Opposition to capital punishment among opinion formers in the Eastern Caribbean and Barbados

Posted

Time to read

On 23 November 2021, The Death Penalty Project (The DPP), in collaboration with the Faculty of Law at the University of the West Indies, held a roundtable meeting to explore and discuss the findings of their report on the views on the death penalty of opinion formers across the Eastern Caribbean and Barbados. The event took place online and involved their partner organisations: Greater Caribbean for Life, the St Vincent and the Grenadines Human Rights Association, and the World Coalition Against the Death Penalty. Sadly, the lead author, Professor Roger Hood, was absent. His death, a year before this event, and a year after he had written this, his last publication, left a huge gap.

The DPP had commissioned Roger Hood and Florence Seemungal to conduct research to explicate why the six small, independent island nations in the Eastern Caribbean – Antigua and Barbuda, Dominica, Grenada, St Kitts and Nevis, St Lucia, and St Vincent and the Grenadines – and the neighbouring island of Barbados, retain the death penalty in their criminal statutes, despite not having executed anyone for a very long time.

Though there was an execution in St Kitts and Nevis in 2008, no one has been executed in any other countries in this region for over 20 years, and in most of these countries, death sentences haven’t been imposed and, indeed, most death rows are empty.

Who are ‘opinion formers’?

Hood and Seemungal, with assistance from Amaya Athill, carried out interviews with 100 knowledgeable ‘opinion formers’ to understand their views and attitudes about the death penalty. They were selected from four areas of public life: politics and the senior ranks of the civil service; criminal justice and legal practice; religious leadership; and well-regarded and influential members of civil society.

Criminal justice policies and laws, including those pertaining to the death penalty, are often the result of competing interests, within the context of media pressure and public opinion, rather the product of a well-reasoned and highly strategic processes. It is important, therefore, to understand the opinions of those who can influence both the public and the political elites.

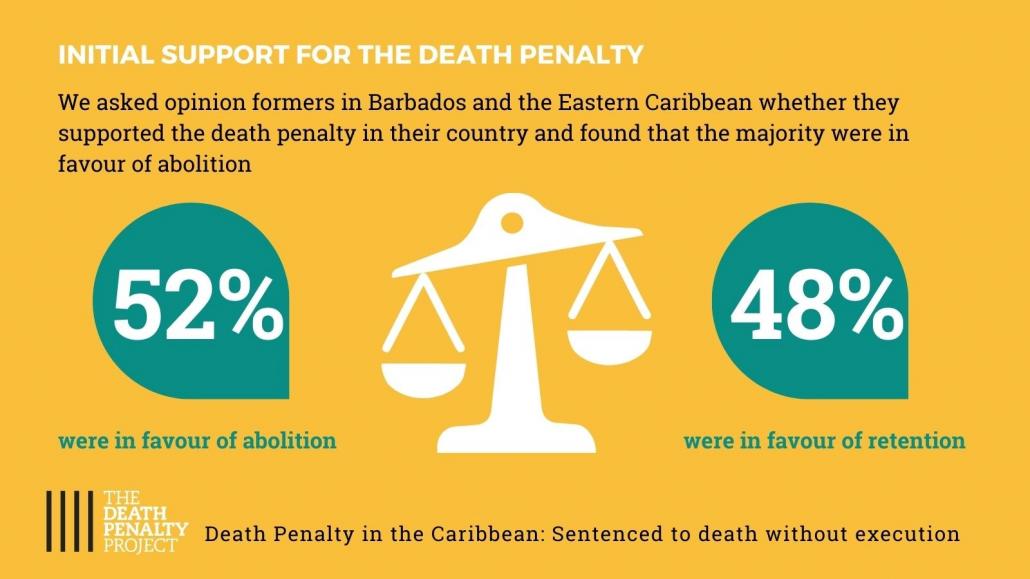

A majority of opinion formers are in favour of abolition

Across these seven small nations, the majority (52) of opinion formers were in favour of abolition, many (30) of them strongly in favour of abolition, and fewer than one in five were strongly in support of capital punishment. Strength of opinion is important: support for the status quo is not uncommon, but here we see very few people espousing views that could be a barrier to reform.

Furthermore, there was less support for the death penalty among those in criminal justice or legal positions than among those in politics, civil society, or the clergy. This suggests that those who know most about the administration of the criminal justice system are least in favour of retaining capital punishment.

Rationales for favouring retention or abolition of the death penalty

The vast majority (84%) of those who favoured retention did so for retributive reasons – the idea that some deserve to be executed. No one supported the death penalty because they believed public opinion is opposed to abolition. Still, when asked why their governments have not yet abolished, the majority of opinion formers said it was because the government believes most of the public are in favour of the death penalty and that abolition would therefore make the government unpopular. This is an interesting finding. It suggests that opinion formers have more nuanced views about the extent to which a largely uninformed public should influence sentencing. The opinion formers themselves clearly don’t believe it should, but suspect that their government is at least partly led in its decision not to abolish capital punishment by concerns that it could harm their government’s popularity.

What is important though is that only a small proportion of those who favoured retention had an appetite for more death sentences or for the death penalty to be available for a greater range of offences.

Two-thirds of those who favoured abolition did so because they believed the death penalty had no extra deterrent effect (beyond that of a life or very long prison sentence); because capital punishment is an abuse of human rights; or because of the possibility of wrongful conviction and execution.

No faith in deterrence

Only 10% of those who favoured retention of the death penalty gave deterrent rationales. Furthermore, in line with all other opinion research commissioned by The DPP, appetite for capital punishment for its alleged deterrent effect is weak when interviewees are questioned about measures to reduce serious crime. When opinion formers in this study were asked about what policies might best control violent crime, the majority showed a preference for better education of young people against the use of violence, with only two of the 100 interviewees choosing ‘more executions’.

We might imagine that elites in countries with high crime rates would choose policies that reflect ‘penal populism’ – the idea that harsh penal policies, rather than social justice measures, are necessary to solve crime. Yet here we have opinion formers demonstrating greater faith in social justice.

What might be the consequences of abolition in the Eastern Caribbean and Barbados?

Opinion formers believed that their governments’ reluctance to follow the international trend towards abolition could be explained by reference to the importance of national sovereignty and cultural exceptionalism. While they felt governments were mindful of the strength of public sentiments and had concerns about maintaining electoral popularity, even those who supported the retention of the death penalty did not think that public opposition to abolition should influence government policy.

More importantly, they did not think that there would be grave consequences if the death penalty were to be abolished; they believed that the vast majority of the public would not oppose abolition of capital punishment if their government were to take the lead. Indeed, the majority (three-quarters) of opinion formers thought that either most of the public would immediately accept abolition or that while there might be some expressions of dissatisfaction leading up to abolition, most of the public would come to accept abolition once a law was passed. Only one in five thought there could be demonstrations of strong public dissatisfaction if the death penalty were to be abolished.

There is clearly not an appetite among opinion leaders in the Eastern Caribbean and Barbados to jump-start the death penalty in this region. Indeed, the findings of this report suggest that opinion points in the other direction. Furthermore, opinion leaders are confident that the public will follow the lead from their governments if they are inclined to abolish, as they have done elsewhere.

The public in this region, as in all countries, are not likely to be well informed about the administration of capital punishment. People tend not to know about the unacceptably high risks of it being arbitrary and unfair, applied to the most disadvantaged and vulnerable defendants. And they will not likely know that capital punishment has not been shown to deter murder in any jurisdiction.

A wider Commonwealth phenomenon?

The question pertinent to the Caribbean region, and in fact the wider Commonwealth, is why do so many of these countries keep the death penalty on the statute books, while they have not carried out an execution for many decades? Of the 54 Commonwealth nations, some 37% are regarded as abolitionist de facto by the United Nations; so, they retain the death penalty but have ceased to carry out executions for more than ten years. The proportion of de facto abolitionist countries in the Commonwealth is much higher than in other regions. These countries (including the 13 nations of the English-speaking Caribbean) grimly hang on to capital punishment, asserting that it is their sovereign right to reject the view that abolition is a universal human rights norm.

The seven Caribbean countries included in the study are illustrative of the wider phenomenon across a third of the countries in the Commonwealth. Executions cease and become a matter of historical record in nearly all abolitionist de facto states, yet the longer the status quo remains, the possibility that states will take the final bold step to abolish the death penalty altogether diminishes over time. Should this matter if executions become obsolete? There are many reasons to suggest that not only should all countries be on an irrevocable path towards abolition, but they also need to take steps to remove capital punishment from the statute books. Doing nothing raises fundamental concerns.

The dormant existence of the death penalty in law can readily be translated into political reality in response to a heightened fear of rising crime or political instability, such that the practice of executing offenders can be revived after decades without use. Furthermore, in many Commonwealth countries, including some in the Caribbean region, countries remain in abolitionist de facto status for decades, yet continue to sentence to death many people over that time. This is a dysfunctional approach to penal policy and represents a failure to shed the vestiges of an inhumane practice.

Critically, while a state remains abolitionist de facto, the idea that it is legitimate for the state to kill its citizens remains embedded in the culture, whereas abolition de jure signals that it is unthinkable for a government to employ the death penalty.

The Caribbean region is stigmatised by holding on to a punishment that most other countries have abandoned with no ill effect. The retention of the death penalty is based on assumptions that leaving the death penalty on the statute books without enforcing it is sufficient. This report challenges these assumptions and provides these governments with a strong and coherent case for abolition, and the confidence that after such, the public will not look back.

Roger Hood and Florence Seemungal's report, Sentenced to Death Without Execution: Why capital punishment has not yet been abolished in the Eastern Caribbean and Barbados, can be read in full on The DPP website here.

Carolyn Hoyle is Professor of Criminology in the Centre for Criminology, University of Oxford and Director of the Death Penalty Research Unit (DPRU). Saul Lehrfreund is Co-Executive Director of The Death Penalty Project.

Share