Creating the ‘lawyer of the future’ in times of disruption: the power of building a new world of on-going, workplace-focused education

Posted:

Time to read:

Creating the ‘lawyer of the future’ in times of disruption: the power of building a new world of on-going, workplace-focused education

Over the past year with partner organisation Meridian West we have carried out practitioner research to explore how disruption in the legal sector, including the increasing use of technology and AI, is impacting the talent development agenda. In particular we have explored how firms can create competitive advantage through a strategic use of Learning & Development initiatives at this time of change: designing their ‘firms of the future’, creating the capability to manage change towards these new models, and the implications of the rapid market changes on career pathways both for those entering the legal profession and also for those holding senior leadership roles.

In addition to this external, market-led disruption, driven by clients seeking greater efficiency and service quality, there are also the imminent, significant changes to the route to solicitor qualification in England & Wales with the introduction of the ‘Solicitors Qualifying Examination’.

Taken together, this fundamental shift of ‘context’ raises some challenging questions for law faculties at higher education (HE) institutions, and I presented my initial thoughts on some of these challenges – and opportunities – at the ‘kick-off’ conference for Oxford’s high-profile project “Unlocking the potential of AI for English Law” in Prof. Ewart Keep’s session on ‘The implications for Higher Education’.

Three questions for HE in preparing the ‘lawyers of the future’

First, I think there is a question of ‘purpose’ for HE. My question for HE institutions – and their law faculties – has always been: ‘What journeys are we trying to help people to make?’ Towards practice, towards deeper academic or research pathways, or towards other careers? And if approximately 50% of law graduates will be seeking to move towards practice, and 50% towards other career paths, how can any faculty or department cater for this plurality in their HE offering? Moreover, even for the 50% who are moving towards ‘practice’, this is far from a single destination now, with the wider spectrum of legal service providers each looking for different types of entry-level professionals.

Second, there is the question of how quickly the HE offering should evolve. If the external context (especially of employers in the client-driven world of private practice) is changing so rapidly, should HE be ready (and willing) to reinvent elements of the its offering at a similar pace? For example, with ‘knowledge’ being increasingly commoditised, and clients telling firms that they value a broader skill-set, are HE departments prepared to alter the balance of the time devoted to ‘knowledge’ and ‘skill development’ in the 3-4 years when students are attached to their department? And not just to change their offering once, but to evolve it regularly? Should this be a goal of HE law faculties and, if so, how does such ‘ongoing iteration’ sit within the regulatory frameworks of HE qualifications?

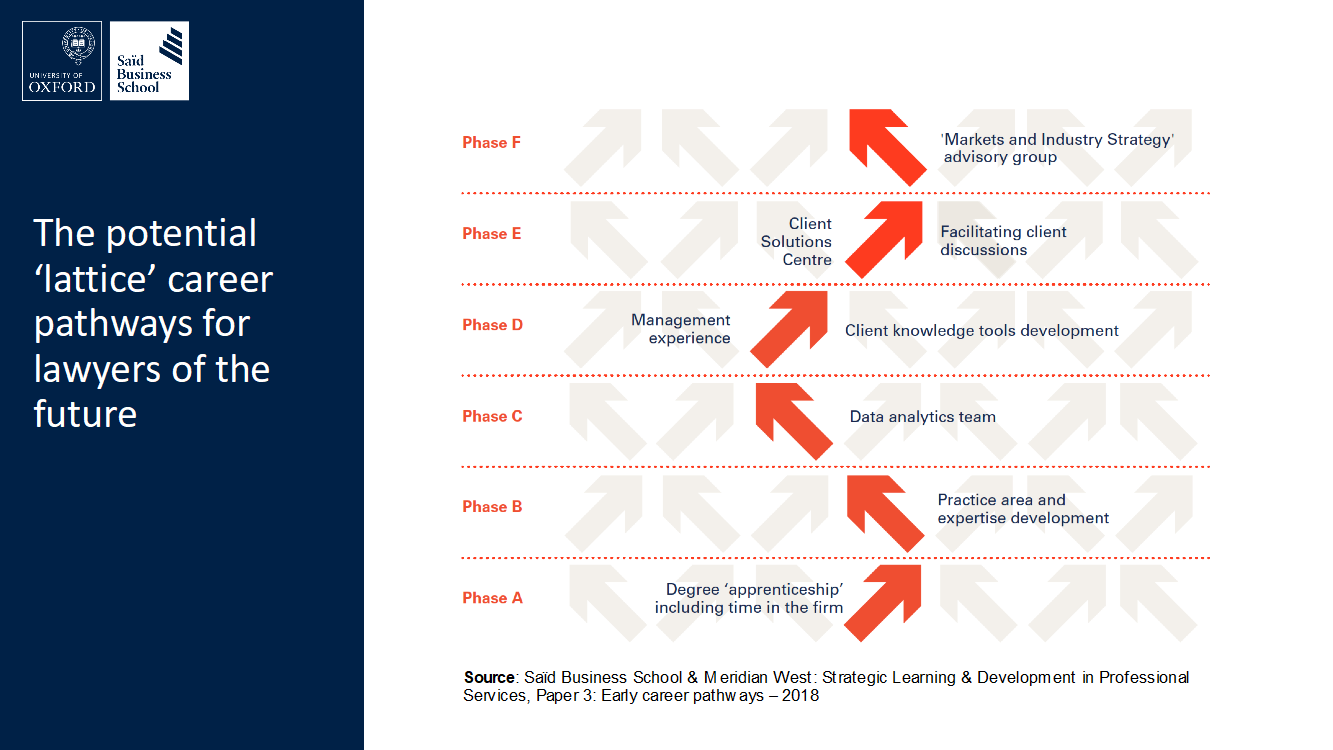

Third, as the pathways in practice change for those entering the professions, and the nature of roles in firms increases and becomes more plural (see below), HE needs to consider what is the base of knowledge (and skill) which will be needed for all pathways. For example, will there be a need for as much expertise in the early phase of a legal career as there was previously, given that clients can now access knowledge more readily, and often without charge, at the touch of a button?

For the students headed towards practice, you could summarise these challenges and questions for HE law faculties as:

- ‘Where’ … are their practice-focused law students headed: to Clifford Chance, Axiom or EY?

- ‘What’ … is the curriculum, and ‘how much expertise is enough’ for the beginning of a career?

- ‘When’ … in their careers do people need the knowledge/skill?

To give a recent, practical example, Linklaters recently announced that associates who had entered the firm through the ‘traditional’ route could now move across on a career path to the ‘tech’ part of their business.

The results of ‘dialling up’ this workplace-focused, commercial education were interesting as all stakeholders saw benefits. The graduates themselves were much more confident on entering the workplace, and also reframed their sense of identity from ‘technical specialists’ to ‘business advisors’.[5] Partners said that they had a different level of commercial conversation with these new entrants; they were more confident and client-ready. And client feedback was equally positive, including on the work they did on an MBA strategy project in their offices. In fact, the only problem we had with clients was not to rebut a ‘Deutsche Bank challenge’ about the value of having pairs of our graduates run strategy projects for them for 4 weeks but, instead, was to find enough graduates to send to them! To give just one example, one major bank which took 2 graduates on a project one year, then asked for 12 the next year to work on 6 different projects, such was the value-perception of graduates with enhanced commercial learning.

From these practical experiments I have carried out over many years, together with our recent research which indicates how legal career paths are becoming more ‘plural’ and varied, two future strategies for HE stand out for me.

Methods for future HE (1): continue to ‘collapse the distance between HE and the world of work’

First, it has crystallised in my mind that one urgent need to prepare law students effectively for practice is to continue to ‘collapse the distance between HE and the world of work’. In other words, for students seeking a career pathway towards practice, we need to create much more time during their time in HE for ‘learn by doing’ opportunities to carry out practical, ‘personal learning experiments’ where they have responsibility for applying their knowledge in workplaces. Experiences such as the ‘year in industry’ we created with Queen Mary University of London’s ‘LLB Law in Practice’ degree,[6] or Exeter University’s innovative work in creating a ‘virtual law firm’ in their Law School where students would manage their own firm,[7] are creative experiments which could all be expanded.

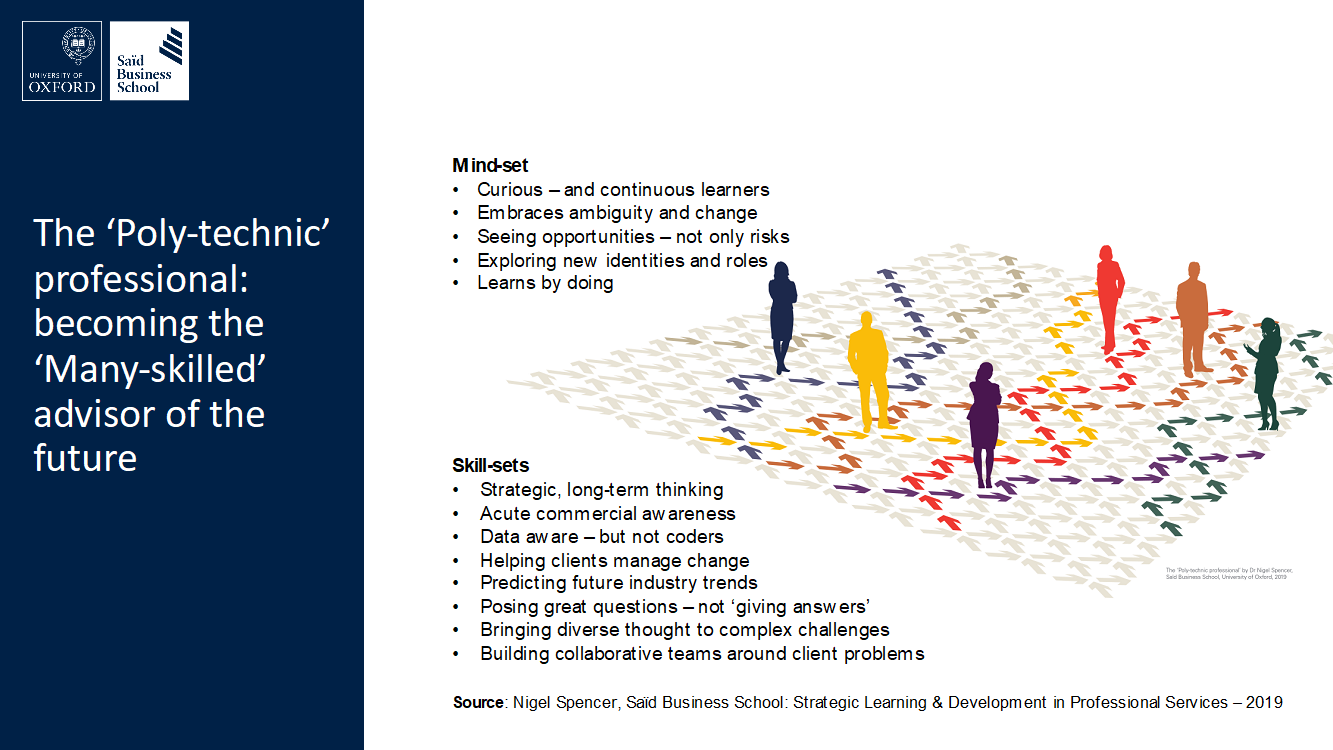

For HE, these practical, more ‘poly-technic’ approaches can have multiple benefits for all stakeholders.

For students starting out, such practical opportunities will be a more sure-footed guide on their different career journeys. Not only will they allow students to understand through actual experience the potential ‘fit’ of their various, imagined future career pathways ahead. In addition, in a legal sector where those now entering the profession will need to reinvent themselves many times over their career, this practical, experience-led approach will enable easier shifts in identity.[8]

For HE institutions themselves, such approaches, with practical projects outside the campus, can also allow HE to connect more with the sense of purpose which students seek, and to establish a greater ‘sense of place’ for universities, connecting them more strongly with the communities in which they are situated.[9]

Methods for future HE (2): on-going learning and micro-qualifications

Second, as career paths and roles in legal service providers become more emergent (it is hard to imagine, for example, what all the roles might be even in 3-5 years’ time), those building their careers in this environment will need to be iterative, ongoing learners. A career will no longer be periods of ‘education’ - ‘work’ - ‘retirement’. Instead, it will be more a pattern of ‘education’ - ‘initial role/career’ - ‘education’/re-tooling for next role - ‘education’/re-tooling for subsequent role.

In such a model, HE can consider what role – and where – it wants to play. Does a future relationship between an individual and their chosen HE provider (public sector or private) look more like an ongoing membership across a career, with access to a pool of inter-disciplinary learning resources (the ‘personal learning cloud’ which is increasingly spoken about[10]) and micro-qualifications to upskill them for their next role? Or is that ‘ongoing learning’ role still to be played by internal Learning & Development functions, or by industry sector membership bodies which have historically provided initial qualifications?

In other words, the choice (and opportunity) for HE could be to expand its touchpoint – and revenue streams – with professionals from a period of 4 years to 40 years.

Dr Nigel Spencer

12 April 2019

[1] A. Messios, ‘Linklaters begins moving associates into permanent tech roles: the firm is looking for tech savvy associates to leave the partner track and work on its ambitious AI project’ (Legal Week, January 17 2019).

[2] N. Kaminski, ‘Forty STEM students headed to Reed Smith’s Innovation Hub to tackle a data problem’ (Legal Cheek 8 December 2017): https://www.legalcheek.com/lc-careers-posts/forty-stem-students-headed-to-reed-smiths-innovation-hub-to-tackle-a-data-problem/ [Accessed online 11 April 2019].

[3] The concept of ‘polytechnics’ derives from the Greek words ‘poly’ (‘πολύ’, ‘many’) and ‘technē’ (‘τέχνη’, ‘skill’).

[4] A. Ward and A. Berry, ‘Deutsche Bank to refuse to pay for trainees and NQ lawyers after panel overhaul’ (Legal Week, 21 March 2017).

[5] N Spencer and L Crittenden, ‘Case study: Reed Smith LLP – Innovating to create a ‘commercial mind-set’ in graduate lawyers by evolving the Legal Practice Course into a Business Masters programme’, pp. 75-80, in P. McMullan, Trainee recruitment and management: a definitive law firm guide (ARK Group, 2013). See the bar charts on p. 80 indicating the change in mind-set of the graduates during the course towards their perception of their future ‘City lawyer’ role being as rounded business adviser.

[6] T. Moore, ‘Routes into law: Queen Mary teams up with Reed Smith on ‘degree with apprenticeship in law’‘ (Legal Business, 13 January 2015) https://www.legalbusiness.co.uk/blogs/routes-into-law-queen-mary-teams-up-with-reed-smith-on-degree-with-apprenticeship-in-law/ [Accessed online 11 April 2019].

[7] See the blog ‘Virtual law firm of the year’ reporting the initiative https://www.michelmores.com/news-views/news/virtual-law-firm-year [Accessed online 11 April 2019].

[8] For the importance of practical experimentation in career steps to continually evolve one’s identity see H. Ibarra, Working identity: unconventional strategies for reinventing your career (Harvard, 2003).

[9] See G. Mulgan, ‘Challenge-driven universities to solve global problems’ (nesta, 10 predictions for 2016) https://www.nesta.org.uk/feature/10-predictions-2016/challenge-driven-universities-to-solve-global-problems/ [Accessed online 11 April 2019].

[10] For the ‘personal learning cloud’, see most recently M. Moldoveanu & D. Narayandas, ‘The future of leadership development’ (HBR, 2019).

Share: