“No Laws to Protect You”: Life Between Cyprus’ Overlapping Border Regimes

This post is part of a collaboration between Border Criminologies and Geopolitics that seeks to promote open access platforms. The full article is available here.

Posted:

Time to read:

Guest post by Seçil Dağtaş, Aicha Lariani, and Suzan Ilcan. Seçil Dağtaş, is Associate Professor of Anthropology and Religious Studies at the University of Waterloo (Canada) and a faculty member of the Balsillie School of International Affairs. Her research examines religious difference, gender relations, and the experiences of minority and displaced communities in Turkey and more recently, in Cyprus. Aicha Lariani is an MA candidate in Public Issues Anthropology program at the University of Waterloo. Her current research focuses on student migration and everyday experiences of displacement in northern part of Cyprus. Suzan Ilcan is Professor and University Research Chair in the Department of Sociology and Legal Studies at the University of Waterloo. Her research addresses critical migration and border studies, asylum policies, and community building primarily in the Republic of Cyprus. She is principal investigator of a SSHRC-funded project on borders, asylum, and resettlement in the region.

“Respect yourself, respect yourself, respect yourself. You’re in a place where you can suddenly disappear... no one knows where you are or what happened. There is no surveillance, no laws to protect you, no rules, …nothing.”

Nadeem (pseudonym), a Sudanese student, shared these words as he reflected on crossing the Green Line between the de facto Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC) and the Republic of Cyprus (RoC). We first met him during our fieldwork with students in Lefkoşa in May 2025, after one participant mentioned a friend who regularly crossed between north and south—this friend was Nadeem. During our three-hour interview, he described the forces that drive such crossings: the glossy promises of the TRNC’s higher education industry, the daily struggle to survive in an unrecognized state, the protracted waiting in RoC asylum camps, and the impossibility of returning to war-torn Sudan. “Ignorance becomes an acquaintance of one’s life,” he remarked. “You don’t know anything, you just wait. It’s a terrible feeling.”

Nadeem’s experience reflects more than personal struggle—it shows how border regimes can coalesce and collide to govern mobility across Cyprus. In our recent Geopolitics article, we call this a system of nested borders: the Green Line layers competing authorities, creating governance gaps, legal ambiguities, and spaces of exception that migrants navigate daily. Once Ottoman territory and later a British colony (with two sovereign British bases still active), Cyprus is now a non-Schengen EU member state, with over a third of its territory governed by the unrecognized TRNC. The UN-monitored Green Line cuts through this fragmented landscape, a ceasefire line turned migration frontier.

After EU crackdowns on the Balkan route in 2016, Cyprus became a new gateway to Europe. In 2023 it held the highest per-capita asylum applications in the EU. But those arriving from the north face legal limbo: the TRNC is not bound by the UN Refugee Convention, and the RoC refuses to process asylum claims in the buffer zone.

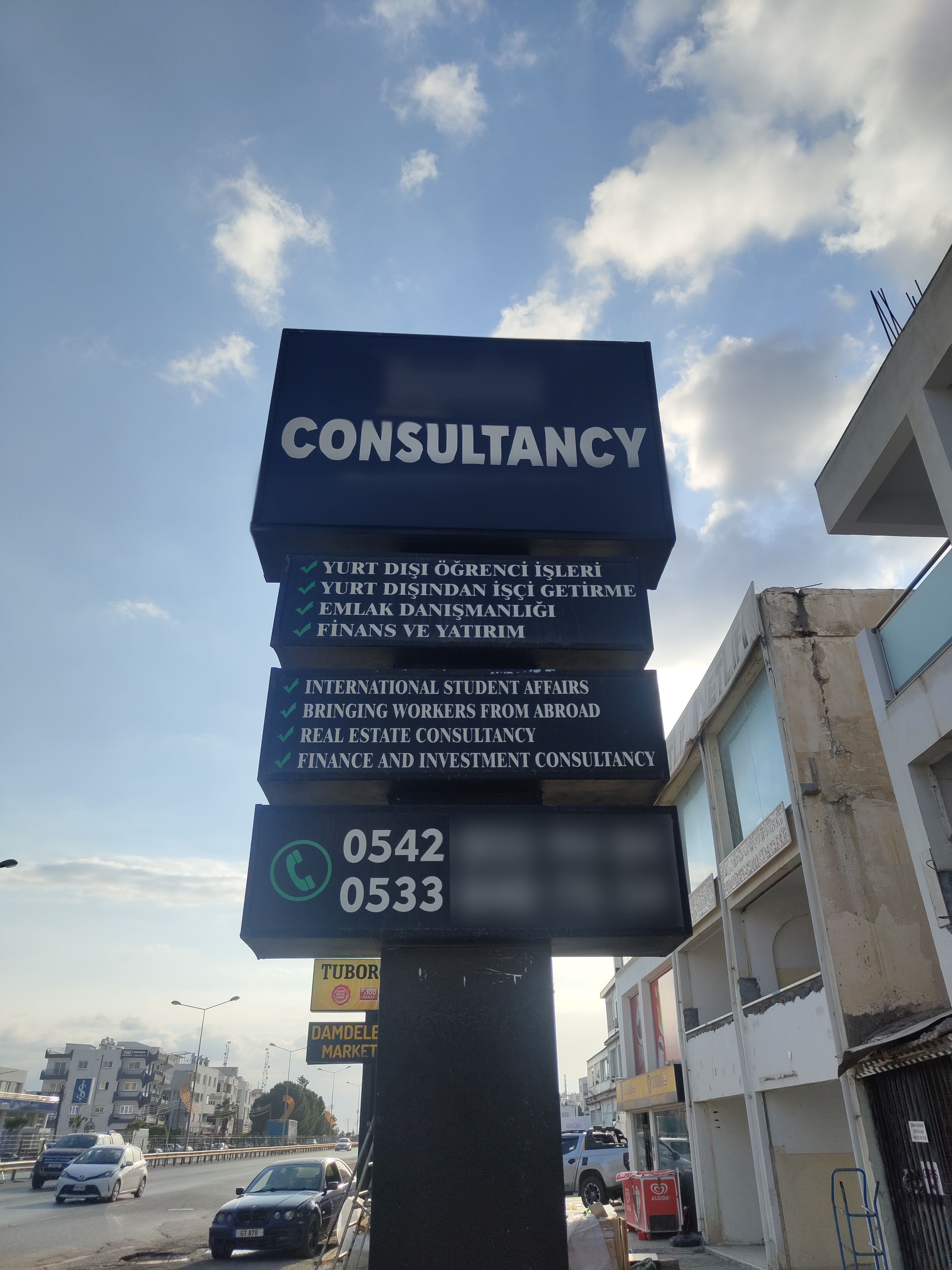

In this fractured legal and political terrain, migrants like Nadeem must negotiate survival. This post shares his story—absent from our article—to bring nested borders into sharp human focus. Nadeem’s arrival on the island began with the lure of the TRNC’s booming higher education industry. Universities there recruit aggressively across Africa and the Middle East, offering “instant admissions”, tuition reductions, and inflated scholarships. Like many other migrants, Nadeem thought he was entering the EU. Only later did he learn that his studies would take place in the unrecognized north.

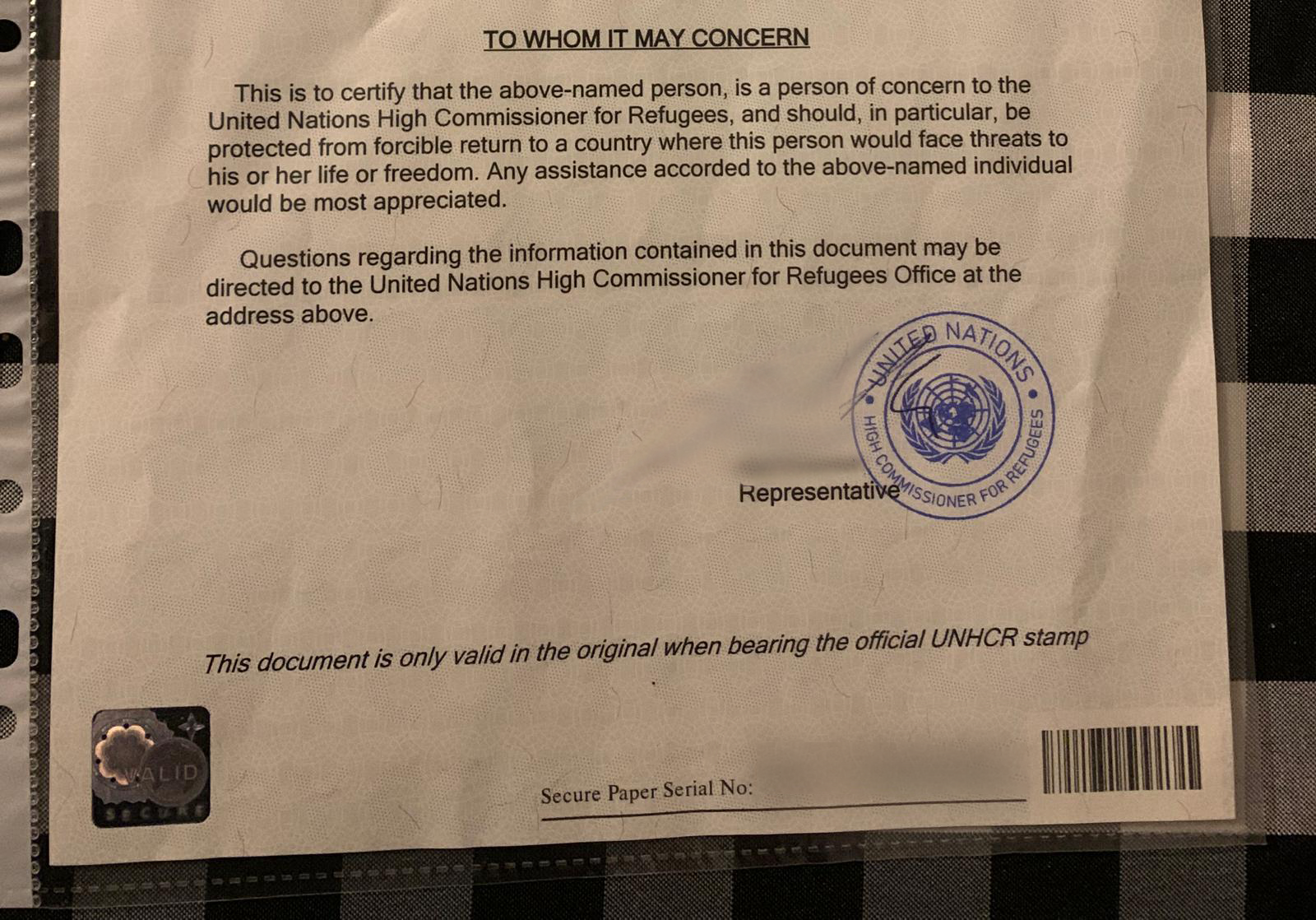

Having left Sudan just before renewed conflict, Nadeem became a de facto refugee in a place with no formal asylum protections. Local NGOs, like the Refugee Rights Association (RRA), try to fill this gap, issuing “person of concern” documents as stand-ins for UNHCR documents. But these carry little weight. Another Sudanese student who held one explained: “you can’t use it to travel… it doesn’t help with anything here.”

To survive the TRNC’s lack of work permits, non-access to legal status, and high inflation—details absent from promotional materials—Nadeem resorted to unregistered taxi driving, risking fines, harassment, and exploitation.

In an effort to gain rights and protections, Nadeem joined nine others and crossed to the south. The journey involved running long stretches on foot through trees and thorns under the scrutiny of patrol towers. The hired smugglers enforced silence, confiscated phones, and did not promise to accompany the group if stopped by RoC authorities.

At the Green Line, liminality was acute; in the RoC, it became protracted. Asylum camps resembled prisons, with long waits, no worker rights, and bureaucratic layers that left people in suspended life. Police asked questions they already knew. “The smugglers are known to authorities; it is the migrants who are the weakest link, caught in the middle” Nadeem reflected. Even international actors proved evasive. UNHCR staff redirected claims to the RoC’s asylum service, while EU officials monitored without offering recourse. Unwilling to wait, Nadeem gave a false address to leave early: “I can’t sit in a place. I feel trapped.” He witnessed others break down under confinement.

While waiting for legal status, Nadeem relied on informal work wherever available. Facing uncertain prospects, he risked returning north to continue his studies. He followed the same route, this time all alone, but was caught by Turkish patrol. They beat him with boots and rifle butts, stripped him, forced him to run under spotlights, and threatened to shoot if he strayed. Nadeem escaped and hid in the forest for several hours, nearly naked, dehydrated and exhausted. Even after reaching relative safety, he could not immediately seek medical care and tended to his injuries with friends’ help.

Nadeem’s story illustrates the human cost of nested borders, where global policies fold into the everyday and embed precarity in systems meant to offer refuge. The RoC refuses to recognize the Green Line as a border—asserting sovereignty over the entire island—yet enforces it as one through drones, patrols, deportations, and pushbacks that violate asylum law. The TRNC’s unrecognized status leaves asylum management to civil society groups, which are susceptible to political sensitivities and USAID cuts. Conversely, the dominant framings of Cyprus’s situation as “exceptional” allows the EU to sidestep deeper engagement with the island. Consequently, gaps are to be filled by humanitarian organizations, local initiatives, and faith-based groups.

To endure life between Cyprus’s overlapping border regimes, migrants take informal work, use bureaucratic loopholes, rely on friends, and sometimes take extreme risks to sustain their lives. Their crossings expose the contradictions of nested borders, recasting them as spaces not only of control but also of cracks, movement and improvisation. Nadeem continues to move between north and south, juggling studies, precarious work, and family obligations. Within borders designed to contain him, he advocates for self-respect through his choices, movements, and refusals.

As borders multiply and harden globally, Cyprus makes visible how they operate: not as simple lines separating authorities, but as nested across scales, sovereignties, and institutions. For migrants, the gaps and overlaps between these layers become the everyday terrain of survival. For scholars and policymakers, they raise urgent questions of accountability: who bears responsibility when overlapping jurisdictions create spaces where law fails, protection falters, and people are left in limbo?

Any comments about this post? Get in touch with us! Send us an email, or find us on LinkedIn and BlueSky.

How to cite this blog post (Harvard style):

S. Dağtaş, A. Lariani and Suzan Ilcan. (2025) “No Laws to Protect You”: Life Between Cyprus’ Overlapping Border Regimes. Available at:https://blogs.law.ox.ac.uk/border-criminologies-blog/blog-post/2025/10/no-laws-protect-you-life-between-cyprus-overlapping. Accessed on: 09/03/2026Keywords:

Share: