Rallying lawmakers in the American South: An investigation of Virginia’s path to abolition

Posted:

Time to read:

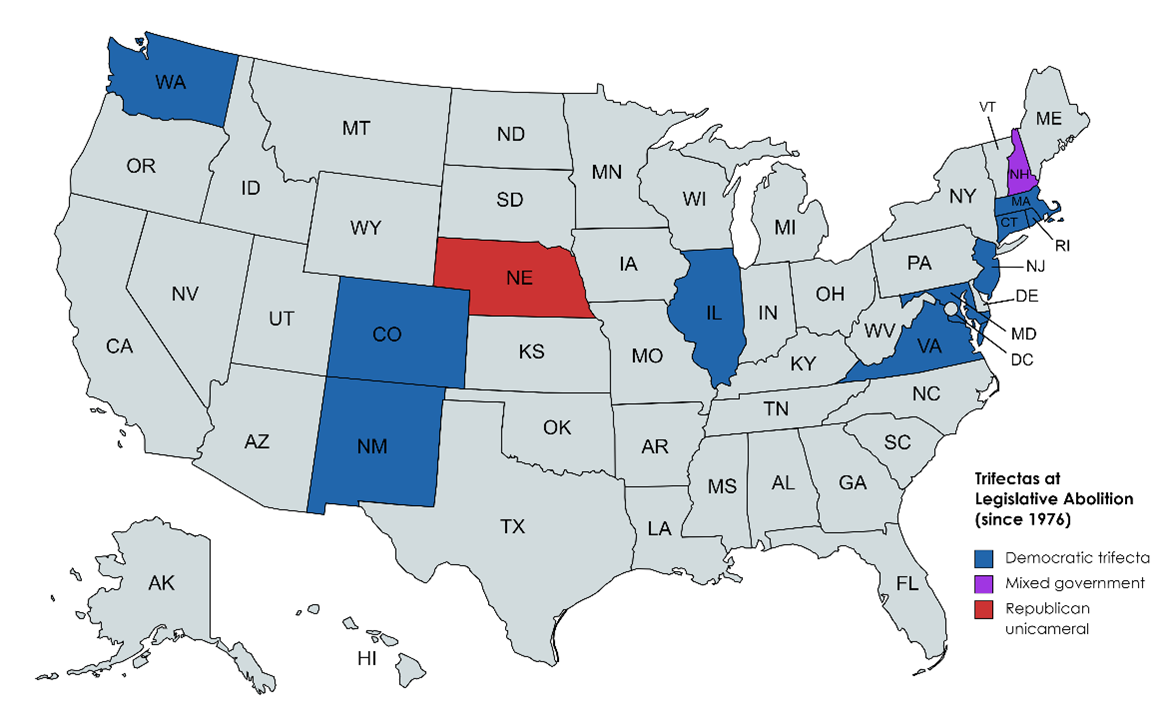

Since 1976, with few exceptions (see Figure 1), the legislative abolition of the death penalty at the state level in the United States has proven contingent upon a few specific factors: (1) the existence of a Democratic state government ‘trifecta,’ where the Democratic Party controls the governorship and majorities in both chambers of the state legislature; (2) proximal triggering events, which prompt the statewide momentum necessary to achieve legislative abolition; and (3) legislators and organizations willing to ‘champion’ abolition.[1] Informed by a series of interviews conducted by the author with legislative and legal elites, as well as research into the legislative record (analysis of floor speeches, amendment sponsorship, and committee votes), this post explores Virginia’s abolition of the death penalty, which occurred in 2021 and follows the pattern of nearly every abolitionist state before it.

In 2020, voters ushered in the first Democratic trifecta in Virginia since 1993, largely a consequence of a statewide shift in demographics over the last three decades. On the matter of proximal triggering events, calls for racial justice boiled over following Virginia Governor Ralph Northam’s blackface scandal, the murder of George Floyd in Minnesota, and heated debates about the removal of Confederate monuments, many of which were designed to glorify the South and its legacy of slavery following the Civil War. The Field Director for Virginians for the Alternatives to the Death Penalty (VADP), Dale Brumfield, described these events as the ‘tipping point’ that pushed legislators to act against the death penalty in Virginia:

Every state that abolishes the death penalty has a series of events leading up to abolition, but there’s always a ‘tipping point.’ And Virginia had a tipping point … we have been trying for 50 years to abolish, okay, with no success at all. … But the tipping point in the case of Virginia was the race argument. … Three things came together … [and] when that happened, all of a sudden there was a focus on racial history in Virginia.[2]

This ‘tipping point’ that Brumfield describes prompted Virginians’ cultural, social, and legal rejection of the South’s larger history of racial discrimination, and presented an opportunity for newly elected Democratic officials to deliver on their campaign promises to address racial discrimination and inequality. Governor Northam and other elected Democratic legislators ushered in a wave of criminal justice reforms, including tighter gun laws, the legalization of marijuana, and most notably, the abolition of the death penalty, but were aided in large part by organizations like the VADP, which ‘championed’ the grassroots effort to abolish capital punishment in Virginia. Importantly, the VADP seized the change in the political landscape by forging ties with community-based organizations such as the Virginia Interfaith Center for Public Policy (VICPP) to affect the decision-making process of state legislators.

The VICPP proved especially adept at mobilizing large swathes of Black clergy members around the state toward abolition. It held press conferences and faith vigils at (or close to) lynching sites throughout Virginia, which led many constituents to voice their concerns about the death penalty to their elected representatives. Brumfield reflected on the impact of a particular constituent:

This one woman, Cynthia Cunningham, God bless her. She called [Dick Saslaw, the Democratic Senate Majority Leader] every day, and just beat him to death with [what she had learned about capital punishment] and you know what? He voted to abolish. [VADP] had his vote.[3]

The VICPP also curated a letter with 400 signatures from faith leaders throughout the Commonwealth, which members presented to the Virginia General Assembly. This effectively framed abolition as a racial justice issue for lawmakers, who then offered varying testimonies about the death penalty and its ties to racial injustice to garner legislative support for abolition.

In particular, Delegate Mike Mullin, a Democrat who sponsored the repeal bill in the House of Delegates, highlighted the racial dimensions of Virginia’s propensity to execute: white defendants found guilty of murdering a Black victim were only ever executed four times throughout Virginia’s history, a fact that legislators drew upon consistently in their arguments leading up to the final floor vote. Additionally, citing evidence from the Death Penalty Information Center, Senator Mamie Locke illustrated how the lynching of Black victims between 1883 and 1940 maps onto the locations of contemporary executions of Black defendants.

However, the VICPP was not the only partnership that VADP sought out, and racial justice was not the only lens through which it – and legislators – sought to frame the abolition of capital punishment in Virginia. VADP specifically developed a five-year plan for abolition, beginning in 2015, that included diversifying its Board of Directors and courting Republican constituents and lawmakers, especially those who might have otherwise opposed the abolition effort. Michael Stone, Executive Director of VADP, detailed this strategy:

When I came in, VADP was an organization of liberal Protestants, progressive Catholics, and civil rights-oriented attorneys. And that was the organization. And if we were going to win in a Southern state that at the time was heavily Republican, we had to change that culture, we had to diversify the board with people who were conservatives. And so, my focus was almost exclusively on conservative outreach, when I wasn’t fundraising, paying the bills, convening of the board, recruiting new board members, and really working hard to diversify the board politically, because the board reflected that very progressive membership. And so that was a big task for the first couple of years.[4]

In addition to diversifying its Board of Directors, a major facet of VADP’s five-year plan involved informing conservative organizations across Virginia about its abolition efforts and urging constituents and lawmakers to consider possible alternatives to the death penalty. Obtaining the support of the Virginia Federation of Republican Women was critical, explained Michael Stone, who credits the organization with connecting VADP with Rotary Clubs, Knights of Columbus Groups, and Kiwanis Clubs to deliver the abolitionist message. Consequently, as more and more Virginians became aware of shortcomings in the administration of the death penalty, Republican groups that once opposed abolition efforts became neutral on the death penalty, with the exception of the Virginia State Police Association, which remained wedded to its support of capital punishment.

Yet, the VADP’s targeted advocacy cost it several donors who opposed embracing conservatives into the abolitionist cause. This presented a major challenge for VADP, since it is dependent upon the sponsorship and financial support of donors to operate. Indeed, the ability to retain major donors while recruiting Republicans, or anyone else with whom those donors may disagree with, stands as a chief challenge for abolitionists. This is especially true in the American South, where Republicans – who are often inclined to support capital punishment – maintain an undeniable grasp on the region.

In the Virginia General Assembly, there was (initially) a laudable amount of Republican support for death penalty abolition founded upon ‘pro-life’ beliefs, wholly distinct from the racial dimensions on which many legislators had centered their abolitionist arguments. Senator William ‘Bill’ Stanley had originally posited his argument against the death penalty when he delivered an impassioned speech, proclaiming his reverence for the sanctity of life, during the debate of a bill designed to expand access to abortion in 2020. While such a speech was to be expected from an ardently Republican lawmaker, listeners were surprised to hear Stanley apply his ‘pro-life’ logic to the death penalty. In Virginia, it was the first time that any current Republican legislator had voiced their opposition to the death penalty, and it proved effective for garnering a smattering of votes.

Yet Stanley ultimately made his support contingent on those convicted of aggravated murder receiving life without parole (LWOP), a ‘mandatory minimum’ that Dale Brumfield asserted “torpedoed [Stanley’s] entire pro-life argument.”[5] It was ironic that Stanley’s advocacy, the linchpin of Republican support for the abolition bill, would ultimately rest upon his insistence for LWOP as the alternative to, or replacement for, the death penalty, because he had previously called for his colleagues to be consistent in their voting for life:

And if we’re going to be consistent, if we’re actually going to be human and consistent, then we all should take one position that is consistent. Don't vote for a life bill, and then vote against the death penalty bill. Make sure morally, legitimately, that we have a policy here in Virginia that is consistent with life, because life matters.

However, the Democratic majority in the Senate was unwilling to acquiesce to Stanley’s demands, especially since such a political straddle was not necessary for a state solidly controlled by the Democratic Party. This decision came in response to inner-party turmoil over mandatory minimums: there was substantial disagreement between Democrats over whether all, some, or any of the 224 mandatory minimum offenses in Virginia should be repealed. Legislators who supported the elimination of these laws argued that they disproportionately impact Black defendants, challenge judicial discretion, and fail to deter crime.

Despite their disagreements, the Democratic lawmakers proceeded unilaterally on the abolition of the death penalty because (1) they had the votes for abolition without any Republican consensus, and (2) they were unwilling to create an additional mandatory minimum, especially one as similar to the death penalty as LWOP. Though LWOP is often touted as an acceptable alternative to the death penalty by abolitionists and tough-on-crime conservatives, scholars have argued that LWOP is a ‘hidden death sentence’ since it stresses the incorrigibility of offenders and is not treated with the same urgency as death sentences, thereby impacting the likelihood, or timeliness, of remedying a wrongful conviction and racial bias.

What this means is that the abolitionist methodology that succeeded in Virginia would have to undergo some tinkering in order to carry over into other states that retain the death penalty. The most important lesson that Virginia’s experience teaches us about death penalty abolition lies where its repeal efforts could have succeeded: abolition was originally a bipartisan proposal, but Virginia Democrats willingly sacrificed bipartisanship to secure life with parole rather than another mandatory minimum (i.e., to maintain the values they support). Similarly, VADP donors refused to work with conservatives because of differences in political ideology. Therefore, abolitionists must work with Republican legislators going forward, given their prevalence in retentionist jurisdictions, and attempt to meet them halfway. Abolitionists must also consider the ascent of the pro-life argument, while observing constituents’ reactions to proximal triggering events and making the most of legislators’ willingness to respond. Lastly, an alternative to the death penalty must be found – one that Democrats and Republicans are both willing to accept.

|

Aimee Clesi is an MPhil candidate in Criminology and Criminal Justice under the supervision of Professor Carolyn Hoyle, Director of the DPRU. Aimee has worked at every level of the judiciary in Florida, including the State Supreme Court and Federal Trial Court, and aims to challenge wrongful convictions and the death penalty as a lawyer in the American South. Her current research examines the legislative and civil society conditions necessary to galvanize states toward abolition de jure, especially following a period of abolition de facto status. |

[1] Nearly every state that has legislatively abolished capital punishment in the modern death penalty era has had a Democratic trifecta, except for Nebraska and New Hampshire. In these states, Republican governors vetoed abolition legislation, but legislative majorities overruled each veto. However, in Nebraska, the death penalty was later reimposed by a citizens’ ballot initiative in 2016, against the will of its unicameral, Republican-led state legislature.

[2] Interview with the author.

[3] Interview with the author.

[4] Interview with the author.

[5] Interview with the author.

Photo credit for listing image: MBandman via Flickr, licensed under Creative Commons CC BY 2.0 DEED.

Keywords:

Share: