Why take a gender-based approach to the death penalty for drug trafficking?

Posted:

Time to read:

On World Day Against the Death Penalty 2018, the UN Special Rapporteur on extrajudicial, summary or arbitrary executions, Agnes Callamard, announced the prioritisation of a ‘gender-based’ approach to capital punishment. This announcement coincided with the publication of the Cornell University Center on the Death Penalty Worldwide’s report, Judged For More Than Her Crime: A Global Overview of the Women Facing the Death Penalty – the first systematic examination of the issue of gender and capital punishment – which found that of the approximately 500 women on death row worldwide, many are victims of gender-based discrimination and have faced, and continue to face, various forms of oppression.

Around this time, I began my doctoral research into the experiences of women sentenced to death for drug trafficking in Malaysia, and I benefited from the momentum established by Cornell’s report. However, as I began conducting my interviews with stakeholders involved in the women’s cases – including lawyers, NGO activists, consular officials, judges, prosecutors and police – I encountered some resistance to my research topic. Several of my interviewees mentioned that they did not really see this as a ‘gender issue’ – indeed, the majority of those on death row in Malaysia (and around the world) are men. There was a concern that by focusing on women this would detract attention away from the expansive male death row, or, worse yet, that retentionist governments (such as the Malaysian government) might champion the cause of women on death row (‘low-hanging fruit’) in an effort to appease the UN and other abolitionist groups, whilst avoiding making any meaningful change.

Furthermore, as I began discussing my research topic – women on death row for the crime of drug trafficking – some of my interviewees, especially the lawyers I spoke with, were perplexed about the ‘gender dimension’ to this crime, as there are many more men than women on death row for drug trafficking in Malaysia. Moreover, if we were focusing on the crime of homicide, it would be easier to chart the causal relationship between gender-based discrimination and the ensuing crime, for example, as has been shown by other research from the DPRU in conjunction with the Death Penalty Project, which focused on women on death row in Ghana and Sierra Leone who were survivors of domestic abuse and were convicted of killing their abusers, otherwise known as ‘battered women syndrome’.

So, what are the gendered dimensions of women on death row for drug trafficking? Well, since its inception in the 1960s and 70s, feminist criminological theorising has shown that women commit crimes – and are criminalised – for gender-specific reasons, often related to their position in patriarchal society (see, for example, the seminal work of scholar Beth Richie). And, the death penalty aside, over the past few decades we have witnessed a marked increase in the number of women incarcerated worldwide (e.g. the female prison population grew by 59% globally between 2000 to 2020), which has largely been attributed to the over-incarceration of women for low-level drug offences. Much of the existing research on women and drug trafficking has highlighted that women – predominantly from the global South – engage in drug smuggling for economic reasons as a result of neoliberal reforms and the ‘feminisation of poverty’.

If we take the specific case of Malaysia, it is helpful to look at a break-down of the statistics on the death row population: according to figures from Amnesty International, in 2019 there were 1,140 men and 141 women on death row in Malaysia. Whilst there is a higher number of men on death row than women, it is important to note that:

- A higher proportion of women are sentenced to death for drug trafficking (95% as compared to 70% of the male death row); and

- A higher proportion of women on death row are foreign nationals (86% of the female death row population and only 39% of the male death row population).

So, what is behind the disproportionately high number of foreign national women on death row for drug trafficking in Malaysia? Many of the women are from other countries in the global South, such as Indonesia, the Philippines, Iran, China and Thailand, and I link this trend to the ‘feminisation of migration’ in the region, where, again owing to neoliberal economic reforms in the latter part of the twentieth century, women have migrated to work abroad in feminised industries. And indeed, findings from my empirical data suggest that many of the women were working in feminised fields such as domestic work and within massage parlours, and agreed to courier drugs, or were duped into doing so, in the course of travelling for their work. Other criminological research has also focused on the criminalisation of female migrant domestic workers in Asia.

As part of my research I reviewed court testimonies and found that many of the women’s defences centred around the role that a male intimate partner played in duping them into couriering drugs, in some cases through online romance scams. Reports have emerged from the region of drug syndicates targeting women specifically in this way. My data also show that women engaged in drug couriering (many claimed they did not know it was drugs they were carrying, but thought they were being paid to carry items such as clothing and electronic goods) for other, gendered reasons, such as to make ‘quick money’ as single mothers to support their children or to pay for family members’ medical bills. Overall, I argue that women engage (knowingly or unknowingly) in drug couriering for money as a consequence of gendered economic precarity – more on this, here.

Moreover, once intercepted and charged, I found that women were often held to different standards in court. My review of judgments (from the High Court, Court of Appeal and the Federal Court of Malaysia) found that judges had in mind a paternalistic stereotype of a vulnerable, uneducated female dupe who was deserving of mercy, but dismissed the defences of those who did not fit this role. This is evidenced in the following quotations from judges:

We are of the considered view that it is very unlikely that the respondent, who is a diploma holder… could have placed herself in a situation where she could be exploited to commit a crime.

Her handbag contained make-up, ladies’ accessories, a Gucci watch, sunglasses and a wallet containing American dollars… These items are not a poor lady’s possession, but the items indicate she is a socialiser – a lady of the ‘world’.

Overall, therefore, my research findings from Malaysia demonstrate that gender is indeed a significant variable to consider when researching capital punishment. It is important to consider the gendered drivers behind women’s involvement in capital crimes, as well as to examine the differential treatment of female offenders in death penalty trials and appeals. The death penalty – like the rest of the criminal justice system – is not gender-blind.

Lucy Harry is a DPhil Candidate at the University of Oxford Centre for Criminology and Death Penalty Research Unit.

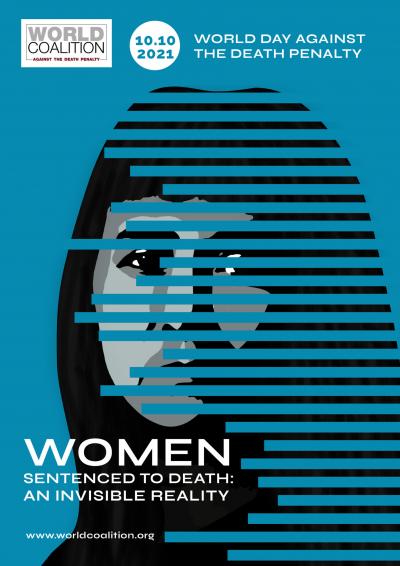

The World Day Against the Death Penalty 2021, held on 10 October, focused on the theme 'Women and the death penalty: An invisible reality'. For further details about the World Day, see the World Coalition Against the Death Penalty website here.

Share: