In 2009, 25-year-old Tuti Tursilawati from West Java, Indonesia, left her four-year-old son to travel to Saudi Arabia to work as a maid in order to support her family. According to her account, her employer, a Saudi man, regularly sexually abused her while she lived and worked in his home. One day in May 2010, when her employer tried to rape her again, Tuti tried to defend herself with a stick and hit him, causing his death. She fled the house and tried to get away to safety. Instead, she was found by a group of nine men who gang raped her. She was arrested by the police one week after her employer died and was sentenced to death for his murder in 2011, despite the circumstances.

Amnesty International has consistently ranked Saudi Arabia among the top five global executing states. In 2019, 184 executions – which are carried out by beheading, often in public – were recorded in the country, with almost half of the individuals executed (84) having been convicted for drug-related offences. The broad range of other offences that can be punishable by death includes murder, rape, terrorism-related offences, robbery, apostasy and witchcraft. Depending on the nature of the charges, the imposition of a death sentence may be mandatory under the country’s strict Sharia legal system. Though it is against international law to sentence minors to death, Saudi Arabia continues to sentence and execute people for crimes committed whilst they were under the age of 18.

These executions are the product of a criminal justice system characterised by secrecy and arbitrariness. The total number of individuals currently held on death row is unknown, and death sentences have frequently been carried out following trials which did not meet international standards, including cases in which defendants were convicted on the basis of ‘confessions’ believed to have been obtained under torture.

Within this system, it is foreign nationals who are disproportionately at risk of death sentencing and execution, particularly poorer migrant workers. At least 90 of the 184 individuals (49%) who were executed in 2019 were foreign nationals, and nationals of at least 29 countries are known to have been executed in the past. Among the countries whose nationals have been most severely affected is Pakistan, with many more Pakistanis reportedly executed in Saudi Arabia in the past than any other foreign nationality. The NGO Justice Project Pakistan (JPP) has documented the execution of Pakistani citizens following trials which were solely in Arabic, with no translation. JPP have detailed further fair trial issues faced by many foreign nationals in the country, such as lack of access to legal representation and pressure to sign ‘confessions’. It has been noted that Saudi officials rarely meet their obligation under the Vienna Convention on Consular Relations to inform consular officials of the detention of foreign nationals. In fact, foreign nationals are often executed without first informing their consulates. NGOs have also stated that they are denied access to prisons to support detainees or offer legal representation.

A construction site in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Photo credit: Pixabay.

The nature of the diya system, in which a murder victim’s family may accept blood money on behalf of the accused in exchange for full or partial clemency, further disadvantages foreign nationals who do not have the social networks or means to meet the family’s demands. The victim’s family can choose what level of blood money they would accept, and this usually amounts to sums well outside the means of a migrant worker. Etty Binti Toyib, an Indonesian woman, was sentenced to death in 2001 at the age of 32 after being accused of poisoning her employer. The family of the deceased demanded $1.3m US dollars. Concerned individuals and organisations managed to raise $1m for Etty over the years, which was accepted by the family, allowing her to be released aged 51, after 19 years in prison. However, many do not benefit from charitable donations.

Certain countries of origin have made attempts to safeguard the rights of their nationals and in 2011 Indonesia signed a moratorium to stop sending domestic workers to the Gulf state after another Indonesian maid was executed. However thousands still travel there each year as they know their families rely on the remittances sent back home.

After eight years in prison, Tuti was beheaded on 29 October 2018. The Indonesian consulate were not informed of her planned execution until after she was executed. Just one week before, Saudi Arabia’s foreign minister Adel al-Jubeir had met with the Indonesian foreign minister Retno Marsudi to discuss migrant workers’ rights in the country, including a mandatory consular notification requirement before any planned executions.

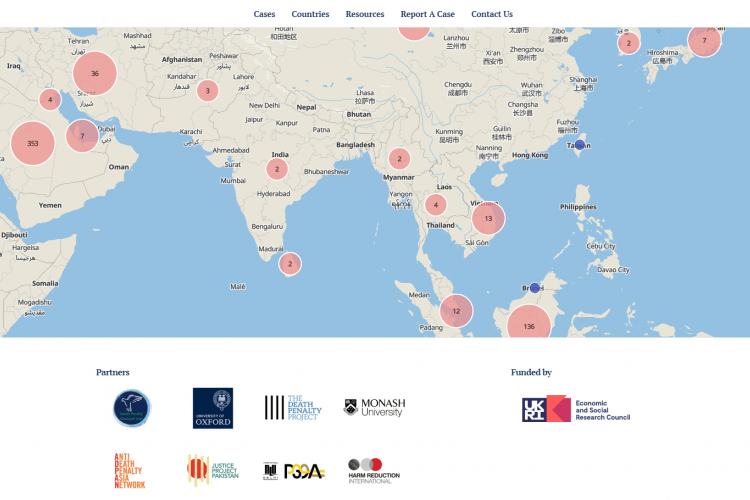

In recognition of the extreme plight of foreign nationals on death row and their particular vulnerabilities, the Death Penalty Research Unit at the University of Oxford have been working with a network of NGOs to map foreign nationals at risk of the death penalty across Asia and the Middle East. As the data is being gathered, HURIDOCS, a human rights software developer, is developing an interactive database, Mapping Death Row, that will record socio-demographic, jurisdictional and offence-related data, as well as producing data visualisations and maps which will illuminate the numbers and trends emerging. Once the project is complete, the database and accompanying resources will be made freely available, upon subscription, to lawyers, activists, academics and relevant civil society organisations to enable them to better assist foreign nationals on death row through activism, advocacy or litigation.

In Saudi Arabia, where we have already gathered data on several hundred foreign national cases, we have discovered that there have been at least 358 foreign nationals on death row since 2016. Of those, around 298 have since been executed, while 52 remain on death row. 18 of the foreign nationals sentenced to death since 2016 were women, one third of whom were Ethiopian and one quarter Indonesian. 63% were sentenced for drug offences, 30% for murder, and the remaining 7% for offences including witchcraft, burglary, rape, adultery and kidnapping. At least 26 nationalities were represented on death row over the past five years: 126 people were from Pakistan (35%), 62 were from Yemen and the remainder from other countries across Asia and Africa. No European or North American nationals have been executed in the last five years or are currently on death row.

While we have gathered a considerable amount of data on Saudi Arabia, we know there are more cases to be found and there is much less data available for other countries in the Middle East. Anyone with access to data on foreign nationals who have been executed or are at risk of capital punishment within the Middle East, or the rest of Asia, who would be interested in collaborating with us on this project, can contact Jocelyn Hutton, the Research Officer on this project. We also seek further funding to ensure that this important work can be developed across retentionist countries on the African continent and in the Caribbean. If you would like to contribute, we would be delighted to hear from you and to have you join us on this exciting new project. It is our hope that this will prove a valuable resource to civil society, providing an important tool to effect change for this vulnerable and disadvantaged population.

Share: