelessness); ‘I find monitoring my bank or credit card accounts very boring’ (boredom); ‘I would rather someone else who I trusted kept my finance organized’ (unburdening); ‘Thinking about my personal finances can make me feel guilty’ (guiltiness); ‘I don’t make a big effort to understand my finances’ (disengagement); (single answer; scale type: 5-point Likert, from 1 – ‘strongly agree’ to 5 – ‘strongly disagree’). ‘Agree’ includes ‘agree’ and ‘strongly agree’, while ‘don’t agree’ includes ‘disagree’ and ‘strongly disagree’. The figure on the right hand side refers to the ‘PCA’ financial anxiety indicator (see the 2017 Report Methodological notes). Source: 2017 Report on investment choices of Italian households.

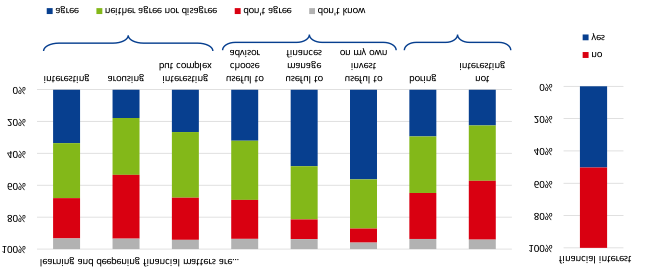

The 2017 Report also gauges interest in financial matters in terms of individuals’ disposition towards different levels of cognitive and emotional involvement (ie, whether financial learning is perceived as stimulating, interesting, useful or boring). Interest is expressed by half of the interviewees and rises with financial knowledge (see Fig 4). It is also the main driver underpinning individual background in financial matters, followed by experience in household budgeting, which is more frequent among women. Not surprisingly, financial background benefits from a wider set of inputs when financial knowledge (both actual and perceived) and interest in financial matters are high, while anxiety seems to work the other way around.

Fig 4- Interest in financial matters

The figure on the left hand side refers to respondents’ opinion on ‘learning and deepening financial matters’, the statements to be evaluated being: ‘interesting’; ‘arousing’; ‘interesting but hard to understand’; ‘useful to choose the financial expert suitable for me’; ‘useful to manage my personal finances’; ‘useful to make investment decisions on my own’; ‘boring’; ‘not interesting at all’ (single answer; scale type: 5-point Likert, from 1 – ‘strongly agree’ to 5 – ‘strongly disagree’). ‘Agree’ includes ‘agree’ and ‘strongly agree’, while ‘don’t agree’ includes ‘disagree’ and ‘strongly disagree’. The figure on the right hand side refers to the ‘PCA’ financial interest indicator (see the 2017 Report Methodological notes). Source: 2017 Report on investment choices of Italian households.

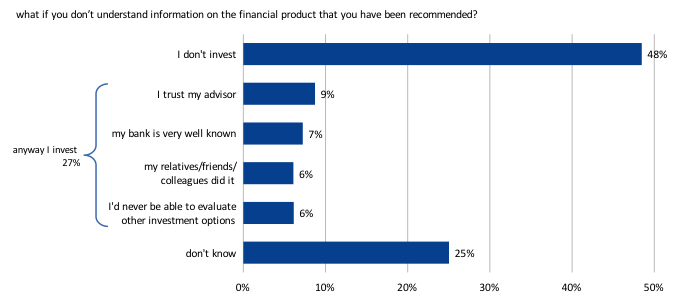

As for attitude towards risk, the vast majority of respondents are loss averse (consistent with their strong preference for risk free/capital guaranteed investment options). Moreover, about one-third of the sample shows inclination towards the so-called framing effect, as they prefer certainty when the choice set is positively framed and uncertainty when the choice set is negatively framed (or vice versa). Framing effects raise concerns for investor protection, given that financial information is among the main tools meant to empower individuals, reduce informational asymmetries and mitigate mis-selling risks. Even more alarming is a willingness to invest even when financial information was not understood, as reported by 27% of the 2017 sample (Fig 5). This inclination is more frequent among women, financially anxious and less literate respondents.

Fig 5 – Understanding of financial information and willingness to invest

The figure refers to the subsample of investors. Source: 2017 Report on investment choices of Italian households.

Financial control

Financial control can be defined as the individual’s capability to work out her own financial plan and to keep track of her own finances. Financial planning is not widespread, as it is reported by less than one-quarter of the sample. Almost all the interviewees having a plan review its progress, mainly on a biannual or a yearly basis. Having a financial plan is positively associated with income and wealth, as well as financial knowledge (both actual and perceived) and interest in financial matters.

More than half of respondents have a budget, although only 15% always stuck to it. More than 60% of the sample tracks spending, but only one-fifth of interviewees relies on written records. Budgeting and monitoring are positively correlated with financial knowledge (both actual and perceived) and interest in financial matters, whereas the opposite holds with respect to financial anxiety.

Financial control is key to saving. Among respondents reporting to save (61%), almost two-thirds do it on a regular basis and mainly on their own. Not surprisingly, the proportion of savers rises with the degree of financial control as well as with education, income, wealth and financial education. Major deterrents to saving are a tight budget and debt service, whereas, among personal traits, financial anxiety and lack of interest in financial matters show a significant negative correlation. Precautionary motives are the main reason for saving, particularly among the less educated, less literate and less wealthy individuals, while specific goals are reported to trigger saving only by 32% of respondents.

- Investment decision process

The quality of investment choices rests not only on knowledge but also on the understanding and the implementation of a correct decision process, both in its ex ante and ex post dimensions.

Italian investors (accounting for 45% of the sample at the end of 2016) keep being unaware of the building blocks that must be reviewed before investing: objective, holding period, risk tolerance, risk capacity, etc. Indeed, about 40% of the interviewees do not consider any of those, while three-quarters of the remaining respondents refer only to one item (mainly the holding period).

Moreover, only one-fourth of the interviewees ask for professional help (either financial advice or portfolio management), while more than half make investment decisions with the support of family, friends and colleagues (informal advice).

Investors relying on a financial intermediary are not totally aware of the extent to which the quality of the recommendations they receive depends also on the quality of the information they provide. Indeed, the percentage of respondents inclined to give complete and true information to the advisor or the portfolio manager is never higher than 36%, whereas 14% state that no details need to be disclosed.

Nadia Linciano is Head of the Economic Studies, Research Department of CONSOB and Paola Soccorso is senior economist at the Economic Studies, Research Department of CONSOB.

OBLB categories:

OBLB types:

Share: