Grenfell, the right to life, and the investigative duty

In this blogpost, Faculty member Dr Douglas S K Maxwell reflects on how Article 2 of the ECHR – concerning the right to life – applies to the British Government's handling of the Grenfell tower disaster and inquiry.

Posted:

Time to read:

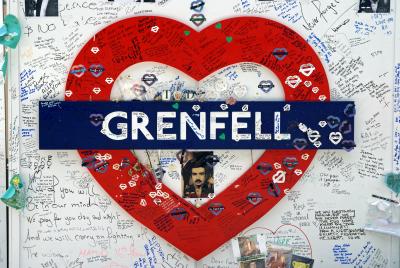

Public mural tribute for the victims of the Grenfell Tower fire disaster

Art. 2 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) states that “Everyone’s right to life shall be protected by law.” The right to life occupies a special position in the hierarchy of values as, without its preservation, all other rights are negated. Art. 2 requires the State not only to refrain from the “intentional” taking of life, but also to take appropriate steps to safeguard the lives of those within its jurisdiction. Article 2 imposes three distinct duties on States:

- A negative duty, primarily not to take life (subject to the specified exceptions);

- the first positive duty, which requires States to take all reasonable steps to protect an individual’s right to life (“the protective duty”); and

- the second positive duty, which commands States to initiate an effective independent public investigation into any death (“the investigative duty”).

The Grenfell Tower fire, which resulted in the loss of 72 lives in North Kensington, engages Art. 2 in several important ways. As the Equality and Human Rights Commission submitted in August 2018, “many of the very systemic failings that led to the Grenfell Tower fire still exist now, giving rise, in our view, to an ongoing violation of Art. 2 ECHR/HRA by the State.” One of the most pressing requirements in relation to the Grenfell Tower tragedy is the second positive duty under Art. 2 to hold an effective investigation. Where lives have been lost in circumstances potentially engaging the responsibility of the State, Art. 2 entails a duty for that State to ensure, by all means at its disposal, an adequate response (judicial or otherwise). This duty is imposed so that the legislative and administrative framework set up to protect the right to life is properly implemented, and any breaches of that right are repressed and punished. As the ECtHR observed in Öneryildiz v Turkey (2005) 41 EHRR 22 at [94]:

[T]he competent authority must act with exemplary diligence and promptness and must of their own motion initiate investigations capable of, firstly, ascertaining the circumstances in which the incident took place and any shortcomings in the operation of the regulatory system and, secondly, identifying the State officials or authorities involved in whatever capacity in the chain of events in issue.

In response to the Grenfell Tower tragedy, the government ordered a full public inquiry and a criminal investigation on 15 July 2017. The investigative duty under Art. 2 requires that the Grenfell Tower Inquiry is: initiated by the State itself; promptly carried out with reasonable expedition; effective; carried out by a person who is independent of those implicated in the events being investigated; and subject to a sufficient level of public scrutiny which includes the involvement of the next of kin of the deceased. It is important to turn to the central requirements of the investigative duty, as set out below.

1. Initiation and Promptness by the State

To be compatible with the investigative duty under Art. 2, States must act promptly. The Grenfell Tower Inquiry was announced by the Prime Minister on 15 June 2017, the day after the Grenfell Tower fire, and the inquiry was formally set up under the Inquiries Act 2005 on 15 August 2017. While the government was swift in setting up the inquiry, we still do not have an end date for the final report. It is expected to continue at least into next year, and perhaps beyond. The government must remember that promptness is important to maintain public confidence; and the longer the inquiry and its protracted proceedings become, the more anguish there is for victims and families. As the ECtHR observed in McCaughey v United Kingdom (2014) 58 EHRR 13 at [145], the State must take “all necessary and appropriate measures to ensure […] that the procedural requirements of [A]rt. 2 are complied with expeditiously.”

2. Effectiveness and Independence

The next principal hallmark of an Art. 2 compliant inquiry is that it is “effective”. The Grand Chamber's decision in Ramsahai v The Netherlands (2008) 46 EHRR 43 (where Dutch police had fatally shot an individual suspected of stealing a scooter) gives considerable guidance. To the Grand Chamber, effectiveness requires adequacy; this is not an obligation of results, but one of means. The authorities must have taken the reasonable steps available to them to secure the evidence concerning the incident. Any deficiency in the investigation which undermines its ability to identify the perpetrator or perpetrators will risk falling foul of this standard. Further, effectiveness requires the person responsible for carrying out the inquiry to be independent from those implicated in the events. As was noted in Al-Skeini v United Kingdom (2011) 53 EHRR 18 at [167], “[t]his means not only a lack of hierarchical or institutional connection but also a practical independence.”

The retired judge, Sir Martin Moore-Bick, chairs the Grenfell Inquiry. This caused alarm as Sir Martin’s past decisions were cited to suggest that his appointment would allow local authorities to “engage in social cleansing of the poor.” The MP David Lammy went as far as to suggest that Sir Martin should not have been hired to lead the inquiry as he is a “white, upper-middle class man” who has “never, ever visited a tower block housing estate and certainly hasn’t slept the night on the 20th floor.” It is not possible to judge the suitability of Sir Martin as chair of the inquiry within the confines of this blogpost. However, it is important to highlight these concerns and the continuing feeling of alienation by the former residents of Grenfell Tower and their families, with their continuing narrative of “us” and “them.” Confidence is key to any public inquiry and, until the Grenfell Inquiry has instilled a feeling of trust and inclusivity, its compatibility with the effectiveness requirement under the Art. 2 investigative duty will remain open to challenge.

3. Public Scrutiny

A high level of public scrutiny is essential to maintain public confidence in the authority’s adherence to the rule of law and to prevent any appearance of collusion in, or tolerance of, unlawful acts. As the ECtHR held in McKerr v United Kingdom (2002) 34 EHRR 20 at [155]:

[T]here must be a sufficient element of public scrutiny of the investigation or its results to secure accountability in practice as well as in theory. The degree of public scrutiny required may well vary from case to case. In all cases, however, the next of kin or the victim must be involved in the procedure to the extent necessary to safeguard his or her legitimate interest.

McKerr concerned the death of Gervaise McKerr, who was killed in Northern Ireland in 1992 after over 109 rounds were fired into a car by police officers, killing all 3 inside, none of whom were armed. In the ensuing inquiry, the ECtHR gave weight to the fact that the inquiry’s reports and their findings were not published in full or in extract. As a result, the ECtHR held that the investigation lacked public scrutiny. The court noted that “[t]his lack of transparency may be considered as having added to, rather than dispelled, the concerns which existed.” Further, in McKerr, no reasons were given to explain the decision that prosecutions were not considered in the public interest, and no possibility existed of challenging the failure to give such reasons.

There have already been criticisms of the Grenfell Tower Inquiry in relation to the redaction of tributes to the victims and the move to Holborn, which was perceived as favouring the needs of lawyers over the survivors and families of the victims. However, it is important to remember that the Grenfell Tower Inquiry plans to publish the entirety of the proceedings, and there is currently a live online stream which is also available on YouTube. The important point for the inquiry is that it continues to publish, in full, all of its proceedings to allow for comprehensive public scrutiny. Further, the families of the victims and residents of Grenfell must be at the centre of any investigation.

Banners from the "Justice for Grenfell" march in London's parliament square.

Image located here and shared under a Public Domain licence.

Conclusion

To discharge the State’s duty to investigate under Art. 2, the ongoing Grenfell Tower Inquiry must satisfy the requirements of promptness, effectiveness, and public scrutiny. Further, and most importantly of all, in order to be compatible with the investigative duty under Art. 2, the Grenfell Tower Inquiry must guarantee that the truth is uncovered. The victims, families, and public have a right to a comprehensive and accurate picture of the events that led to the tragic loss of 72 lives on 14th June 2017.

__________

How to cite this blog post (Harvard style)

Maxwell, D. S. K. (2018). Grenfell, the right to life, and the investigative duty. Available at: https://www.law.ox.ac.uk/housing-after-grenfell/blog/2018/11/grenfell-right-life-and-investigative-duty (Accessed [date]).

Keywords:

Share: