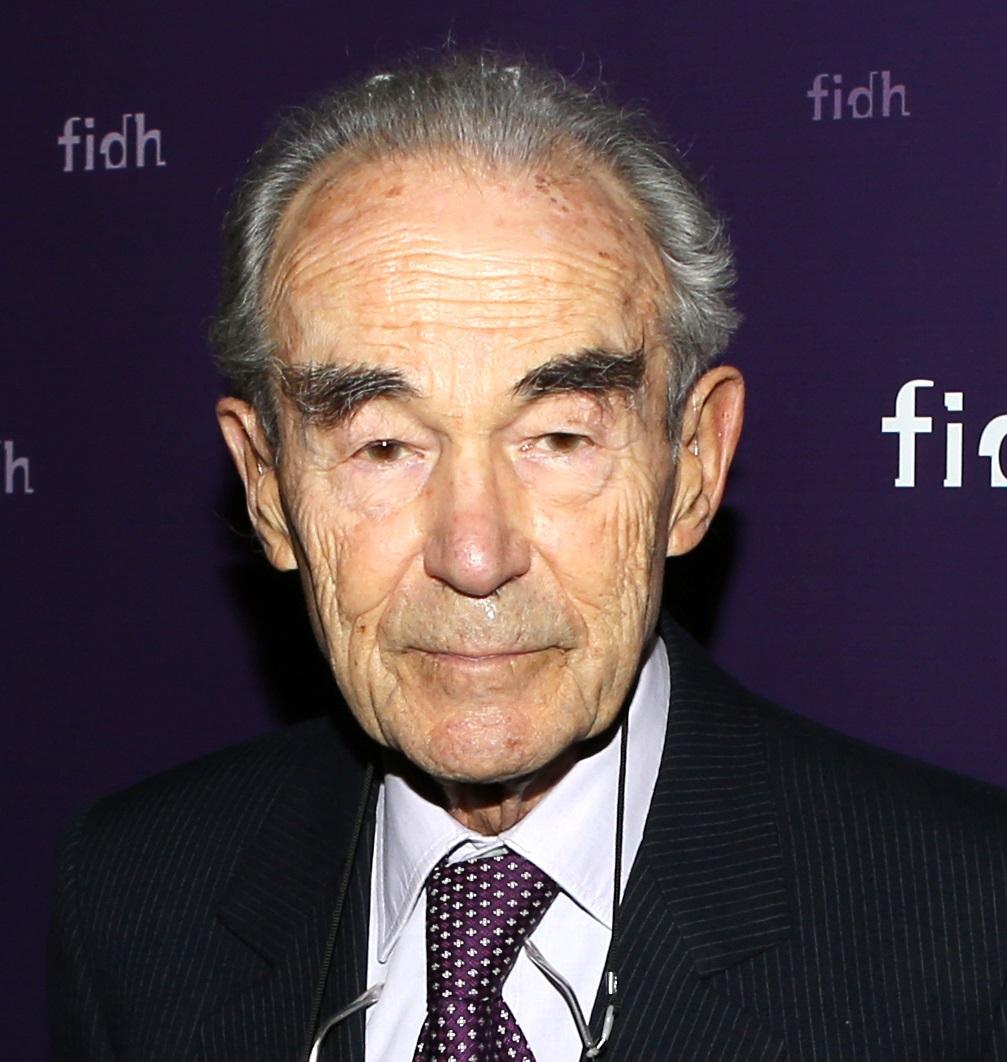

Today – February 14, 2024 – Paris hosted a memorial service for Robert Badinter (1928-2024), the lawyer and socialist politician. Following his death at the age of 95, it seems to be an appropriate time to reflect on his contribution to the abolition of the death penalty, not only in France but globally – above all his conviction that it is possible for democracies to achieve a broad measure of consent for abolition, even when it is widely believed that a majority of the public are in favour of retention. Badinter, who served as justice minister in the government led by Francois Mitterand, sensed this instinctively, through his well-developed political antennae. Recent empirical research by the Death Penalty Research Unit (DPRU) and our partners, the Death Penalty Project in London, and human rights organisations in Africa and Asia has come to the same conclusion – and helped to speed abolition in jurisdictions including Sierra Leone and Ghana, where we have shared our research findings.

Today – February 14, 2024 – Paris hosted a memorial service for Robert Badinter (1928-2024), the lawyer and socialist politician. Following his death at the age of 95, it seems to be an appropriate time to reflect on his contribution to the abolition of the death penalty, not only in France but globally – above all his conviction that it is possible for democracies to achieve a broad measure of consent for abolition, even when it is widely believed that a majority of the public are in favour of retention. Badinter, who served as justice minister in the government led by Francois Mitterand, sensed this instinctively, through his well-developed political antennae. Recent empirical research by the Death Penalty Research Unit (DPRU) and our partners, the Death Penalty Project in London, and human rights organisations in Africa and Asia has come to the same conclusion – and helped to speed abolition in jurisdictions including Sierra Leone and Ghana, where we have shared our research findings.

Like Britain, France made extensive use of capital punishment until the late eighteenth century, and although the 1789 Revolution resulted in a huge surge in executions, a new Criminal Code began a process of penal reform in 1791. Agitation for abolition followed. It did not achieve quick success. Public executions continued until 1939, and executions for murder continued to be carried out in France until 1977, although President Valéry Giscard d’Estang had, when standing for office in 1974, declared his ‘profound aversion’ to capital punishment, and opponents included both Catholic and Protestant Churches, the magistracy and the Commission for Revision of the Penal Code.

Campaigning for the presidency in 1981, four years after the last execution, Mitterand declared his support for abolition, despite opinion poll evidence suggesting that 63 per cent of voters supported retention. He appointed Badinter, a distinguished trial lawyer, as justice minister on taking office. Badinter's qualifications for becoming the agent of abolition in France were impressive: he had managed to persuade judges to spare the life of a murderer on the grounds that the death penalty was a cruel and inhuman punishment that risked innocent persons being sentenced to death on no fewer than six separate occasions between 1976 and 1980. It is notable that in France, the execution method still on its statute book was the guillotine.

Germany, the United Kingdom, Canada and other jurisdictions had already abolished capital punishment even though popular opinion was opposed to it. Badinter determined that France was ready to follow suit. In his book, L’Abolition (2000) Badinter notes (at 301) that on the morning of the parliamentary debate on abolition, Le Figaro (17 September 1981) published an opinion poll which showed that 62 per cent of respondents favoured retention, with 33 per cent against. When asked whether they were in favour of capital punishment for particularly atrocious crimes, 73 per cent replied ‘yes’. Very similar levels of support had been found in the UK, Canada and Germany when they were at a similar stage. But as Badinter was aware, once abolition had been enacted, public opposition to the measure had been tepid, and although right-wing politicians sometimes demanded the death penalty’s restoration, in none of these countries had there been anything approaching a serious campaign to bring it back.

The last death sentence for murder in France was handed down in March 1981, two months before Mitterand’s election. (The prisoner, Philippe Maurice, was re-sentenced to life imprisonment, and released on licence in 2000.) Once in office, with commendable resolution, Badinter pushed the law to abolish capital punishment through the French National Assembly and the Senate, gathering some support from the political right as well as more solid backing from the left. Abolition was duly enacted in September 1981.

In many retentionist jurisdictions where the DPRU and DPP work with our partners in Asia, the Caribbean and Africa, governments justify their continued use of the death penalty by referring to the importance of acceding to democratic will to foster a sense of legitimate governance. Following the path suggested by Badinter, our research often seeks to explore what the public really thinks about capital punishment. It thus eases the path towards abolition by exposing an apparent paradox – that in many countries, surveys suggest there are large majorities in favour of retention, yet when abolition does take place, there is rarely a strong public or political pushback. Our experience suggests that one reason is that often, general opinion polls, or surveys done on behalf of governments, are constructed superficially, and so fail to measure the knowledge that opinions are based on, the strength of those opinions or the types of offences or offenders the public believes should be subject to capital punishment.

In recent years, for example, the DPRU and DPP have worked on public opinion research in Kenya and Indonesia that shows that while the majority of the public will say initially that they support capital punishment, the level of support declines dramatically when they learn of the high risk of wrongful convictions, the high probability that the death penalty will usually be awarded to the most vulnerable in society, and about the lack of safeguards and inherent arbitrariness in the criminal justice process and at sentencing. We have also found that most respondents’ interest in capital punishment is low, while even the majority who say they support it would be happy to accept abolition if their government decided to change penal policy. In other words, when we conduct sophisticated empirical research, we find that public opinion is not a genuine barrier to abolition, which can safely be achieved without compromising the legitimacy of governments or the state.

In liberal democracies, where laws are based on the mandate given to elected representatives, it is not incumbent on legislators to follow popular opinion. In an elected parliament, politicians are representatives, not mandated delegates. Other jurisdictions where the death penalty was abolished despite opinion polls suggesting this did not command majority support have also remained steadfast in their determination not to restore it. The parliaments of Canada and the United Kingdom both rejected several attempts to reinstate capital punishment before it was finally abolished for all crimes in all circumstances, despite the fact that in both countries the polls showed substantial majorities at the time in favour of reinstatement. Meanwhile in France, after abolition, Mitterrand was re-elected for a second term, suggesting that capital punishment was by no means the most salient issue amongst voters, and that his political leadership had been accepted.

Robert Badinter, who played such a vital role in ensuring that the death penalty was abolished in France, used to suggest that it usually takes about ten to fifteen years following abolition for the public to stop thinking of the death penalty as useful and to realize that it makes no difference to the level of homicide. Support for this assertion has been found in various jurisdictions across the world.

After Badinter left government, France continued to follow the course he had set. It ratified Protocol 6 of the European Convention on Human Rights in February 1986, ensuring abolition in peacetime, and then, in 2007, acceded to Protocol 13 of the Convention, abolishing the death penalty in all circumstances. It also became a party to the Second Optional Protocol of the ICCPR aimed at abolition. In the same year, on the initiative of President Jacques Chirac, Article 66-1 of the Constitution was amended to state that ‘no one shall be sentenced to the death penalty.’ Since then, France has been a vocal opponent of capital punishment, consistently voting for a worldwide moratorium on executions and encouraging the global movement for abolition. The experience of France, as of other abolitionist nations, suggests that Presidents elsewhere could take the lead in abolishing capital punishment without fear that the public will rise up against them or punish them at the polls.

At the DPRU, we are proud to acknowledge Badinter’s contribution and his legacy, and through our ongoing work with our partners, we intend to honour it.

Carolyn Hoyle is Professor of Criminology in the Centre for Criminology, University of Oxford and Director of the Death Penalty Research Unit (DPRU).

Photo credit: FIDH via Flickr. Licensed under Creative Commons CC-BY-NC-ND 2.0 DEED.

Share: