Guest post by Dr Mujib Abid. Dr Mujib Abid is a Postdoctoral Research Fellow at the University of Melbourne. He is an Afghan-Australian scholar of modern Afghan history, peace studies and political theory. Mujib’s work foregrounds critical traditions that self-locate in the Global South, including postcolonial and decolonial approaches, as well as other traditional and Islamic knowledge perspectives. One of his ongoing projects, “The Longest War: Australian Encounters with Afghanistan, 2001 to today,” studies the social and cultural dimensions of post-2001 Australian involvement in the “war on terror” and statebuilding regimes in Afghanistan. This is part one of a two part submission. You can find part two here.

Border Thinking and the Decolonial Turn

This blog post explores how Sufi-inflected writing in the Afghan diaspora – particularly poetry – serves as a form of decolonial knowledge production. In exile, Afghan writers are not simply dislocated individuals but epistemic agents working at the margins of dominant frameworks. As Afghan diasporas expand—often through involuntary displacement and racialised border regimes—so too does a transnational literary imaginary that unsettles colonial and nationalist narratives of identity, Islam, and belonging. Through the lens of Sufism, they enact what Walter Mignolo terms border thinking: knowledge born at the edge of empires, shaped by histories of displacement, resistance, and spiritual resilience.

Coined by Mignolo, border thinking refers to forms of knowing that emerge in the cracks of coloniality – knowledge shaped by movement across borders, refusal of Eurocentric epistemologies, and attention to pluriversality towards imagining alternative, decolonial futures. It draws from thinkers such as Abdelkebir Khatibi, whose notions of “an other thinking” and “double critique” insist on critiquing both Western and non-Western fundamentalisms from a position of exteriority. The fissures and cracks, on their own, as Catherine E. Walsh reminds us, are ‘not the solution but the possibility of otherwises, those present, emerging, and persistently taking form and hold.’ The aim, thus, is not merely critique, but transformation: to imagine a world beyond singular, totalising systems of thought.

Within Muslim thought, this epistemic openness finds expression in traditional Islam, particularly as articulated through Sufism. Traditional Islam, as embodied and practiced by a majority of the Muslim faithful around the world, is rooted in classical metaphysics, esoteric readings, and spiritual experience. It is a third path to the suffocating dichotomy often drawn in Western scholarship which sees Islam exclusively in political terms, a binary of Islamic modernism (“moderate Islam”) or Islamic fundamentalism (“radical Islam”). It is at once historical, intellectual, and lived.

Afghanistan’s Sufi Inheritance and its Silencing

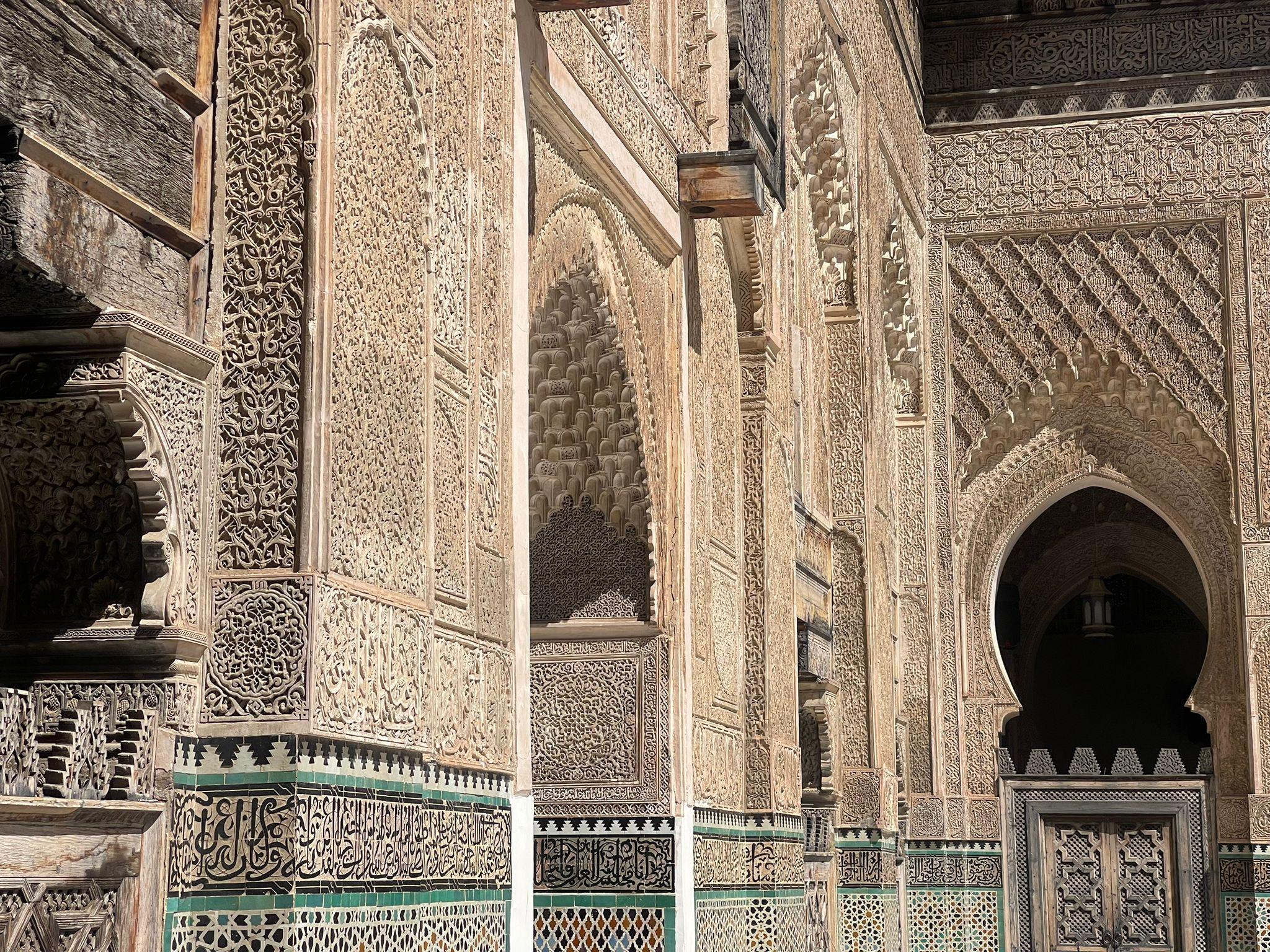

In Afghanistan, the Sufi tradition – what Seyyed Hossein Nasr theorises as the traditional Islamic current and Idries Shah has done so much to make accessible to a global audience – runs deep. For over a thousand years, tasawuf has coexisted dynamically with the dominant Hanafi jurisprudence and local customs (sunat-hai mardumi), both tribal and urban, Islamic and pre-Islamic. This cohabitation has produced a distinctive Afghan modality of Islam – esoteric, flexible, poetic, and deeply embedded within localised, non-hierarchised approaches to organisation of power.

Poetry, in particular, sits at the core of this spiritual epistemology. Afghan poetic traditions include the highly formalised Khorasani and Iraqi styles, the mystical and layered Bedil school (bedil shinasi), and diverse folk forms. As the renowned Afghan literary historian Haidari Wujudi observed, “Poetry is the glowing pearl that sheds light into every crevasse of history.”

Despite its depth and continuity, traditional Islam in Afghanistan has repeatedly come under attack – from colonial powers, from the modernising, nationalist elite, and from authoritarian regimes. Early 20th-century reformers like Mahmoud Tarzi dismissed this mode of knowledge as outdated, declaring, “The time of poetry is over. Now is the era of motor, rail, and electricity.” This techno-utopianism aligned Afghan nationalism with Eurocentric development logics, marginalising esoteric Islam in favour of scientific rationalism and bureaucratic modernity.

Later, during the April 1978 Communist “revolution”, literature itself became a terrain of state control (and that of its modernist and Islamist adversaries). As Wali Ahmadi notes, both the state and its Islamist adversaries instrumentalised intellectuals as tools of commandment. The complexity of Sufi expression – its ambiguity, inwardness, and refusal to conform – was systematically silenced.

War, Exile, and the Persistence of Poetic Knowledge

The decades of conflict that followed – Soviet occupation, civil war, Taliban rule, U.S. intervention – produced devastation and mass displacement. Over six million Afghans have been forced into exile. According to the Migration Policy Institute, more than 90% now live in neighbouring countries, while others are scattered globally. In Australia, Afghan migration dates back to the 19th-century Ghan Cameleer communities. But modern arrivals – especially post-1980s – have mostly come as refugees, often subjected to Australia’s harsh, racialising and securitised border policies.

As Border Criminologies charges, borders, in policing movement and disciplining bodies, can become sites of violence. This can be direct violence – in Australia, we can think of onshore and offshore detention camps, where, as Behrouz Boochani has poignantly pointed out, a “state of exception” is enacted such that sovereignty is extended and closed at will. But it can also be structural and cultural violence. It is structural because asylum seekers and refugees have limited access to rights, resources and opportunity, while existing vulnerabilities are exacerbated (see Segrave and Vasil on the impact of border regimes on migrant women’s safety in Australia). It is cultural because migrants are silenced, their gnosis and ontological realities entirely consumed into or systematically marginalised by an assimilationist mainstream, and yet somehow none of it feels “wrong”. A combination of this violent triad is enacted against Afghan refugee poetics and literati.

Despite this, Afghan communities in Australia continue to produce rich cultural work. As of mid-2023, over 78,000 Afghan-born people live in Australia, including thousands evacuated after the fall of Kabul in 2021. Among them are poets, musicians, journalists, and scholars – many drawing from Sufi worldviews to articulate forms of knowledge rooted in intuition, spirituality, and border thinking.

These writers often operate outside the purview of Australia’s literary mainstream. Their work, usually in Dari or Pashto, is rarely translated or published through dominant institutions. Instead, they rely on informal transnational networks: books printed in Kabul or Tehran, manuscripts couriered by relatives, poems circulated via WhatsApp or shared in virtual literary salons.

Writing from outer-suburban community spaces or private homes – often while navigating the pressures of precarity, work, and family – these poets are doubly marginal: peripheral to both their new homelands and their ancestral centres. And yet they persist.

This is a self-publishing economy, grounded in collective memory and spiritual urgency. Authors gift books, recite poems in community gatherings, and contribute to a transnational conversation that defies borders and institutions. Their work doesn’t seek to be assimilated into the mainstream cultural spaces or market-friendly narratives. It speaks laterally: to each other, across languages, generations, and geographies.

The exilic Sufi writer stands between worlds. Their knowledge is not located neatly in the past, nor fully in the future. It arises in the in-between: in the hidden meanings of scripture, in the loss of a homeland, in the intimacy of a remembered verse, in the gathering of strangers over Zoom at dawn.

This is border thinking as lived practice—neither nostalgic nor utopian, but stubbornly present. It is a refusal to surrender poetics to the realm of “what was,” and an insistence that the sacred, the beautiful, and the true still circulate in our fractured now.

Any comments about this post? Get in touch with us! Send us an email, or find us on LinkedIn and BlueSky.

How to cite this blog post (Harvard style):

Mujib Abid. (2025) Sufism in Exile as Border Thinking (Part One). Available at:https://blogs.law.ox.ac.uk/border-criminologies-blog/blog-post/2025/07/sufism-exile-border-thinking-part-one. Accessed on: 23/02/2026Keywords:

Share: