Marion Vannier writes:

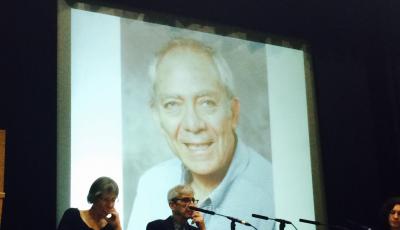

The London School of Economics (LSE) hosted an event on December 10th where Stanley Cohen’s family, friends and colleagues celebrated his works, ranging from academic research on “denial”, “social control” and “moral panics”, to activist reporting on human rights violations in Israel.

The event, chaired by Margo Picken - Cohen’s long-time friend and committed human rights researcher - saw a variety of speakers assemble from across the world. Contributions were given by his brother, Robin Cohen, his former doctoral supervisor and friend at the LSE, David Downes, his colleagues and friends, Daphna Golan, with whom Cohen wrote the first ever report on torture of Palestinians in Israel, and Harvey Molotch from NYU, and finally Thomas Hammarberg, the Former Council of Europe Commissioner for Human Rights.

These personal testimonies were extremely moving. Some, like myself, may even have felt slightly misplaced when hearing these intimate accounts. While a great number of students and researchers may have read and studied Stanley Cohen’s works, most did not know the man or personality behind the research. Therefore, these tributes provided a new lens through which to understand Stanley Cohen’s research.

Robin Cohen journeyed back to their family’s history to explain his brother’s early commitment to exploring puzzling exclusionary social reactions and to unveiling human rights violations. Stanley Cohen’s Jewish ancestors came from a small village in Lithuania. In 1941, the Lithuanian government exterminated the vast majority of Jews, giving no other choice for those who had survived but to flee the country. Stanley Cohen’s family were scattered across South Africa, America, Russia, the UK and Israel, and collectively experienced and witnessed apartheid in South Africa, the civil rights’ movement in America, the Intifada in Israel and the nationalistic rise in Russia.

Stanley Cohen’s critical thinking has been shaped by his family’s experience, by the stories he was told as child, by what he witnessed as an adult man in South Africa, Israel and in England. His family’s numerous displacements moulded his perception of “place” and “belonging”, which he viewed as intangible and permeable notions, and guided his research on cultures of exclusion and inclusion. The mass atrocities committed by different states that his family experienced, or that he directly witnessed, incited him to explore how officials use their control to govern and how they eventually deny their abuses and violations.

The suggestion that roots and academic paths are interlinked is probably applicable to many researchers. Do we not conduct research that is somehow a reflection of where we come from, what we experience? Our research possibly says more about who we are as individuals than what we might think.

In the specific context of criminology, I wonder, and ask, whether, to produce meaningful academic works, researchers can or should have experienced, witnessed or inherited, a history of injustices, exclusion and violations? To what extent can or should criminologists write about questionable punishments, the impact of sentencing on children or families, the expansion of criminal activities, police and policing legitimacy, human rights violations without having experienced, whether directly or indirectly a form of the latter?

If experience or witnessing does matter in providing a contribution to the field and a better understanding of certain criminological phenomena, is it not then necessary to conduct research close-up as opposed to thinking and analysing from a distance?

A former student of Stanley Cohen spoke about Cohen’s love for jazz. He remembers his supervisor quoting jazz pianist Thelonious Monk who once told his student that it was fine to make mistakes, but not to make ‘wrong mistakes’. Cohen encouraged his student to take chances and make ‘right mistakes’, over and over again, but warned him against making ‘wrong mistakes’, such as ‘laziness or ‘arrogance’.

Stanley Cohen’s legacy to those who did not know him in person is perhaps best understood as an invitation to get in the field and not only to “think” and analyse within the perimeters of our office walls, but to actually “search”, in its purest etymological sense. Otherwise, we are warned, we run the risk of committing wrong mistakes.

Share: