In May 2023, Lucrezia Rizzelli and Amelia Inglis hosted an art exhibition at Lincoln College, University of Oxford, showcasing artworks created by death row inmates from around the world, as well as professional artists who explored the theme of capital punishment.

Art serves as a therapeutic tool in various settings, aiding mindfulness practices and fostering personal self-expression. Indeed, prison arts programmes have been found to increase self-esteem, self-efficacy, and self-confidence, as well as people’s willingness to make positive changes in their lives. Art can also be an important instrument in helping individuals process and cope with trauma, and research has found that inmates’ mental health, as well as their ability to cope with stress and complex emotions improved with their participation in artistic endeavours.

It is therefore unsurprising that within the profoundly traumatic environment of death row, art can provide a respite from the bleakness of an abruptly altered future and the severe ‘pains of imprisonment’ that characterise the lived experiences of those sentenced to death. Individuals on death row often grapple with what is commonly referred to as ‘death row syndrome’, encompassing a range of negative mental and physical consequences stemming from the extreme deprivation and anxiety intrinsic to their status as ‘dead men walking’.

For many on death row, art represents the only escape into the realm of imagination, a way to transcend the four walls of the cell and reconnect with nature or a happier past self. A 2021 study by Danielle Littman and Shannon Silva reports that inmates participating in arts programmes found solace in the creation process, stating that it made them feel like ‘human beings rather than caged animals’ and like they were ‘alive, if only for a moment’. This theme prominently emerged in the artworks in the exhibition ‘Voices from Death Row: Art as a Form of Expression’.

For many on death row, art represents the only escape into the realm of imagination, a way to transcend the four walls of the cell and reconnect with nature or a happier past self. A 2021 study by Danielle Littman and Shannon Silva reports that inmates participating in arts programmes found solace in the creation process, stating that it made them feel like ‘human beings rather than caged animals’ and like they were ‘alive, if only for a moment’. This theme prominently emerged in the artworks in the exhibition ‘Voices from Death Row: Art as a Form of Expression’.

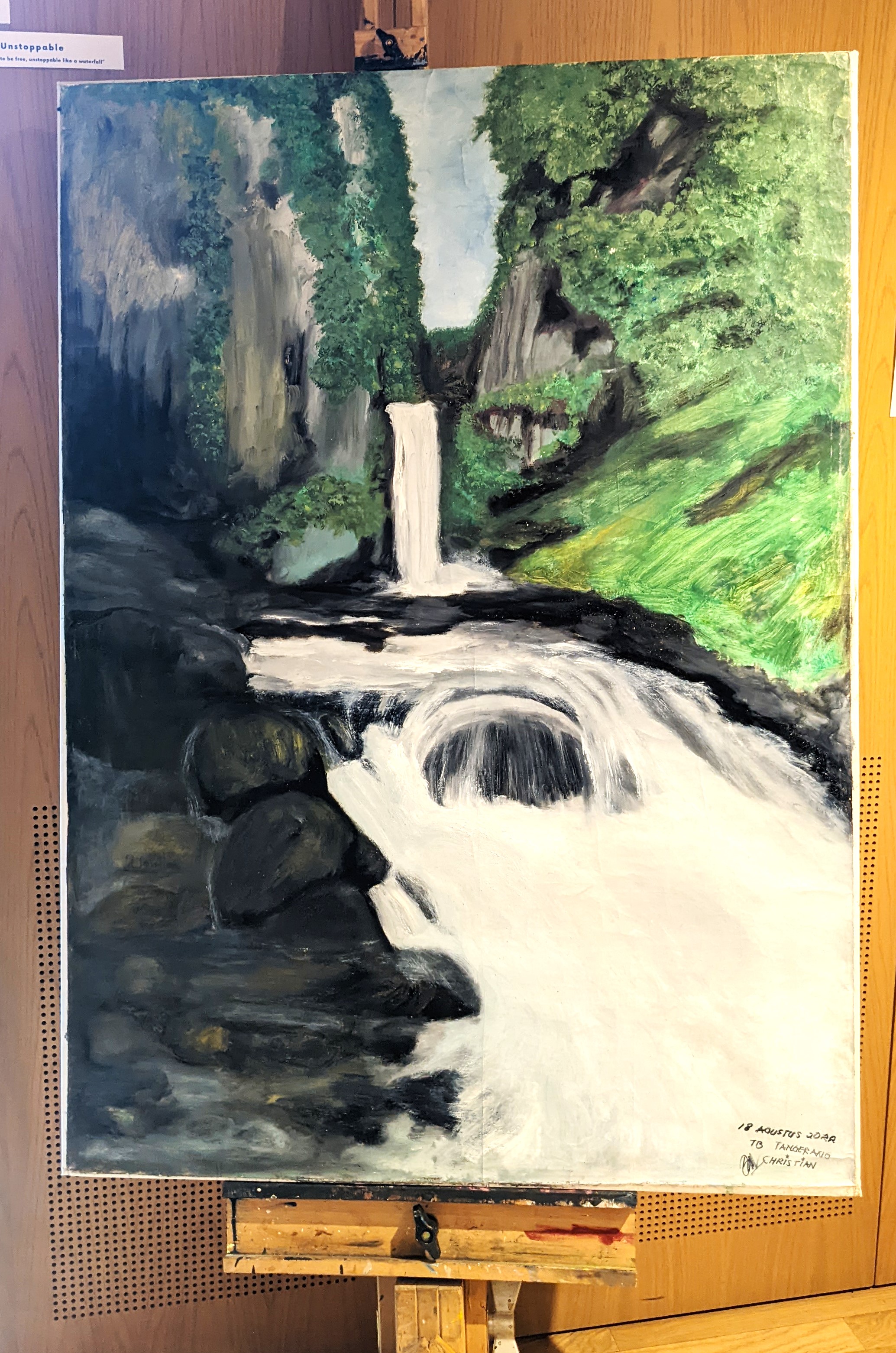

The organisers, Amelia Inglis and I, were determined to shed light on these inner worlds created by individuals whom society had often deemed as beyond redemption. For instance, one death row inmate, incarcerated in Jakarta for a drug offence he insists he did not commit, chose to depict familiar places from his past, wildlife, and natural landscapes, as the central subjects of his art. His intention was to capture the world beyond the confines of death row. Similarly, a death row inmate in Louisiana sent us a drawing featuring vibrant birds perched on a tree. In these cases, art can offer an approved ‘escape’ from a grim reality, and render ‘doing time’ less arduous; additionally, the production of ‘good art’ can enhance one’s status within the prison.

Upon receiving these nature-inspired artworks, we became acutely aware that, for some individuals, this choice of subject was not merely an artistic preference, but also a necessity to remain inconspicuous and avoid unwanted attention from both prison authorities and the public. In multiple jurisdictions, the practice of capital punishment has been criticised for its arbitrariness, with certain segments of the population disproportionately selected for execution. As every piece of artwork from prison is meticulously inspected, addressing controversial themes or advocating against the death penalty or societal issues could increase one’s likelihood of facing execution.

This leads us to the second objective of this art exhibition: activism. Capital punishment is not a commonly discussed topic in the United Kingdom, or Europe at large. Yet 56 countries worldwide still retain it as a punishment for ordinary crimes, with many of these nations sentencing individuals for crimes that most legislations would not classify as the ‘most serious of crimes’ (i.e. drug offences, ‘enmity against God’). Consequently, the death penalty risks appearing foreign to the many countries that have abolished it, and discussed primarily in abstract terms related to risk, crime management, and financial burden. This exhibition, instead, amplified the voices of death row inmates, focusing on the human element rather than the crimes for which they were sentenced.

Some of these artists used their works to protest their punishment and reaffirm the unjust nature of the criminal justice system. One exonerated death row inmate from the US, Ndume Olatushani, presented us with a painting composed of newspaper clippings about capital punishment, and the words ‘Abolish Now’ on a bright yellow background, as well as a semi-abstract god-like figure presiding over the entire canvas. A Kenyan artist juxtaposed paintings depicting routine prison life with jarring images of a person who had hung themselves in a prison cell. Likewise, scholar Valentine Cuny-Le Callet shared prints of her correspondence with a death row inmate in the US, shedding light on the controversial nature of creating art in prison and the constraints imposed by an institution designed to restrict individuals both physically and mentally.

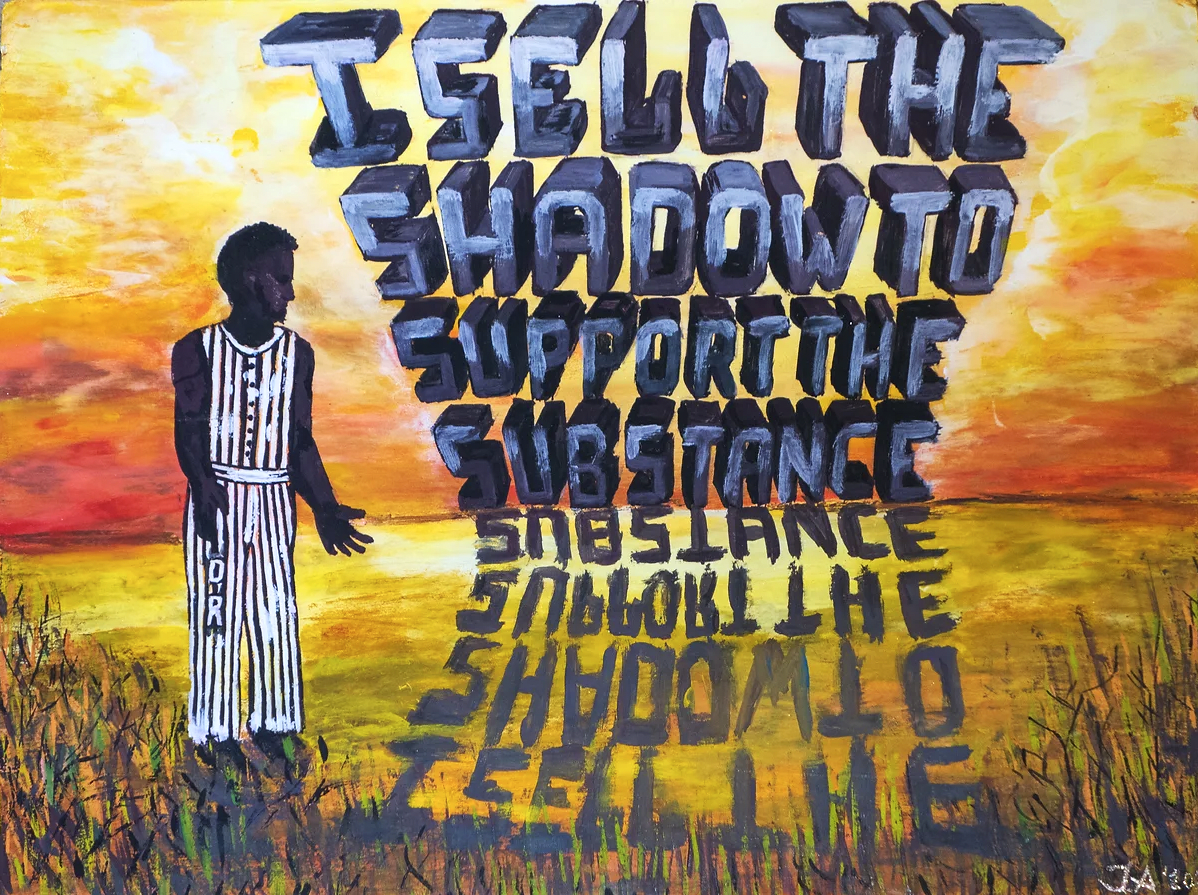

Finally, we showcased prints by Terence Andrus, who tragically took his own life in prison in Texas in January 2023, after being denied his final appeal. His art delves into the social and racial hierarchy which stratifies our society and quotes the words of the renowned nineteenth-century feminist and antislavery activist Sojourner Truth: “I sell the shadow to support the substance.” These words allude to Truth’s ability to sell her own image (a portrait), in contrast to her past when she “used to be sold for other peoples’ benefit” during enslavement. These themes are echoed by Terence, who represented himself in his prison uniform standing next to mirror images of the quote, a man owned by the state who uses his art to reappropriate his own image and identity.

Finally, we showcased prints by Terence Andrus, who tragically took his own life in prison in Texas in January 2023, after being denied his final appeal. His art delves into the social and racial hierarchy which stratifies our society and quotes the words of the renowned nineteenth-century feminist and antislavery activist Sojourner Truth: “I sell the shadow to support the substance.” These words allude to Truth’s ability to sell her own image (a portrait), in contrast to her past when she “used to be sold for other peoples’ benefit” during enslavement. These themes are echoed by Terence, who represented himself in his prison uniform standing next to mirror images of the quote, a man owned by the state who uses his art to reappropriate his own image and identity.

In conclusion, this exhibition emerged from the imperative need to establish a channel of communication between death row inmates and the general public. It aimed to amplify their voices, highlighting the role of art as a lifeline in their lives, and demonstrating art’s potential to inform audiences about the horrors and barbaric nature of capital punishment.

Share: