Unaffordable bills: Is bankruptcy meant for this?

Dr Joseph Spooner is an Associate Professor in the Law Department at the London School of Economics. He researches issues of law, policy, and politics relating to household debt and financialisation. His recent book, Bankruptcy: the Case for Relief in an Economy of Debt, explores the public policy benefits of household debt relief in our contemporary debt-dependent economy. It considers how bankruptcy law can act as a mechanism of social insurance against the risks inherent in a financialised economic order.

Posted:

Time to read:

Fire Safety Bills and Bankruptcy

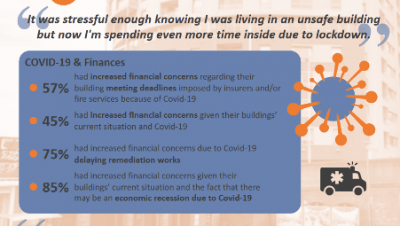

Since the Grenfell Tower fire thousands of residential buildings have been found to be unsafe. Each week new stories emerge of leaseholders being hit with unimaginably high costs, both from the ‘interim’ costs of ‘staying safe’ (insurance, waking watch, fire alarm installations) and the remediation costs of ‘making safe’. On top of this many are also suffering from the financial shock caused by COVID. Unsurprisingly, many leaseholders will simply be unable to pay. The sums are too big. The recent survey conducted by UK Cladding Action Group reveals the devastating emotional toll this is having and contains many references to the prospect and fear of bankruptcy:

‘I struggle each day to keep myself alive due to the financial worries of ending up homeless and bankrupt’.

Bankruptcy can also have wider consequences:

‘I will lose everything including my job and professional standing -which prohibits me from practising if I am declared bankrupt.’

This should not be happening. The government needs to erect fences to prevent those without any responsibility for the building defects from falling off this financial cliff. But in view of the current position and given how little is often known about bankruptcy, we thought it would be useful to provide a series of posts that explain what bankruptcy is, when it might be useful, and what the impacts can be. This first post situates bankruptcy within the wider economic context, and in the second post Joe Spooner sets out how the bankruptcy and personal insolvency system works. In a future post, Joe will look more specifically at loss of home, and the reputational and other impacts of bankruptcy.

The Societal Benefits of Bankruptcy

To understand the purpose of bankruptcy we have to see how it sits within our contemporary economy and how, in this context, the personal insolvency or bankruptcy system acts as a form of social insurance, and a safety net of last resort against the risks of a debt-dependent economy. The modern economy depends on high levels of household debt to fund both wider economic growth and households’ access to the fundamentals of a reasonable standard of living (including housing, transport, education, even healthcare). Increased debt has come to fill gaps between stagnant wages and rising living costs, while increased recourse to private markets, often accessed through borrowing, has compensated for a shrinking Welfare State.

The flip side is that debt dependence can bring major problems, including economic stagnation (as current and future resources/income are used to pay back historic debt), inequality, and financial precarity. The heightened level of risk is particularly evident in the housing market in which households must now incur debts at levels unimaginable a generation ago to meet housing costs. Many leaseholders had already stretched themselves financially in order to finance the purchase of flats, giving little room to weather future financial shocks.

These trends expose our economy and individual households to new dangers and the system of bankruptcy is designed to protect against such risks. By discharging debts, bankruptcy can offer households a means of overcoming financial calamity and beginning anew. This produces wider economic benefits in addressing the social costs of over-indebtedness (including health problems, housing and welfare support costs, lost economic activity and labour productivity), and the discharge of debts means that the credit markets, where the debts originated, must bear the costs of those debts not being paid. Costs that could be devastating for an individual household can be spread across a credit market in a predictable manner which reduces overall costs. Where the households carrying large debt burdens lack the resources to spend further and contribute to the economy a point arrives where more is lost than gained by requiring households to repay unbearable debts. In these ways, benefits of bankruptcy’s debt relief accrue not just to those households benefitting from its use, but can work to the advantage of the economy and society as a whole.

This theoretical justification for bankruptcy is based therefore around the understandings about the role of debt within contemporary economy. Research shows that household over-indebtedness arises largely in two categories of situation: where a household has lived long-term on a low income before reaching a tipping point at which ends do not meet; or where a household has been managing to repay borrowings largely without problems until the arrival of an “income shock” such as unemployment, ill health, or family breakdown. Neither of these situations is applicable to the cladding context in which households in an otherwise sound financial position have been pushed suddenly into difficulty by wholly unforeseeable, involuntary, and significant new costs, often demands for five figure sums.

The Two Faces of Bankruptcy: Stigma or a New Beginning?

Bankruptcy is often deeply unwelcome. Despite its widespread use and the efforts of policymakers in recent decades to reduce the stigma it carries, negative connotations persist. For some, bankruptcy might still be perceived as official confirmation of financial failure. Even in the United States, where average families have long used bankruptcy on a much greater scale than in the UK, people tend to fight through all manner of deprivation and financial struggle before taking the step of filing for bankruptcy.

Nonetheless there is another side to bankruptcy. A classic description of the positive potential of bankruptcy explains that the

purpose of [bankruptcy] has been again and again emphasized by the courts as being of public, as well as private, interest, in that it gives to the honest but unfortunate debtor who surrenders for distribution the property… a new opportunity in life and a clear field for future effort, unhampered by the pressure and discouragement of pre-existing debt.

The fundamental feature of bankruptcy is that it allows an individual (who complies with relevant conditions) to emerge from the procedure free from debt – on completing the bankruptcy process, an individual should obtain a “fresh start”. Bankruptcy is a unique societal institution in its cancellation of debt routinely and as of right. Under English law, an individual who enters bankruptcy can emerge debt-free within one year. Tens of thousands of individuals are relieved from the burden of unpayable debt annually through the personal insolvency system, and the system could potentially assist many more. Rather than being understood as a debtor’s prison, bankruptcy can be seen as a path to future freedom and a means of escaping financial difficulty. Instead of the definitive end of a story of financial failure, bankruptcy has the potential to operate as the beginning of a brighter debt-free phase of life. This not only benefits a person struggling with debt, but also offers societal benefits by reducing the social costs associated with over-indebtedness, and by restoring indebted individuals to a position in which they can contribute more wholly to our economy and society. In this sense bankruptcy has sometimes been compared to a financial hospital - no one wishes to end up in hospital, but when sickness strikes we are thankful for its existence.

Limitations of Bankruptcy

The ability of bankruptcy to offer debt relief and a “fresh start” will depend on the shape of a bankruptcy law, especially the criteria for accessing relief and the conditions attached. The extent to which the lived reality of bankruptcy actually corresponds to its progressive potential is a constant and complex question. While this issue remains under-researched, studies in various jurisdictions have shown that bankruptcy can offer differing levels of assistance to different groups. For some, bankruptcy provides vital relief from crushing debt, allowing people to free up limited resources and make ends meet. Debtors holding greater resources might be able to use bankruptcy as a chance to rebuild towards future prosperity.

For many, however, bankruptcy is a poor substitute for the income support and public services that could be provided through robust welfare state protections. The debt relief offered by bankruptcy can also come at a high cost, typically requiring the surrender of non-essential assets for the purpose of repaying creditors, and the loss of significant wealth (including a home) may be a severe price to pay. Other costs of bankruptcy might involve disadvantage in employment and credit markets for those holding the status of a “bankrupt”.

Where financial difficulties are caused by a single issue other more targeted solutions (compensation, redress, public insurance schemes, social transfers, etc.) might be preferable. Of course, this is the case in the context of fire safety remediation: the solution should lie elsewhere and, as the government has constantly repeated, it should not be leaseholders who have to pay. For now, however, the fear of bankruptcy is real for many leaseholders facing impossible bills. Future posts will therefore explain more about the process of bankruptcy.

__________

How to cite this blog post (Harvard style)

Spooner, J. & Bright, S. (2020). Unaffordable bills: Is bankruptcy meant for this?. Available at: https://www.law.ox.ac.uk/housing-after-grenfell/blog/2020/07/unaffordable-bills (Accessed [date])

Share: