This post presents reflections on the key messages from Amnesty International’s latest annual global report on the death penalty, Death Sentences and Executions 2020, which was published on 21 April 2021.

The use of the death penalty further declined in 2020, with the number of recorded executions decreasing by 26% compared to 2019 and reaching, for the third consecutive year, the lowest level of executions recorded by Amnesty International in a decade. The number of new death sentences known to have been imposed in 2020 decreased by 36% compared to 2019.

Developments from 2020 further confirmed that the world is making continuous progress towards the abolition of the death penalty. The trend was evidenced by the abolition of the death penalty for all crimes in Chad in May of 2020; Kazakhstan signing and taking steps to ratify the Second Optional Protocol to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, and the fact that no executions were recorded in Bahrain, Belarus, Japan, Pakistan or Sudan, all countries which carried out executions in 2019.

This downward trend reflects a significant reduction in executions in some retentionist countries and, to a lesser extent, some hiatuses in executions that occurred in response to the Covid-19 pandemic.

While this trend in recorded executions is certainly to be welcomed, access to the full data about executions is limited in a number of countries. The number of executions carried out in China, North Korea and Viet Nam, all countries which are believed to extensively resort to the death penalty, are for instance not known publicly. China alone is believed to execute thousands of people each year, making it the world’s most prolific executioner ahead of Iran (at least 246), Egypt (at least 107), Iraq (at least 45) and Saudi Arabia (27). These last four countries alone accounted for 88% of all known executions in 2020.

Carrying out executions in a pandemic

As the world fought to protect lives from Covid-19 in 2020, 18 countries took lives using the death penalty.

Egypt more than tripled its annual rate of recorded executions, becoming the world’s third most frequent executioner in 2020. The US resumed federal executions after a 17-year hiatus and put a staggering 10 people to death within six months. India, Oman, Qatar and Taiwan also went against the global trend of abolition of the death penalty by resuming state killings. China announced a crackdown on “criminal acts” affecting Covid-19 prevention efforts, which resulted in at least one man being sentenced to death and executed.

In several countries, Covid-19 restrictions further worsened the situation, notably by impeding access to legal counsel and other critical fair trial guarantees, exacerbating the inherent cruelty of the punishment.

Fighting a death sentence is hard and doing so in the midst of a pandemic is even harder. Appeals processes, support for inmates on death row and access to prisons with high risk of exposure to Covid-19 have been impacted significantly throughout 2020.

Death penalty in violation of international law

The death penalty continued to be used in ways that violated international law and standards in 2020. For example, Iran used the death penalty after grossly unfair trials, and executed three people who were under the age of 18 at the time of the crime for which they had been convicted. Although recorded executions in Iran continued to be lower than in previous years, the country increasingly used the death penalty as a weapon of political repression against dissidents, protesters and members of ethnic minority groups.

Death sentences were known to have been imposed after proceedings that did not meet international fair trial standards, including based on “confessions” that may have been extracted through torture or other ill-treatment, in countries such as Egypt, Iran and Saudi Arabia. In Bangladesh, Democratic Republic of Congo and Palestine (State of) death sentences were imposed without the defendant being present (in absentia). US federal authorities proceeded with executions by lethal injection after the original death warrant had expired, despite the fact that motions were pending before the courts.

People with mental (psycho-social) or intellectual disabilities were known to be under sentence of death in several countries, including Japan, Maldives, Pakistan and USA.

In a number of countries, the death penalty was used for crimes that did not involve intentional killing, and therefore did not meet the threshold of “most serious crimes” under international law, including drug-related offences (China, Indonesia, Iran, Laos, Malaysia, Saudi Arabia, Singapore, Sri Lanka, Thailand, Viet Nam), economic crimes (China, Viet Nam), blasphemy (Nigeria, Pakistan) and rape (Egypt, India, Iran).

Time to abolish the death penalty

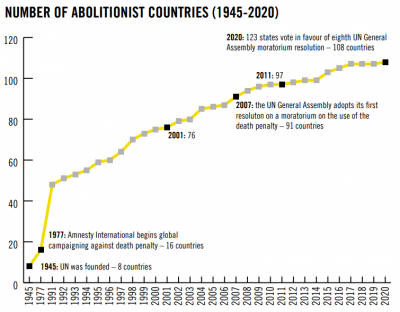

While some governments persist in using the death penalty, the overall trend remains: the world is moving away from it. With a record 123 states in 2020 supporting the biennial resolution of the UN General Assembly for a moratorium on executions, the momentum keeps growing. And while the Covid-19 pandemic played a certain role in the reduction of executions carried out and death sentences imposed, the figures recorded in 2020 provided further evidence of the global trend towards abolition – 2021 must not be the year of regression.

The remaining outliers must end judicial executions for good and join those resolute to consign the ultimate cruel, inhuman and degrading punishment to the history books. With partners around the world, Amnesty International will continue its campaign against the death penalty until it is abolished everywhere, once and for all.

The full report can be read on the Amnesty International website: Death Sentences and Executions 2020

Ula Dzudzewicz is a Paralegal at Amnesty International’s International Secretariat. She works in the Strategic Litigation Unit, which supports the movement’s human rights litigation, and in the organization’s Legal Department. She assisted the Death Penalty team with the 2020 Death Sentences and Executions Report. Ula holds a First-Class Bachelor of Arts Degree in Politics and Human Rights from the University of Essex and an LLM Qualifying Law Degree from BPP University in London.

Share: