If Brexit fails, it will do so because withdrawal happens suddenly and with no indication about the future arrangements that will replace membership in the EU. In this short note, I explain how this process is likely to unfold. It may still succeed. It may be that, as the current United Kingdom government hopes, Britain will become a leading trading nation outside the European Union, without political and social friction and without going through a painful economic downturn.

For Brexit to succeed, we need a period of transition to the new trade environment. A smooth withdrawal from the EU should allow time for the UK to negotiate protection for London and for financial and related services (which may in the end prove unachievable), to secure the unfettered access of some key industries (eg car manufacturing) to the single market and for deals to be struck with the rest of the world (see for example the informative statement from the City of London Corporation). Special negotiations will be needed to clarify the position in Scotland and Northern Ireland. In any event, all relevant businesses, workers and organisations should know well in advance if they are to lose their EU rights and prepare for change. The problem is that there is no time for any of these things to be achieved.

A great deal of the legal commentary so far has focused on the power of the Government to give notification of withdrawal. The process, regulated by Article 50 of the TEU, envisages that a withdrawal agreement ought to be concluded within two year from that notification. If it is not, and if the member states do not, unanimously, decide to extend that period, then the UK will be automatically out of the EU. The question whether the notification needs parliamentary approval or not was heard at a three-day hearing at the High Court a few days ago. A decision is currently imminent.

Nevertheless, this discussion has obscured another more important point. Withdrawal, with an agreement or without, is only one piece of the puzzle. It is not the most important. The key to Brexit is the agreement between the UK and the EU after withdrawal, setting out their future trade relations. This ‘trade agreement’ will determine if London banks can do business in the EU, whether British cars will be subject to customs formalities and tariffs, or whether persons will need visas to travel and work in Europe. Such issues will not be resolved by the withdrawal agreement envisaged by Article 50. The trade agreement is a separate agreement to the withdrawal agreement. It is made by a different process and has different content.

The trade agreement, for example, requires unanimity, not majority support, as provided for the withdrawal agreement in Article 50. If the trade agreement includes services – which it must, if it is to protect the ‘passport’ rights of the London financial institutions, it will be a ‘mixed’ agreement, covering ground that goes outside the exclusive competence on external trade enjoyed by the EU. It will therefore also require ratification by national parliaments of the 27 remaining member states of the EU. This takes a lot of time and has uncertain outcomes (as shown by the Canadian trade deal debacle with Belgium). While the trade agreement could (under the treaties) take effect even before it is fully ratified, it is highly unlikely that it will be concluded within two years, at least judging from the experience of similar deals with other third countries.

The distinction between the withdrawal agreement and the trade agreement has been obscured by the assumption – or, rather, the hope – that the two will be concluded simultaneously and will in practice be taken to be the same thing. But there is no guarantee that they will be concluded at the same time. Quite the contrary: it is near impossible that they will be so concluded, given the UK government’s recent pronouncements.

If they cannot be concluded at the same time, then withdrawal will take place without any trade deal at all. It can happen either through the conclusion (by majority in the Council and the consent of the European Parliament) of the withdrawal agreement under Article 50, or through the automatic exit at the end of the two years in the event that an agreement is not reached. This is what is likely to happen in the spring of 2019. But if withdrawal happens without a trade agreement in place, then the minimum WTO rules will apply at once.

Is a temporary agreement bridging the gap between withdrawal and a new trade deal a realistic prospect? It is not, for legal reasons. Having the UK enter the EEA for a temporary period of time will require the UK and the EU concluding treaties with themselves and with all the members of the EEA. This would require ratification by all parties. Negotiating, signing and ratifying such an agreement cannot realistically be done within two years.

Could, instead, the UK’s membership be scaled down for a transitional period? This would require amending the EU treaties, which is politically impossible, and in any event requires ratification by all member states of the EU, a process that also will take longer than two years. Such a treaty, by the way, would clearly engage the EU Act 2011 in the UK, which requires a referendum before an EU treaty amendment is ratified – so would require a second referendum on Brexit, which the government does not seem to want. So, given the nature of the UK’s treaty obligations, a temporary arrangement seems to me as difficult to conclude as any permanent one.

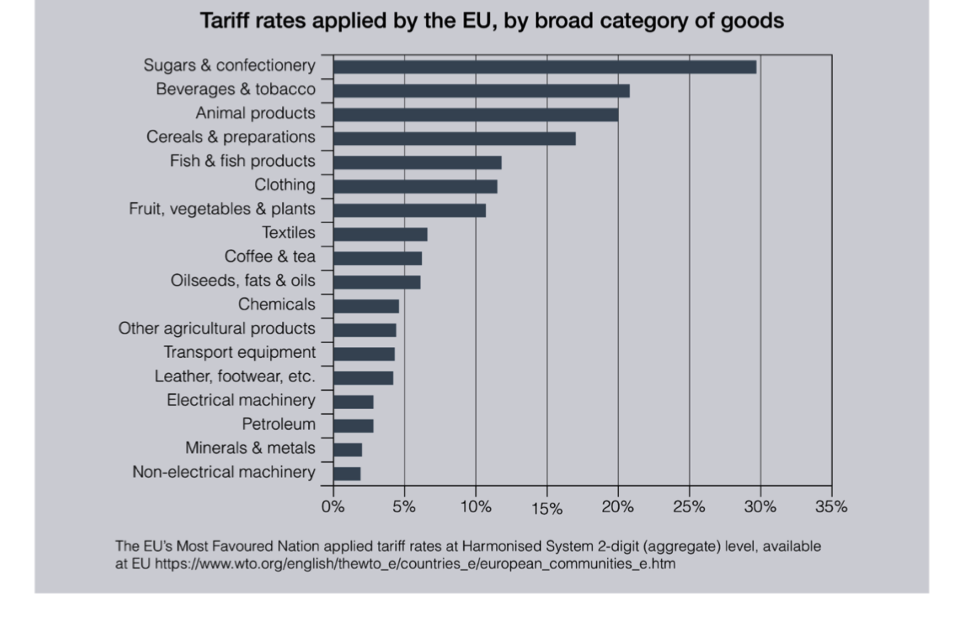

In the absence of a temporary arrangement or a permanent trade deal, the UK will thus exit the single market at once. The relevant tariffs under that WTO framework were collected by the UK government in the chart below (prepared in the course of the Referendum campaign):

The political aspect of the process is unpredictable, but it is likely that a blame game will start on both sides. The UK government will blame the EU for holding it hostage and causing hardship out of vindictiveness. EU leaders will reciprocate by saying ‘we told you so’. Anti-EU fever in the UK will rise in direct proportion to the economic hardship caused by the loss of access to the single market. Nationalism will deliver electoral success to the most populist ticket, either with Mrs May or another anti-EU leader in the 2020 general election. This is unlikely to be the start of a smooth process. This is, I think, what a failed Brexit looks like. It will be a time of rising anger, economic uncertainty, intense hardship and political instability.

For the unravelling to be avoided, we need a smooth transition to the new trade regime. But the reality is that it could only happen if the UK was ready to accept an extension of time. Negotiations must last longer if the trade agreement is to be ready at the point of withdrawal. Is this politically possible? In Mrs May’s thinking, it seems not. The Prime Minister has said - inexplicably, since she supported ‘Remain’ herself - that exiting the EU is a way for the UK to regain its ‘sovereignty’. It is now a matter of great principle. She has stressed that everything needs to happen quickly, so as not to compromise the ‘democratic will’ of the British people. Withdrawal seems set for 2019 – a year before the general election.

This is then how Brexit will fail. Either through panic, or though inertia, or through incompetence, the UK will leave the EU exactly two years after giving notification. There will be no temporary deal, no permanent trade deal and no indication of a likelihood of such a deal. The UK will leave the single market quickly, without any period of transition, without giving anyone time to adjust, and without the hope of return.

Pavlos Eleftheriadis is a fellow in law at Mansfield College, Oxford and a barrister at Francis Taylor Building.