Brexit Negotiations Series: 'Leaving the EU: impact on bank customers'

Posted:

Time to read:

While trading internationally used to be the reserve of large multinational corporations, the digital revolution has meant that SMEs are now born operating across borders and expect to be able to access international markets both for their inputs and to sell their products and services.

With the majority of firms’ international payments going through a bank, banks have become critical pieces of infrastructure that allow firms to grow through the benefits of international trade.

Given this vital role for banks in international trade, it is important to understand what leaving the EU by the UK means for the commercial banking sector. This blog examines what is at stake for banks, and the effect on their employees, investors and, crucially, their customers. It is this last mechanism—the effect on customers—which can mean that small changes in banking can have wider impacts on the rest of the economy.

UK banks have a lot at stake

In 2016 UK banks generated around 25% (£25bn) of their total revenues from clients and products linked to the EU.

Source: Oliver Wyman (2016), ‘The impact of the UK’s exit from the EU on the UK-based financial services sector’, report produced for TheCityUK.

Does it matter for staff and investors if banks relocate?

Current employees may find their UK-based role becomes redundant and they have to seek alternative employment within the UK or apply for new roles created in places such as Frankfurt, Paris or Dublin. Prospective employees may find that the scope for pursuing a banking career in the UK is curtailed. Overall, levels of employment in the UK banking sector are likely to be lower than would otherwise be the case. This effect will also ripple out beyond the banking sector to a range of closely related legal and professional services sectors that supply the banking sector.

Over the long term, some of the lower employment in banking would be expected to be offset by higher employment elsewhere in the economy as workers transition to other sectors, albeit at slightly lower wages. However, the adjustment could take several years and lead to a loss of productivity. Employment in banking is also likely to settle at a permanently lower level due to lower net immigration of financial services workers. This would have an impact on government revenues from sources such as income tax, national insurance, VAT and stamp duty as less high skilled international workers are attracted to work in the UK banking sector.

The impact on bank investors will vary according to the type of activity the bank undertakes. Banks that serve clients in multiple EU countries from a UK base could be expected to adjust their organisational structures so that their access to markets is maintained. Some banks will be better positioned to make these adjustments (e.g. where they already have a subsidiary in Europe); others will be at a relative disadvantage and face losing market share. This adjustment process will be risky for banks, requiring skilled management to navigate the transition successfully.

There will be costs associated with this transition to new structures, and probably higher costs in the new ‘steady state’ as a result of a less efficient model for delivering banking services than is currently the case. However, as most banks will be facing similar cost shocks, a large proportion of the additional costs are likely to be passed on to customers, rather than having a long-term impact on profitability. The impact on customers has received relatively little attention to date.

What about the users of banking services?

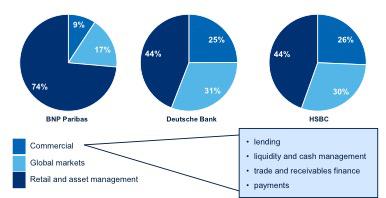

So who are the users of banking services? One way to think about this is to look at where banks receive their revenues. Figure 2 shows the split between commercial, wholesale and retail users, for three large banks. All of these users could be affected by Brexit in different ways. Perhaps an area that has received the least attention are the commercial customers, the corporates using banks for lending, cash management, payments and, importantly, cross-border transactions.

Figure 2 - Global revenues by business segment, latest available data

Source: Company accounts.

Massive cross-border transactions between UK and EU businesses

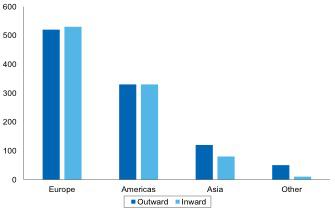

When the impact of Brexit on commercial cross-border transactions is considered, the focus is usually on trade. The total amount of trade between the UK and other EU member states is certainly large, at around £520 billion in 2015, but this is not the full picture. The links between the UK and other EU Member States run deeper than this, with cross-ownership of companies totalling some £1 trillion in 2015 (see Figure 3), and a broadly balanced split of ownership between the UK and other European countries/other EU Member States.

Figure 3 - The value of subsidiaries and branches in EU/UK owned by UK/EU companies

Source: ONS (2015), ‘Foreign direct investment involving companies’.

Based on the official statistics of revenues and net corporate worth in the UK National Accounts,[2] the subsidiaries represented in Figure 3 are likely to have revenues totalling around £250 billion per annum, which provides an indication of the amount of intra-company cross-border transactions taking place. This would come on top of the transactions required for the £520 billion of trade each year.

The scale of the cross-border transactions being conducted suggests that even a small increase in transaction costs could produce a significant cost for the users of banking services, just as a small financial transaction tax can create significant costs in the financial system.[3]The exit of the UK from the EU could affect the cost of these cross-border transactions for a number of reasons. In the first few years, while the overall regulatory regime is likely to be similar, there could be increased costs due to the loss of EU ‘passporting rights’ for banks. These rights allow banks to provide a wide range of banking services for their clients operating between the UK and the rest of Europe. This means that companies can conduct intra-EU transactions through a single bank, giving customers access to economies of scale and scope. These passporting rights are likely to be lost, and for many users of banking services (especially in the UK), this is likely to result in the duplication of transaction costs.

In the longer term, financial regulation may begin to diverge more fundamentally, potentially affecting transaction costs. The UK has tended to lead financial regulation in many areas in Europe, but this leadership role is likely to change once outside of the EU, and significant differences in approach could arise. Needing to comply with different regulatory regimes creates additional costs for banks, which are likely to be passed on to end-users. On the other hand, the new regulatory regime could reduce transaction costs if it were more efficient, but achieving such an improvement is quite uncertain.

In the long run, more fundamental shifts in the location of banks would have implications for end-users. If the UK’s departure from the EU results in some non-UK wholesale banks leaving London, their commercial arms are also likely to exit, lessening choice and competition in the UK. New commercial banking institutions would also be less likely to enter the UK if the transaction costs rose and UK-based banks no longer had passporting rights. These effects could weaken competition, and reduce innovation in banking services.

Will the UK leaving the EU affect end-users?

It is difficult at this stage to predict what could be the impact of leaving the EU on transaction costs, and hence the end-users of banking services. The impact depends on the outcome of the negotiations, and on how the banking sector itself responds to the changes. What is clear, however, is that the potential impact is significant simply because of the sheer numbers of transactions being conducted across borders, relying on the efficiency of the banking system. People and companies using banking services should not be forgotten in the forthcoming negotiations.

Luis Correia da Silva is Partner at Oxera.

[1] Office for National Statistics (2016), ‘UK National Accounts, The Blue Book: 2016’, July. See, also, the related Office for National Statistics (2016), ‘UK input-output analytical tables’

[2] Oxera explored the implications of a proposed EU financial transactions tax in Oxera (2014), ‘What could be the economic impact of the proposed financial transaction tax?’

[3] Oliver Wyman (2016), ‘The impact of the UK’s exit from the EU on the UK-based financial services sector’, report produced for TheCityUK. This includes UK subsidiaries of international banking groups.

OBLB categories:

OBLB types:

OBLB keywords:

Share: