Resisting Radicalisation: A Critical Analysis of the UK Prevent Duty

Guest post by Anne-Lynn Dudenhoefer

On the reasons why we should not silence controversial opinions

Posted:

Time to read:

What is Prevent?

In response to the threat of terrorism and radicalisation, the Home Office introduced the Prevent strategy, which plays a key role in the government’s fight against terrorism. One of the four strands (‘Prepare, Prevent, Protect, Pursue’) of the Home Office’s counterterrorism strategy CONTEST, the Prevent strategy dates back to 2003 and is specifically tailored to avert radicalisation in its earliest stages. However, despite this broad remit, Prevent has sparked controversy over its predominant targeting of British Muslims. In 2011, the Home Office determined three primary objectives of the Prevent strategy:

respond to the ideological challenge of terrorism and the threat we face from those who promote it;

prevent people from being drawn into terrorism and ensure that they are given appropriate advice and support; and

work with sectors and institutions where there are risks of radicalisation which we need to address (Home Office, 2011: 7)

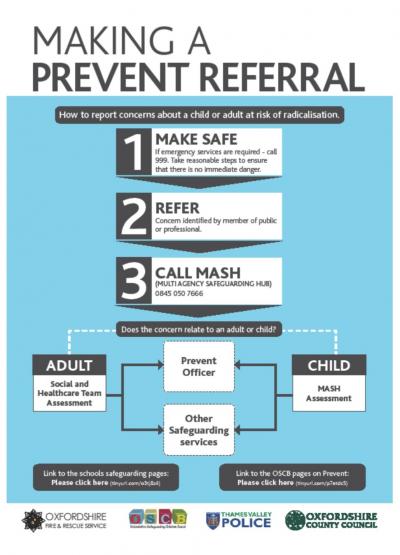

Primarily understanding radicalisation and terrorism as related to ideology, the Prevent strategy is inextricably tied to the notion of vulnerability: individuals are stripped of their agency, and portrayed as passive subjects consistently at risk of being drawn into extremism. Radicalisation is conceptualised as an ideological process, which can therefore be identified and stopped in its tracks. This intervention occurs in the following manner: if individuals are perceived to be at risk of radicalisation, they have to be referred to the local Channel board, consisting of school representatives, social workers, chairs of local Safeguarding Children Boards and Home Office Immigration as well as Border Force officials (Home Office, 2015). As part of CONTEST, the Channel board will then review the referral and decide if further action is necessary.

(Sources: ACPO, 2014; NPCC, 2016).

It is clearly evident that the Channel referrals have been subject to a significant increase from 2012 to 2016. In addition, the referrals reported as ‘International Terrorism’ are significantly higher than all other referral groups – with the exception of 2015/2016, where the ‘Under 18’ referrals were equally substantial (and presumably overlapping with the ‘International Terrorism’ category). Data on the second half of 2016 as well as the first half of 2017 could unfortunately not be retrieved – I placed a Freedom of Information request (FOI) inquiring about the referral numbers for 2016 and 2017, which got rejected by the National Police Chief’s Council (NPCC) due to reasons of national security.

In spite of this inconvenience, the data clearly illuminates the need for further analysis on Prevent’s impact on British Muslim adolescents, the classroom as well as freedom of speech. For the individual at risk of radicalisation, the consequences of a referral can range from continuous surveillance or psychological treatment to physical relocation. Evidently, the consequences can impact people’s lives significantly. While the overall Prevent strategy is already subject to severe criticism, I wish to highlight what I perceive as one of the most problematic parts of this strategy: the statutory Prevent Duty introduced by the Home Office in 2015.

Why critical analysis matters

Imagine being a teacher, having to assess whether your students are ‘at risk’ of being radicalised. What precisely are the signs of radicalisation in children and teenagers? How would you distinguish rebellious teenagers from potential extremists? Despite the fact that a list of relatively vague radicalisation indicators is offered by the Home Office, detecting radicalisation still requires a high level of discretion and can leave educational personnel bewildered. Especially teenagers may display behaviour that could easily be mistaken for signs of evolving extremism: while there is no apparent agreement on the “timing of changes with regard to identity formation” (Klimstra et al., 2010), researchers agree that forming an identity in adolescence is a developmental progress, characterised by several identity ‘crises’ (Erikson, 1972; Klimstra et al., 2013). Being viewed as vulnerable adolescents with ‘young minds already susceptible to feelings of frustration, anger [and] hate’ (Abbas, 2007: 4), particularly Muslim youths find themselves at the very core of the national debate about ‘Islamist extremism’ and ‘Jihadi terrorism’. A predominant focus on Muslims in combination with the Prevent Duty imposed on educational institutions brings with it a variety of intertwined issues which I believe require in-depth investigation. Against the backdrop of recent political events and with the goal of a peaceful multi-cultural society in mind, critical analyses of the government’s counterterrorism strategy may now matter more than ever before.

No shortage of red flags

In line with Peter Ramsay’s (2017) critique of the Prevent Duty, I argue that certain terminology such as ‘safeguarding’ students who are ‘vulnerable’ to extremist ideas is misleading and conveniently inflated in order to legitimise the Prevent Duty and facilitate its smooth implementation. However, the disproportionate targeting of British Muslims intertwined with the dual role of students as both at risk and, simultaneously, a risk, reveals that the Prevent Duty in educational institutions is deeply flawed in its implementation and has significant potential to further alienate and radicalise the British Muslim population. By definition, educational safe spaces are supposed to be inclusive in nature and should ideally encourage classroom debates. Schools and teachers ought to provide a sheltered space where students can feel safe to discuss controversial topics. Yet, the Prevent Duty offers a different kind of safe space, distinguishable by its exclusive nature. The students’ dual role of being both vulnerable and a risk, in combination with the perception of Islamist radicalism as the primary threat, creates an exclusive safe space, where students avoid raising controversial opinions due to potentially far-reaching consequences.

According to a Freedom of Information Request (FOI) published by the Association of Chief Police Officers (ACPO) in 2014, 67 percent of all the individuals referred between April 2007 and December 2010 and 57 percent of all referrals between April 2012 and January 2014 were recorded as Muslim. How many of these referrals are also categorised as ‘International Terrorism’ or ‘Under 18’ – or both – remains unclear. Yet, the comparatively high percentages of referrals of British Muslims indicate that, in practice, the Prevent strategy and Duty primarily target the Muslim population. The targeting of Muslims seems even more disproportionate considering the fact that, according to the 2016 Annual Population Survey for England and Wales published by the Office for National Statistics, only 5.6 percent of the English and 1.5 percent of the Welsh population reported their religion as Muslim in 2014.

Suggestions

The question of how to address radicalisation is more relevant than ever in the aftermath of terror attacks such as Paris in 2015, Brussels in 2016, and the more recent attacks in Westminster, London (March 2017), Manchester (May 2017), London Bridge and the Borough Market (June 2017) as well as on the Finsbury Park mosque (June 2017). The threat of terrorism is real – however, it certainly will not be averted by predominantly targeting and alienating British Muslim communities. Despite the increasingly frequent occurrence of recent terror attacks in the UK, I agree with Mukhopadhyay (2007: 111) that ‘optimism should be the exhortation. And for an optimistic future, both the wider society as well as diaspora-based Muslim communities should realise that their common future would be shared’. This shared future is best secured by standing firmly for the preservation of human rights, fostering constructive and engaging dialogue and defying the illusion that terrorism can be defeated by shutting down opposing opinions. Historically speaking, one can conclude that not many problems have been solved by suppressing freedom of speech. Preventing challenging conversations is probably more likely to temporarily silence radical opinions rather than tackle their root causes.

For further inquiries, please contact Anne-Lynn Dudenhoefer.

Share: