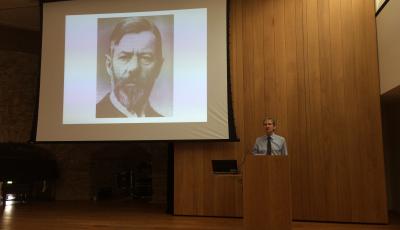

In this post, DPhil candidate Gabrielle Watson reviews the Centre for Criminology’s 50th Anniversary Lecture by Professor David Garland (New York University) and chaired by Professor Ian Loader (University of Oxford). The event was held on Thursday, 12 May 2016 at Corpus Christi College, Oxford.

Garland began by tracing the lineage―and current limitations―of historical and comparative research on American penality. A defining feature of the historical work has been its (arguably disproportionate) concern with the emergence of mass incarceration. Garland proposes to offer a challenging corrective to that scholarship by attending not only to questions of imprisonment but, instead, to the entire ‘penal apparatus’ through which individuals are indicted, excluded, controlled, and punished. Meanwhile, much of the comparative work has related differential levels of punishment to three macro-level characteristics, as detailed in the exacting accounts of Wilkinson and Pickett on inequality, Cavadino and Dignan on the welfare state, and Lacey and Soskice on political economy. Yet, Garland observed, the complex and diverse processes that link crime and punishment to these macro-level characteristics have been left largely unarticulated. In his new work, Garland will seek to articulate them.

Perhaps the most compelling aspect of Garland’s discussion was the dissatisfaction he expressed with the ways in which American penality is currently being configured. The most prominent theses―Alexander in The New Jim Crow, Wacquant in Punishing the Poor, and Simon in Governing Through Crime―variously draw attention to the political, economic, racial, and cultural factors that are implicated in America’s punitive style of criminal justice. Garland rejected these accounts in favour of an alternative understanding of the system’s nature and emergence, in which the fundamental principle is a specific form of penal power, which he terms ‘penal control.’

Of course, the argument that punishment comes in a variety of forms is well-rehearsed. It is possible, for example, to differentiate practices involving penal afflictions (capital punishment, corporal punishment, and public shaming), penal levies (the extraction of financial resources from the individual including fines, restitution, compensation, and damages), penal control (imprisonment, supervision, and disqualification), and penal assistance (correctional treatment, restorative justice, mediation, drug therapy, education, and counselling). Garland’s claim is that American penality―over the past forty years and across fifty states―has been overwhelmingly oriented towards practices of penal control. His proposed strategy is to explain American penality by reconnecting penal control to patterns of crime and violence, in a move away from other contemporary accounts that have placed explanatory weight on one factor over another. It’s a strategy that is refreshing in its breadth and ambition. This is especially so in the context of academic criminology, which is all too concerned with precisely drawn, narrowly focused accounts, to the relative exclusion of large-scale hypotheses and grand narratives.

Professor Garland will lecture again on this theme on Tuesday, 24 May at the University of Edinburgh and on Tuesday, 7 June at the British Academy.

Share: