Guest post by Sigrid Corry. Sigrid Corry is a PhD student at the London School of Economics, Department of Sociology.

What the policy tourists should find in Denmark is not a ready fix for immigration but a warning of the perils of appeasing far-right rhetoric.

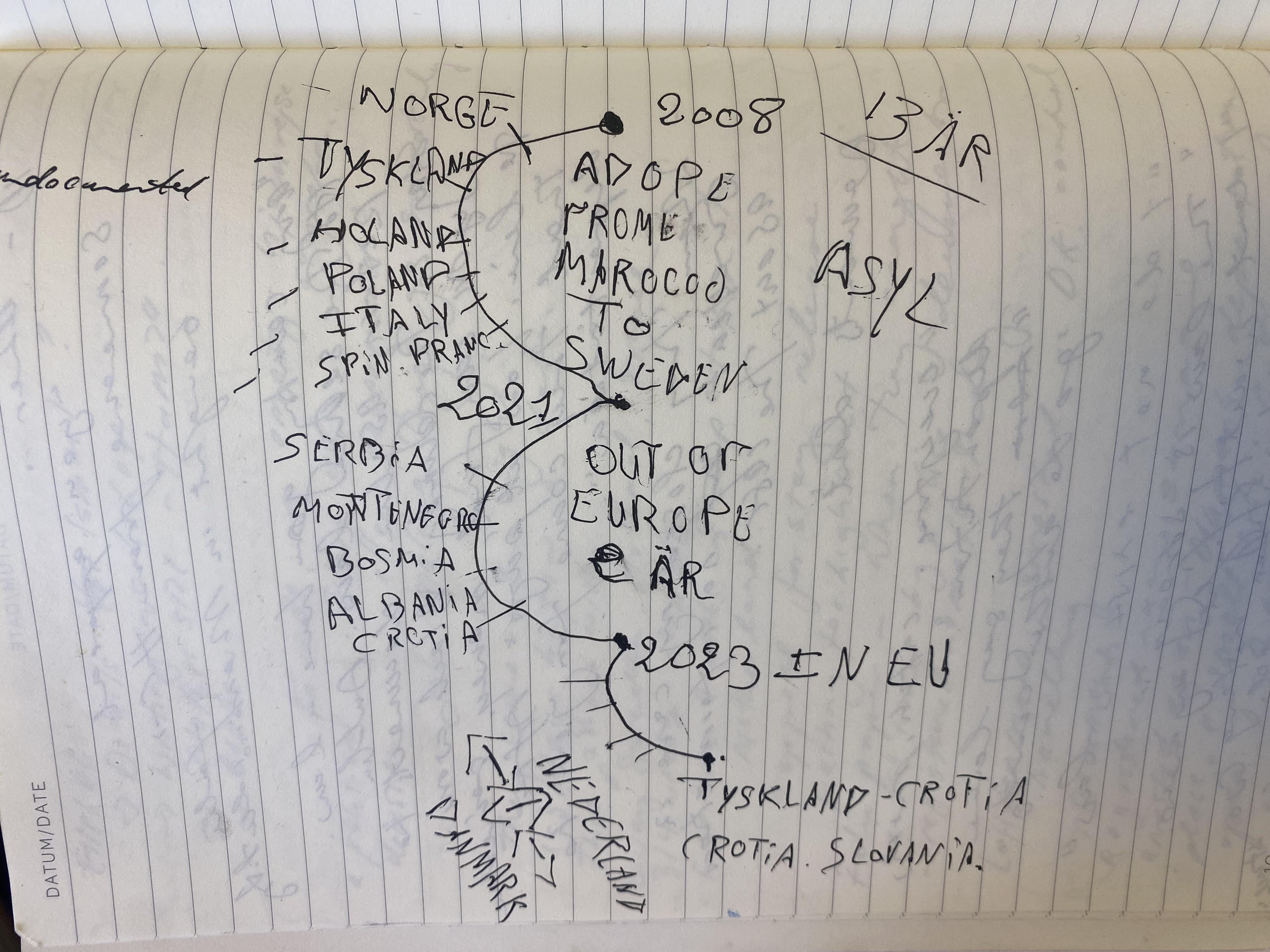

“They kill us with paper here”, Aziz*, a Kurdish-Iranian asylum-seeker told me as we walked through the Danish deportation camp, Kærshovedgård. He had been contained in the camp for ten years, after his asylum claim was rejected in 2015. He lived here, apart from his wife and young child, because the centre's regulations meant he had to register there several times per week and abide by nighttime curfews. Not keeping to these meant fines and imprisonment.

Set up by the Social Democratic government in 2015-6 to make deportations “more efficient”, the camps instead function as open prisons. They hold hundreds of people in conditions of prolonged detention, sometimes for years. Denied access to work, education, and adequate health care, they are subjected to a criminalising set of “motivational measures”. The aim of them is to apply pressure and manufacture “voluntary returns”. Meanwhile, Denmark’s immigration detention centre, Ellebæk, is deemed to be amongst the most inhumane in Europe. Migrants, including victims of torture, are detained here for up to 18 months, working for 6 DKK (80 cents) per hour. Outside the camps, the threat of deportation looms in the form of short-term protections and precarious residency for refugees and migrants.

These are the grim realities behind the model the UK now seeks to emulate. Shabana Mahmood, the UK Home Secretary, promised to do “whatever it takes to secure our borders”. According to the Labour government, the so-called ‘Danish model’ offers a restrictive blueprint implemented by a left-leaning government that can soothe anger and stem the tide of far-right parties. Labour set out reforms for “Restoring Order and Control” framing measures aimed at stopping “illegal migrants” as protecting minorities, restoring social cohesion and mending the social contract. The proposals include extending the qualifying period for indefinite Leave to Remain from 5 to 20 years and making refugee status temporary. Only with “secure borders” can “positive race relations” exist and the threat of the far-right be countered, Mahmood claimed, simultaneously promising an asylum system that is “fair, effective and humane”.

Except the Danish model has neither countered the far-right nor created anything resembling a humane, fair or effective asylum system.

Attempts to appease the far-right have effectively mainstreamed their ideas continuously since the 1990s. Taking inspiration partly from Australia’s offshore detention model, Denmark has built a reputation as an unattractive destination. A ‘deterrence approach’ has the express aim of achieving “zero asylum” applications. This is accompanied by strict family reunification laws, temporary protections and long qualifying periods for permanent residency or citizenship. Meanwhile, ‘ghetto laws’ target “non-Western” communities - a term used in official policy - with evictions and policing.

Often regarded as an egalitarian welfare state, Denmark has amongst the most restrictive immigration systems in Europe. In 2024, just 860 people were granted asylum, though a temporary protection scheme provided permits to 10,000 Ukrainians. These are omitted from the official asylum figures touted by admirers of Denmark’s restrictive regime. In addition, the total number of residency permits granted has risen from a recent low of 58,000 in 2020, to almost 100,000 in 2024, but only a small fraction are refugees and asylum seekers. Since 2015, Denmark has resettled only a few of its 500 UN quota refugees, and very few now receive humanitarian protections. Asylum applications remain low: in 2021, Sweden and Germany received six times more applications per capita. But despite its punitive system of camps, Danish deportation rates are not higher than its neighbours. Meanwhile, while a law passed in 2021 allows a full externalisation of asylum processing, nothing has come of Danish plans for this in Rwanda.

These policies do not appear to have ‘protected cohesion’ or created safety in Denmark. The so-called ‘new paradigm’ of granting only temporary asylum and precarious protection adopted in 2015, has now been accompanied by a rising chorus of calls for ‘remigration’. Structural discrimination in the welfare system, and the scapegoating of Muslims and migrant populations in Danish politics remains rife. Like the UK, Denmark is exploring ways to amend human rights commitments to enable more deportations. Mahmood's assertion that fewer migrants and tighter controls will create better protections is hardly confirmed by the Danish case.

Neither have restrictive policies achieved the aim of quelling support for the far-right. Instead four far-right parties now exist and explicitly anti-Muslim parties polled over 22 percent in the last election. Far from neutralising them, Social Democrats and centre-right politicians have kept them central to political debate, with escalating anti-immigrant politics and draconian agendas. One Social Democratic spokesperson recently suggested that even ‘well-integrated’ Muslims speaking fluent Danish, paying tax and participating in local communities are effectively ‘infiltrators’ into Danish society - operating in vocational schools, welfare state offices or even pharmacies. ‘True’ integration is achieved only through adherence to “Danish values” and mindsets, the narrative now goes.

More successful has been the export of Denmark’s rhetoric. It has consciously flaunted its anti-immigrant stance among EU governments, most recently, during Denmark’s Presidency of the European Council, when Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen — flanked by Italian far-right leader Giorgia Meloni and other EU heads of government — called for stronger EU-level immigration controls. Their joint letter warned of the risks of “parallel societies” and advocated deportation of “foreign criminals,” adopting language drawn directly from long-standing Danish political debates.

“They’ve taken the best years of my life,” Aziz told me. He would not stop speaking out until all the camps were closed, he said. Those looking to Denmark for easy answers should instead find a cautionary tale. The “Danish model” has not solved the ‘problem’ of immigration as its admirers think. What it has done is entrench the forces and narratives driving the far-right. Its most tangible results are the harms inflicted on refugees and asylum seekers. This is not a path Britain should seek to follow.

*To protect the identity of individuals pseudonyms have been used.

Any comments about this post? Get in touch with us! Send us an email, or find us on LinkedIn and BlueSky.

How to cite this blog post (Harvard style):

S. Corry. (2025) On the perils of the ‘Danish model’. Available at:https://blogs.law.ox.ac.uk/border-criminologies-blog/blog-post/2025/12/perils-danish-model. Accessed on: 07/03/2026Share: