Opinion: The impact of gentrification on ethnic communities

Rachel Bale is a future pupil barrister at 3PB, where she will undertake a Property/ Commercial pupillage. She is also author of Lady of the Land, which discusses elements of property & land law from a female perspective.

Posted:

Time to read:

In March 2021, The Sewell Report found “no evidence of systemic or institutional racism in Britain” and stated that “most of the disparities examined… often do not have their origins in racism.” However, in the same breath, it also found that “ethnic minority Britons are more likely to live in persistent poverty and overcrowded housing”, with 28% of people in black households being on persistent low income, the highest of all groups, compared to 12% of white households. Housing was not discussed in any detail throughout the report, which conveniently avoided the topic of insecure, precarious living situations and the profound effect this has on people of colour.

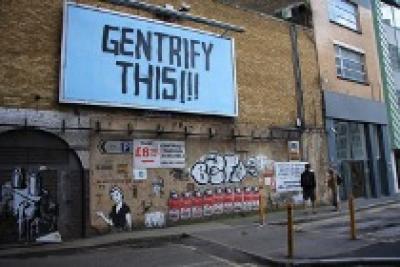

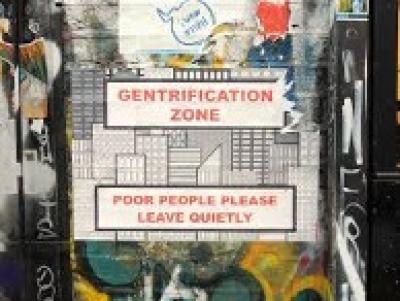

This article analyses the growing trend of gentrification, arguing that its deeply sinister motive, at best, seeks to ‘displace’ and, at worst, to ‘cleanse’ ethnic community areas, having a noticeable effect on black communities. Whilst this article recognises that ‘white’ working class areas have also been affected by the influx of gentrification, this article unapologetically focuses on the distinct effect this process has on ethnic communities, choosing to not only discuss the impact of race on gentrification, but to suggest that this process is inherently racialised.

Methods of gentrification

The term gentrification is used to describe the migration of a higher socioeconomic group into a lower socioeconomic area, therefore exploiting ‘rent gaps’ which cause a disparity between the potential ground rent level (land value) and the present actual ground rent. This is often triggered by a surge of younger, wealthier people becoming fascinated with living in more deprived areas, which raises property prices out of reach for the existing residents. For supporters, gentrification is ‘rejuvenation’ focused on ‘improving’ local areas to be more desirable places in which to reside. However, for many, this process comes at a cost.

Many locals who live in these areas are ‘displaced’ and have little choice but to leave their homes. As reported in 2014, increasingly local authorities pass control of their stock to private housing associations who in turn lease this land for a few centuries to big developers. Here, social housing is replaced with a denser mix of ‘affordable’ housing cross-subsidised by more expensive homes, which make up the majority of properties, with the latter often being sold on a Shared Ownership basis. According to Marcuse & Watt’s work, displacement can take several forms:

- ‘direct’ either via physical coercion through housing demolitions or landlord evictions (local authorities can also use their state power of compulsory purchase);

- ‘economic’ via much higher annual rent, service charges and bill increases, now that payment is made to a private bodies rather than social housing; and/or

- ‘indirect’ or ‘displacement pressure’. This occurs when local residents see their neighbourhood changing dramatically, with local amenities being replaced with more expensive options, causing them to feel excluded.

The most concerning form of gentrification is ‘state-led’, as theorised by Watt in the form of a pair of scissors. Watt describes the state’s two ‘blades’ as, firstly, raising land values and, secondly, implementing long-term running down of council housing both in terms of numbers and quality. This was demonstrated by The Guardian, 2014, where interviewees from Woodberry Down discussed how the local council allowed the estate to become dilapidated, refusing to repair common areas, allowing the play areas for children to be closed, all culminating in a form of ‘constructive eviction’ where it became untenable for residents to live there.

Furthermore, there have been reports of social housing leaseholders being offered attractive rehousing agreements under ‘like-for-like’ terms in the same borough. However, as the plans progressed, the assurance disappeared, replaced with the offer of financial compensation well below current purchase prices, or a property offered under very different terms (e.g. shared ownership).

Racialised rationale behind gentrification

Gentrification has many faces but, as Danewid claims, it is “typically underpinned by a set of racialised assumptions about who belongs in certain spaces and who does not”. The prevailing discourse tends to discuss the impact on non-white communities as a by-product, an unfortunate conclusion to an otherwise worthwhile pursuit.

However, this process of displacement, as Danewid argues, is predicated on racial capitalism, “a racial and imperial political economy that produces some people and places as ‘surplus’”. Capitalism is predicated on production, with those who profit the most (owners) normally having relied upon the labour and exploitation of those below them (workers). Racism is intrinsic to these methods, as it supplies the precarious and exploitable lives that capitalism needs to extract land and labour. Historically, we have seen how the human lives of ethnic communities have been valued only by the labour they can produce through ‘chattel slavery’, with this racialised exploitation continuing today through immigrant labour – often underpaid.

The process of gentrification begins with providing justifications for regeneration programmes that build on stereotypes, associating areas “with crime and deviance, consolidated in long-standing images of ‘sink’ estates” (Cooper, Hubbard, and Lee). These ‘problem’ areas typically all have a large ethnic community presence. Cooper discuss three estates in London located in Haringey, Newham and Southwark noting that almost all tenant interviewees were from minoritised ethnic groups. These interviewees explain how their areas have been continually racialised with stigmas of “poverty”, “roughness”, “riots” and “gang-related” violence being offered as justification for redevelopment. This stereotype is often met with over-policing of these “problem” areas by “cleaning up the streets’ and creating “safe” spaces for capital investment, urban redevelopment projects and middle-class consumer habits.

Racial capitalism is underpinned by colonialism. As El-Enany describes, “Britain’s geography is marked by spaces of colonial control and exclusion in which resources are withheld from people living in conditions of spatial and temporal precarity”, almost always non-white. Rapid gentrification in historically poorer and ethnic areas, where local councils overtly prioritise the interests of newer, predominantly white, wealthy residents, is just a further example of colonial practices determining who has access to which resources in Britain.

Effect on ethnic communities

To be dispossessed of one's home has far-reaching consequences. It has been analysed by Fried as "unhoming" in that "just like a plant; when you tear up its roots, it dies". This metaphor was reused some 40 years later by Fullilove to describe the "root shock" experienced by black communities displaced in the name of modernisation.

Numerous case studies echo this same feeling with the slow, incremental change of amenities, with higher price tags all tailor-made for the new residents. Baginski and Malcom state that "gentification functions aesthetically, commodifying architectural styles and fashion, as well as racial and ethnic identity...modifying physical urban environments to present ongoing political and racial conflicts as matters of taste". Existing residents feel alienated upon seeing the numerous artisanal bakeries and farmers' markets appearing in place of their former culturally influenced supermarkets, cafes and hairdressers. Many do not possess sufficient economic and cultural capital to afford and frequent such establishments. Consequently, they feel detached and unwelcomed.

This alienation has a direct effect of 'cleansing' areas of their ethnic influences, all in the name of 'improvement' and 'bettering'. This was demonstrated in the area of St Pauls, Bristol, which historically was predominantly inhabited by the Caribbean community, especially since 1952. Following changes, locals complained that their cultural community was disappearing, with new owners choosing to renovate eateries and bars into blocks of flats for more profit.

This deliberate restructuring of cities can lead to "antagonistic class relations" as a creeping narrative settles that only those with substantial money and power (e.g. corporations and sometimes wealthy individuals) have a "right to the city" (Watt). Divisive notions of imprecise social categories ('them and us', 'rich and poor') can arise, which threatens existing residents' previous sense of local place and identity.

Whilst Watt, like many other scholars, chose to discuss these tensions from the central focus of ‘class’ only, this fails to recognise the impact that race, as a distinct category has on gentrification projects. The word “urban”, for example, has a dual sentiment. Technically it describes a highly built up area inner-city, however, for many the sentiment is code for ‘black people live here’, a cloaked word implying poverty and a dilapidated area, all from a racialised point of view as argued by Eddo-Lodge. Danewid discusses how scholars continue to treat race as “an individual mentality or as an exception from normality, rather than as a form of structural coercion that is built into capitalist structures and institutions.” To protect ethnic communities from gentrification, race must first be recognised as a socio-political category of distinction on its own.

Conclusion

The Sewell Report fails to analyse the impact of colonial, racialised practices in housing in general, but more specifically through the rapid methods of gentrification. With scholars failing to recognise the direct impact race has on gentrification projects, the impact of racial capitalism on ethnic communities is catastrophically ignored. Gentrification creates the allure of improvement of ‘undesirable areas’, but the reality is a deliberate attempt to cleanse these areas of those who are deemed ‘surplus’, removing their sense of place and locality while simultaneously removing them from their homes.

___

How to cite this blogpost (Harvard style):

Bale, R (2021). Opinion: the impact of gentrification on ethnic communities. Available at: https://www.law.ox.ac.uk/housing-after-grenfell/blog/2021/05/opinion-impact-gentrification-ethnic-communities (Accessed [date])

Keywords:

Share: