Why are tower block refurbishment projects implemented and whom do they benefit?

Posted:

Time to read:

Thousands of tower blocks were built across England from the 1960s onwards. As a result of age and wear, many local authorities have faced the question of whether to demolish or refurbish their stock of high-rise buildings. Oxford City Council decided to refurbish the five tower blocks in Oxford. The £20 million refurbishment of Evenlode, Windrush, Hockmore, Foresters, and Plowman Towers commenced in 2016 and it is now drawing to a close.

The refurbishment of the Oxford tower blocks has been far from simple. Mid-way though the project, a legal issue arose over who is liable for the costs of the refurbishment. While the majority of the tower block flats are still owned by Oxford City Council and occupied by council tenants, approximately 54 flats (around 15 percent) have been bought under the Right to Buy scheme – the purchasers becoming leaseholders with long leases. Under the terms of the leases, the private owners are required to cover the cost of repairs and maintenance work. However, because these leases do not include improvement clauses, the cost of any refurbishment work that is classed as an improvement cannot be recovered by Oxford City Council. Accordingly, the legal issue in the Oxford tower blocks case centred on whether the refurbishment counted as ‘improvement’ or ‘repair and maintenance’.

Work on the Evenlode in its early (left) and later (right) stages

Images taken by and under the sole copyright protection of author Roxana Willis.

Notably, this legal issue links to the question of why the refurbishment project was conducted: was the Oxford tower block refurbishment designed to improve the building, internal living conditions, and surrounding areas; or was the project pursued with the more modest aim of repairing and maintaining what was already there? The significance of this question goes beyond the legal issue addressed in the Oxford project, and morphs into one that sits much deeper in the public consciousness following the Grenfell tragedy: why are tower block refurbishment projects being implemented and whom do they benefit?

In a forthcoming paper titled ‘Narratives of Tower Blocks Refurbishment’, Susan Bright and I explore apparent reasons for tower block refurbishment by drawing on learnings from the Oxford case study. We collected a range of data with support from our colleagues David Weatherall and Phillip Morrison. The dataset included 23 interviews with various stakeholders involved in the Oxford tower blocks refurbishment; 7 follow up interviews; collection and analysis of legal documents, council publications, and media reports; on-site observational research of the tower blocks and during legal proceedings; and an online survey of the experiences of social housing providers.

Answering the question, ‘Why were the Oxford tower blocks refurbished and whom do they benefit?’ very much depends on to whom and when the question is asked. For example, Oxford City Council’s reasons for the project notably changed in response to wider events.

In the early days, Oxford City Council publicised the project as one that primarily aimed to improve the blocks and surrounding area. Under this earlier promising narrative, the Oxford tower blocks refurbishment can be seen as a part of larger plans to regenerate disadvantaged parts of Oxford, with a view to aesthetically enhancing areas, as well as striving to reach environmental goals of energy efficiency. However, when the legal issue about costs surfaced, Oxford City Council’s publicised reasons for the project notably changed; instead of using the word ‘improve’ to describe the project, Oxford City Council started to underplay the ambitious nature of the works and emphasised the project’s targets to repair and maintain the buildings. The focus of Oxford City Council’s narrative again shifted following the fire of Grenfell tower; the fire safety aspects of the project then became central. Indeed, Oxford City Council commendably went over and above the government safety regulations, and included sprinkler systems in all of the buildings, as well as updating the fire alarms, and including new fire doors.

The First Tier Property Tribunal heard evidence from both Oxford City Council, who claimed that the work had been necessary maintenance and repair, and the leaseholders, who argued most of the work was improvement. The Tribunal decision was more favourable to leaseholders, ruling that most of the work undertaken on the Oxford tower blocks constituted improvement: the new windows, the winter gardens, replacement roofing, and insulation and cladding were all considered to be inessential works which count as ‘improvements’, whereas the maintenance of balcony roofs and floors, the concrete and wall ties, and work to the lifts were considered to involve ‘repair and maintenance’ and thus were recoverable through the service charge provisions in the leases. Consequently, the original bills that Oxford City Council delivered to leaseholders in the region of £40,000 to £60,000 have been dramatically reduced to £2,500 to £4,000.

If the Oxford tower block refurbishment project was primarily one of improvement, then whom did it benefit?

Residents living inside the flats will benefit from improved living conditions – the cladding and new heating systems should increase energy efficiency and reduce bills, for example, and the inclusion of a sprinkler system will improve residents’ safety. However, much of the aesthetically improved aspects of the work is to the outside of the building – the tower blocks look updated, especially from a distance.

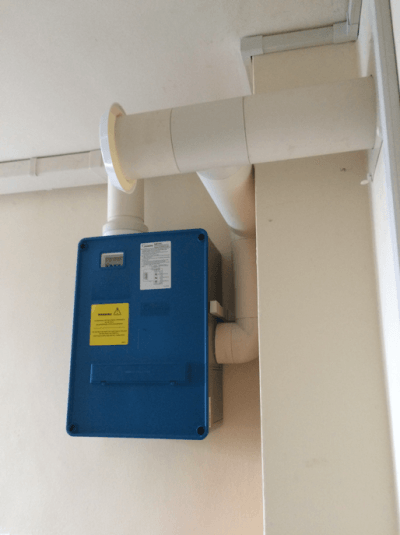

The newly installed ventilation boxes

Image taken by and under the sole copyright protection of Roxana Willis.

Yet much of the internal work was described by the leaseholders we interviewed as ‘industrial’, ‘hideous’, and ‘ugly’. One buy-to-let landlord expressed relief at not having to live with the changes themselves. And one leaseholder, who decided to sell and move on because of the stress of the bills and quality of the works, described the ventilation system installed into each flat as ‘this big massive hideous box that is just horrendous and takes up the size of a boiler cupboard’. While ventilation is necessary to prevent mould inside the building, the systems installed in each flat are reportedly so loud that some residents keep them switched off.

Moreover, there appear to be essential aspects of internal work which have not been addressed at all. A recurring issue experienced by residents we interviewed relates to blockages and flooding inside the flats. Some council tenants’ kitchens flood when their neighbours use their washing machines; other residents have visibly leaking pipes running alongside their bed; the pipes in the flats are said to become blocked often; and in some of the council-owned flats showers have not been installed, so residents must rely on baths instead.

While the Oxford tower blocks refurbishment project has been an ambitious project which will hopefully improve the lives of residents for many years to come, more attention and care for those living inside the tower blocks is warranted. The refurbishment does benefit those living inside the blocks, but not as much as it both could and should.

__________

How to cite this blog post (Harvard style)

Willis, R. (2018). Why are tower block refurbishment projects implemented and whom do they benefit?. Available at: https://www.law.ox.ac.uk/housing-after-grenfell/blog/2018/06/whom-does-refurb-benefit (Accessed [date]).

Keywords:

Share: