On 17 June 2017, three days after the Grenfell fire, an Expert Group met at the DCLG. They identified three types of ACM cladding, commonly referred to as PE, FR and A2, which have a polyethylene core, a fire retardant core, and a Euro Class A2 ‘limited combustibility’ core respectively. They took the view that the Approved Document guidance allowed only one type to be used on buildings over 18 metres high, and a DCLG letter sent the following day claimed likewise that the guidance allowed only the A2 grade on such buildings.

A further DCLG letter of 22 June 2017 contained in a footnote a more exact statement and defence of the government position, based on the terms of AD B2 2013 12.7, which contained a limited combustibility requirement for ‘Insulation Materials/Products’, and began:

‘Insulation Materials/Products

12.7 In a building with a storey 18m or more above ground level any insulation product, filler material (not including gaskets, sealants and similar) etc. used in the external wall construction should be of limited combustibility (see Appendix A).’

The letter referred to the core as ‘the insulation within Aluminium Composite Material’, a descriptor which was accompanied by the following footnote:

‘For the avoidance of doubt; the core (filler) within an Aluminium Composite Material (ACM) is an “insulation material/product”, “insulation product”, and/or “filler material” as referred to in Paragraph 12.7 (“Insulation Materials/Products”) in Section 12 “Construction of external walls” of Approved Document B (Fire safety) Volume 2 Buildings other than dwelling houses. (The important point to note is that Paragraph 12.7 does not just apply to thermal insulation within the wall construction, but applies to any element of the cladding system, including, therefore, the core of the ACM).’

In principle, such an interpretation would still allow the use of FR or PE ACM through a large-scale BS 8414/BR 135 test and classification. But since, as of 30 June 2017, the government had no evidence (Annex A.11) of classified systems of this kind, the alternative route to compliance through the required ‘full scale test data’ (as opposed to so-called ‘desktop studies’) had probably not been employed prior to Grenfell. If the interpretation were correct, PE and FR ACM would therefore have been effectively prohibited under the guidance, making the Grenfell panels non-compliant.

The ‘and/or’ in the footnote cast doubt on whether the core was insulation at all, since it might apparently be a ‘filler material’ and not insulation. Or conversely, it might be insulation but not filler material. If there was uncertainty with regard to each of these possible categorisations of the material, how could the DCLG be sure that at least one of them applied? And in any case, how could it be that the department was unsure about the interpretation of guidance which it itself had published?

In reality, the ACM core is certainly not insulation, since there is a ventilated cavity between rainscreen panels and the external wall. Barbara Lane, in her Grenfell Inquiry Expert Report at F6.5.11 quotes British Standard 8298-4 to the effect that ‘the rain screen layer should be disregarded when calculating the overall heat loss through the wall’, and she concludes (F6.5.13) that an ACM rain screen ‘is not an insulation material or product’.

But if ACM is not insulation, then why should it be covered by a paragraph headed ‘Insulation Materials/Products’? James Bessey, in his Housing After Grenfell blogpost, argues that as a ‘general point of law, headings are not taken into account’ in interpretation. But Ian McLeod, in ‘Principles of Legislative and Regulatory Drafting’ (Hart: 2009, p. 24) finds a ‘judicial consensus’ that headings in legislative Acts are relevant to interpretation, though admittedly carrying less weight than the words of the Act. McLeod adds that they can be a useful aid in ‘identifying… the purpose of the provision’.

Moreover, Approved Documents are issued as ‘practical guidance’ (Building Act 1984, 6(1)) for architects, engineers, contractors, building control officers, and others engaged in building work, who could hardly be expected to be cognisant of principles of legal interpretation in the first place. Would it not have been reasonable for them to assume that a paragraph headed ‘Insulation Materials/Products’ applied to insulation only?

In this blogpost, I examine only the first of the two further grounds presented by the DCLG for their claim that 12.7 applied to the core of ACM panels, and consider whether it may be strong enough to overcome the difficulty presented by the heading. Their contention is that the core may perhaps be ‘filler material’, and presumably in support of this proposition, the department offers ‘filler’ in parenthesis as a synonym for ‘core’.

But it would appear that they were creating a new meaning, not relying on an established one. My conclusion from a search (see paras C.2.1-4, C.5.1-2) of journals and trade periodicals, product certificates, manufacturers’ literature, patents, and the textbook Cladding in Buildings (Brookes & Meijs, 2008), was that the central layer of ACM was never called ‘filler’ prior to the Grenfell fire, but always the ‘core’. Moreover, the minutes of the Expert Group meeting of 17 June 2017 describe Grenfell Tower’s ACM cladding as ‘PE cored’, and make no reference to ‘filler’. In the DCLG’s 18 June 2017 letter, three references were made to the ACM ‘core’ and none to ‘filler’.

Once introduced in the footnote of 22 June, the new term for the core spread with remarkable rapidity. The DCLG’s Explanatory Note of 30 June uses ‘filler’ several times, usually alongside ‘core’, as in ‘core or filler’, ‘the filler – the core’, and ‘the filler material in the core’, but twice on its own, as in ‘samples of ACM filler’. By 20 July 2017, in an ‘Explanatory note on large scale cladding systems testing’, the DCLG were using the term ‘filler’ almost exclusively, the word occurring sixteen times in the document, ‘core’ just once.

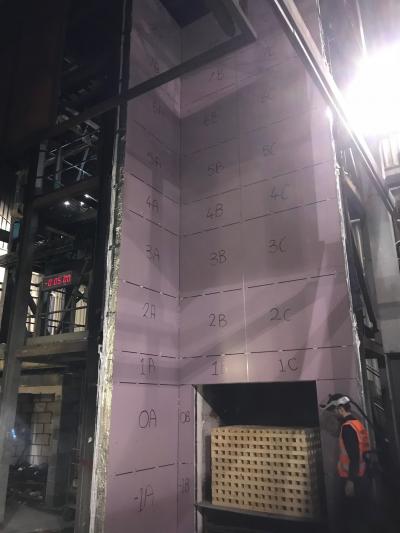

The BS8414 test in action: cladding ready to be tested for fire spread

James Bessey/Blake Morgan LLP

A government press release of 2 August 2017 concerned a large-scale test of a cladding system incorporating ACM panels with what it called a PE ‘filler’. In their reports, the BBC, ITV, and the Guardian all used the same terminology. Thus can new word meanings pass into common usage. But what matters for those seeking truth and justice for Grenfell is what ‘filler material’ meant at the time of the refurbishment. Architects, contractors and building control officers could hardly be expected to have comprehended a meaning of the term that still lay in the future.

It is not as if they would have been searching for a meaning of a term they did not comprehend. Dr Lane demonstrated (F6.5.23,24,45) from an examination of a British Standard vocabulary for Construction Parts that ‘joint fillers’, to fill or partly fill a joint gap, and ‘surface fillers’, to fill voids and undulations in a substrate, are terms in use in the construction industry. I searched for ‘filler’ in a distributor’s web-site catalogue and found a variety of products for filling holes, gaps and cracks. Chris Cook reported for BBC’s Newsnight in August 2017 that, in the context of insulation and cladding, builders used the term ‘filler’ for ‘the foam used to pack voids’.

What is more, the present and former Directors of the Centre for Window and Cladding Technology informed Clive Betts MP, Chair of the HCLG Committee, by letter in May 2018 that Brian Martin, since 2008 the DCLG official with responsibility for Approved Document B, had told them that the term ‘filler material’

‘had been introduced into ADB2 as a "catch-all" intending to stop the overuse of can-applied foam and similar materials to fill gaps within the façade.’

Such gaps occur around windows, around penetrations, and between rigid insulation boards. To avoid heat loss, the filler material must be a good insulator. Polyurethane foam has been commonly used, and mineral wool is the leading limited combustibility alternative. It seems reasonable to describe these as insulation materials.

It is undisputed that previously, from 1992 to 2007, the limited combustibility requirement had been restricted to insulation only. From 2000 to 2007, it applied to ‘insulation material used in ventilated cavities’.

Bessey argues that

‘the whole point of amendments made in 2006 to the earlier Building Regulations 2000 was specifically to identify filler material in addition to insulation materials (and both terms are used in 12.7).’

But it was to insulation product that filler material was added in the new edition, so that there is no necessity to see the added term as something other than insulation. If ‘filler material’ is PU foam, loose mineral wool and similar, these could well have been termed ‘materials’, with rigid rainscreen insulation boards considered to be products, so that paragraph 12.7 could reasonably have been headed ‘Insulation Materials/Products’. There is no need to imagine a novel meaning for ‘filler’, and no basis here upon which to construct a limited combustibility requirement for ACM cladding.

__________

How to cite this blog post (Harvard style)

Chapman, A. (2019). A battle over words: is there ‘filler’ in ACM cladding?. Available at: https://www.law.ox.ac.uk/housing-after-grenfell/blog/2019/03/battle-over-words-there-filler-acm-cladding (Accessed [date]).

Share: