Causes of the Anglophone Conflict in Cameroon

Transcript and recording of the presentation delivered by Dr R. Willis at The Oxford Conference on US Senate Resolution 684 on 17th February 2021

Presention available to view: https://youtu.be/J2cBtAjTu9g

Posted:

Time to read:

“I’m Dr Roxana Willis, a researcher at the University of Oxford, and Principal Investigator of the Cameroon Conflict Research Group. I’ve been asked to outline ‘the root causes of the crisis’, which US Senate Resolution 684 urges the Cameroon Government to address (at paragraph 4A). I have around 7 minutes, and so a great deal is omitted. Nevertheless, I hope this offers a starting point.

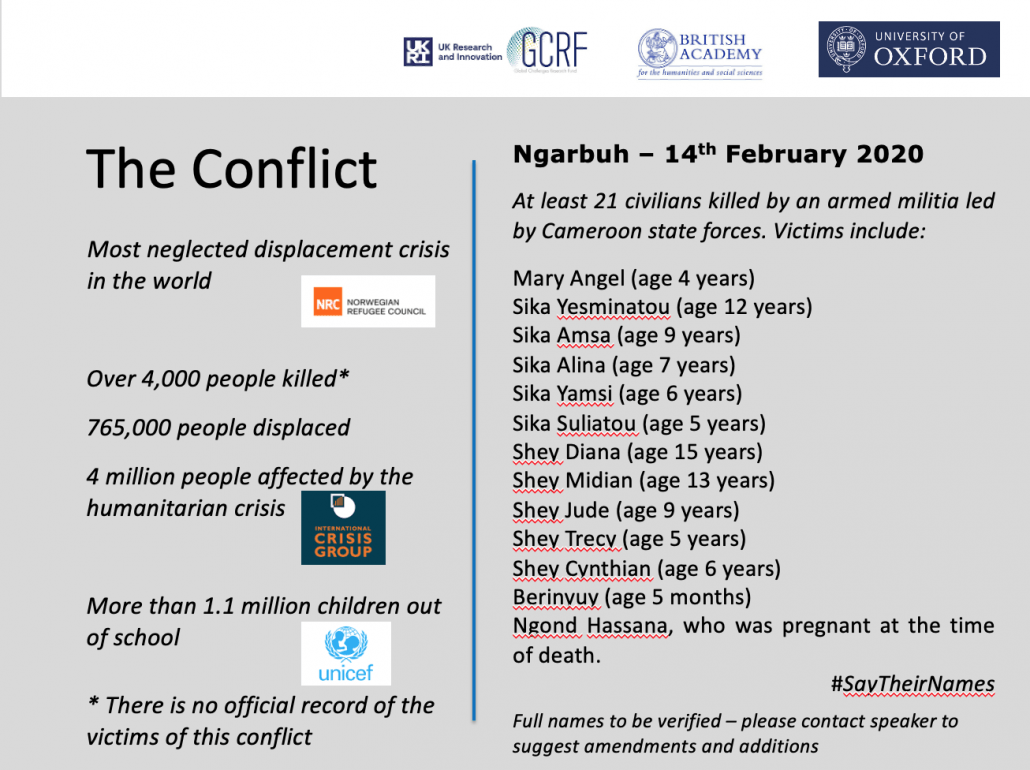

A striking feature of the Cameroon conflict is the lack of attention afforded by international actors. Despite the brutality of violence, in which children have been prime targets, international response has been worryingly minimal. US Senate Resolution 684 marks an important turning point. Hopefully other key actors will follow suit.

A visible starting point of the conflict was the violent suppression of anglophone protests by the majority francophone state.

For context, professional jobs are hard to access in Cameroon, and many suggest that they are denied opportunities because of their anglophone background. This situation worsened when francophone professionals were appointed jobs in anglophone regions. Reports emerged of judges, unable to speak English, ruling on the common law, and teachers, without knowledge of anglophone curriculums, appointed in anglophone schools.

Marginalisation of anglophone heritage, cultural activities, and ways of life led lawyers, teachers, and civilians to protest. Despite

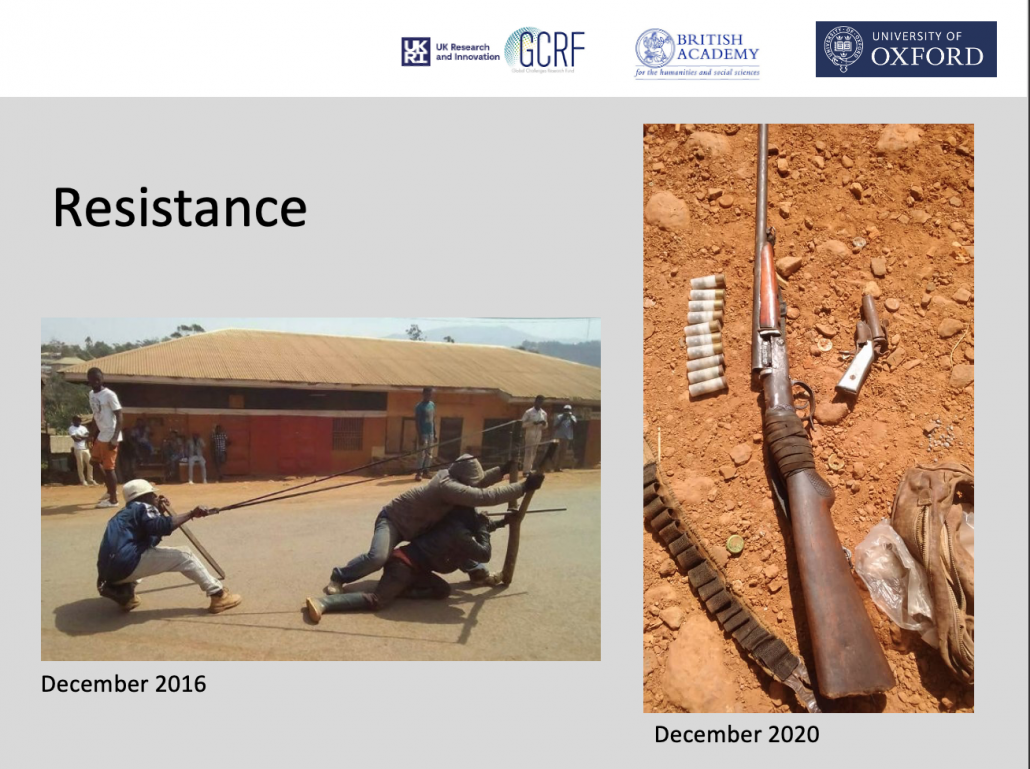

In response to unexpected violence, some anglophone groups tried to defend the local population. Initially, this began by constructing makeshift weapons. As the state violence escalated, anglophone resistance grew. A minority of civilians picked up arms and joined the violent struggle.

Many fighters rely on old hunting rifles. Even in December, a young man killed by state forces was equipped with very old weapons.

The military power of the armed anglophone groups is notably lacking compared to the military power of the Cameroon state, which is heavily backed by international actors. Over the last 10 years, the US has channelled hundreds of millions of dollars into state military forces.

Germany pays the largest sum of development funding in the world to Cameroon – €100 million between 2017-2019 alone. Germany has also conducted a four-year covert military operation in Cameroon to train the army in anti-terrorism techniques.

Since 2018, the UK government has supported the London-based firm, New Age, to win a contract to develop an offshore gas project in Cameroon estimated to be worth more than $250 million. This lucrative contract sees money going directly to the state-owned company SNH, which reportedly funds the elite armed forces of the Cameroon state.

France’s involvement in Cameroon has continued since independence and is by far the most significant. In addition to military support and trade deals, France has maintained indirect control of the local currency and has been heavily involved in the political process.

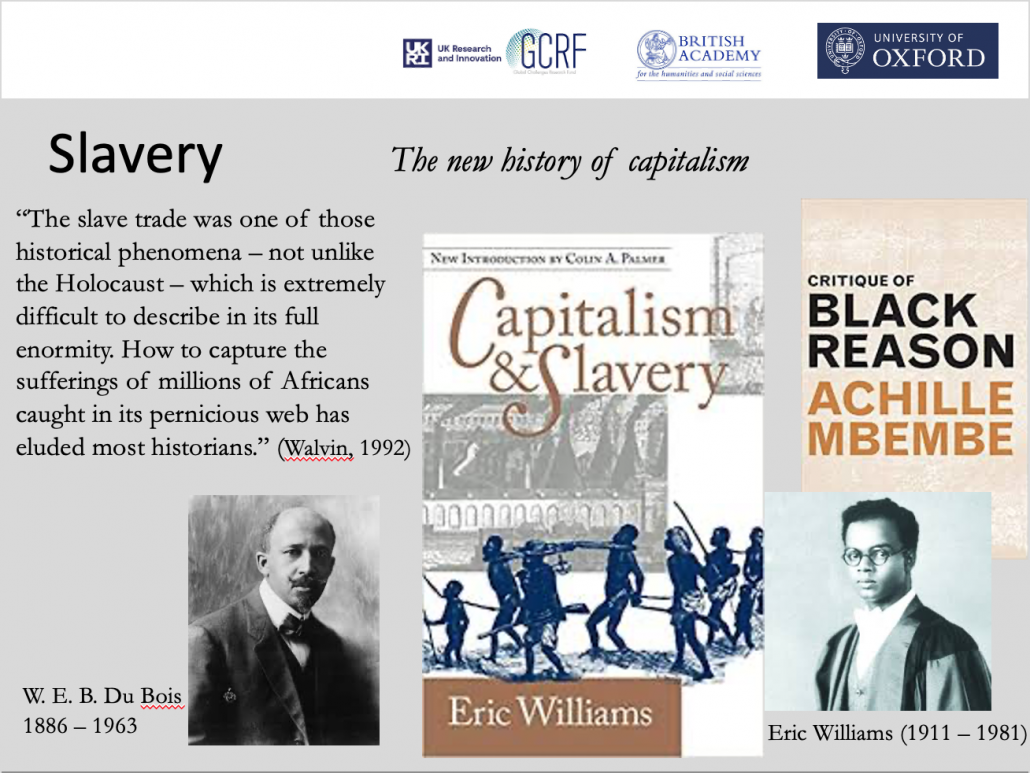

International involvement and economic dependency on the peoples of Cameroon is long running. These exploitative relationships began in the seventeenth century, when millions of African people were forcibly relocated during the repugnant trans Atlantic slave trade. This has formed the basis of relationships in modern day Cameroon.

An important body of scholarship shows how the exploitative socioeconomic structure implemented through the European legal regime of slavery continues to structure exploitative relationships in the present, albeit in transmuted forms.

Slavery informally continued in Cameroon during the colonial rule of Germany, France and Britain. During the second phase of colonialism, the French and British forces haphazardly divided Cameroon, with France taking control of a larger share. France and Britain then each implemented a range of cultural institutions which fuel the conflict we see today.

Resistance against European exploitation has been a long running feature of West African and Cameroonian history. From uprisings against slave traders on the ships, to rebellions in the fields, and full-scale revolution.

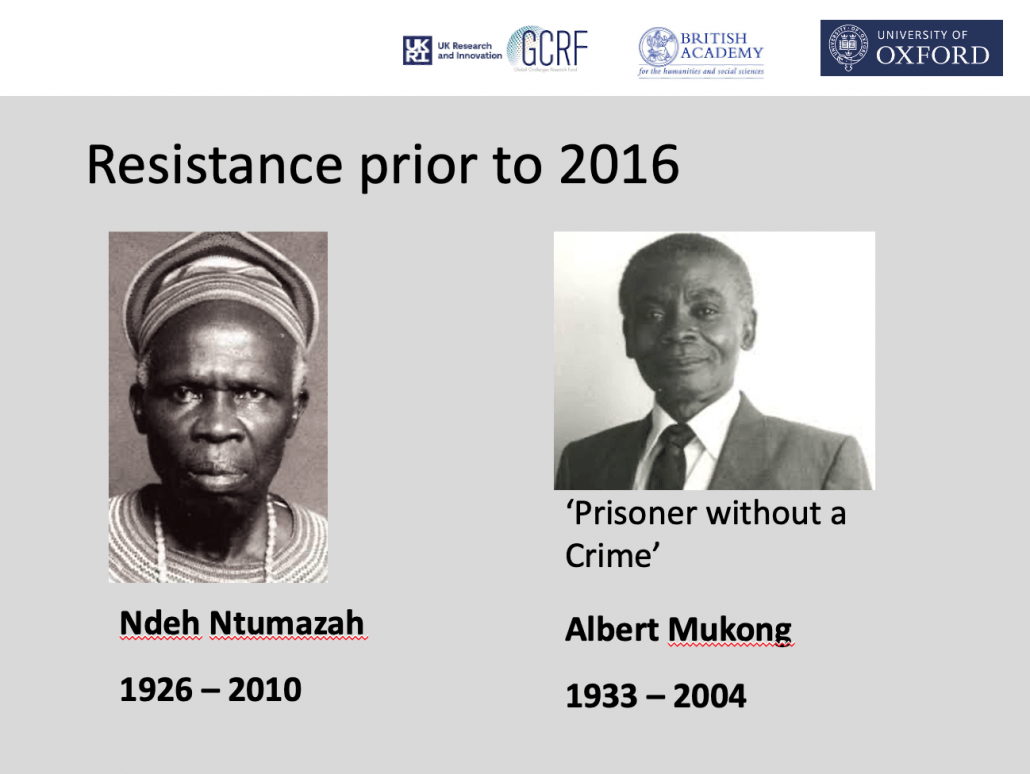

There are many notable figures in the anglophone struggle against oppression, two of which I mention here. For many years, Ndeh Ntumazah attempted to make the international community open its eyes to the plight of anglophone Cameroonians. And the human rights activist, Albert Mukong, dedicated his life to challenging the marginalisation and mistreatment of southern Cameroonians.

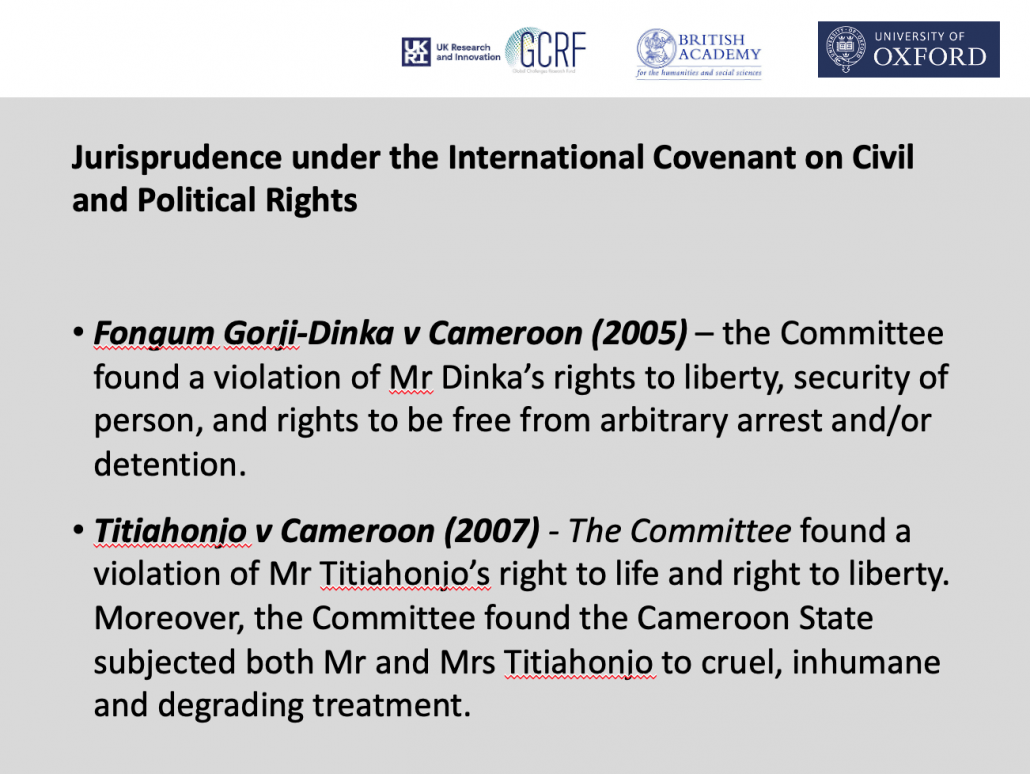

In addition to petitioning local and international communities, anglophone Cameroonians have also exhausted legal avenues in the struggle. This includes pursuing numerous human rights cases at the level of the United Nations, which has resulted in the creation of a rich body of jurisprudence that documents sustained and extreme state violence against the anglophone peoples.

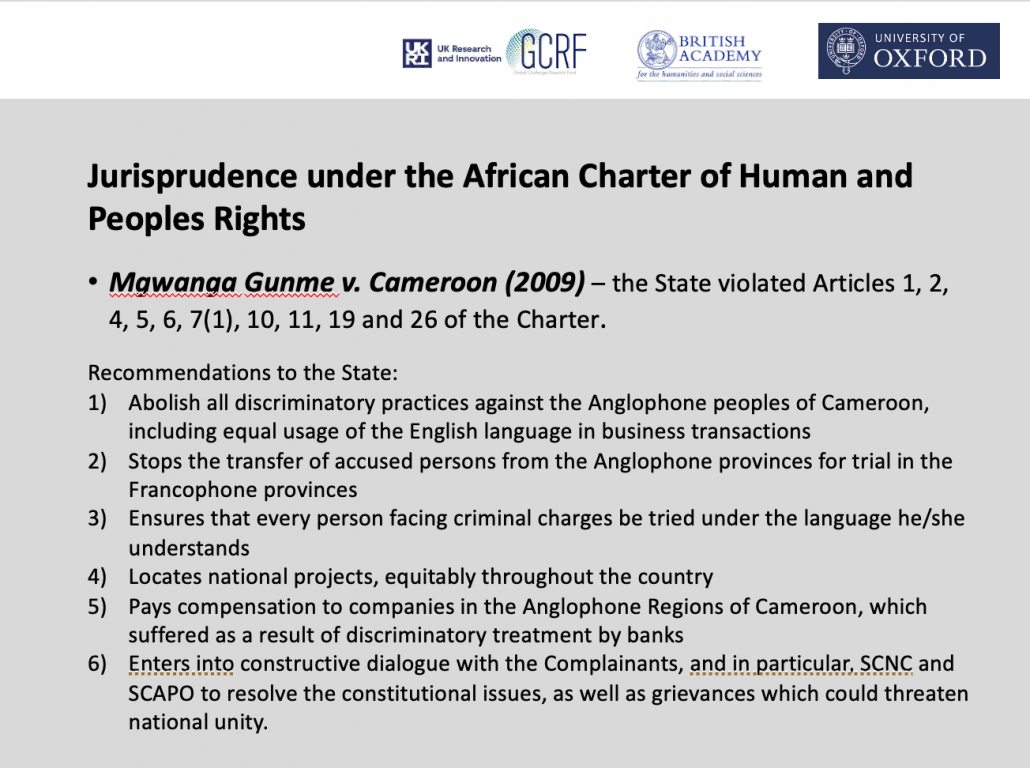

Moreover, regional jurisprudence has also been developed by anglophone activists. The 2009 judgement by the African Commission on Human and Peoples Rights anticipates the current conflict. Here, the commission urges for dialogue, calls on the state to end discriminatory treatment against the anglophone minority, and appeals for legal proceedings to take place in anglophone regions and in a language understood by the accused, among other recommendations.

To conclude, the root causes of the Cameroon conflict are multilayered and complex. Relationships between anglophone civilians, the Cameroon state, and international state actors have largely been exploitative and infused with power imbalance. Unfortunately, these relationships continue into the present. Despite gross inequalities, and centuries of being ignored, the anglophone peoples of Cameroon continue to resist and strive for a long overdue freedom.

In 2021, the discussion we should be having is about reparations and apologies for centuries of wrongdoing. Instead, we’re witnessing wealthy nations willingly ignore mass atrocities in order to bite more of the pie. This is adding to a growing moral debt that will one day need to be repaid.”

Selected bibliography:

- Asong, L., Chi, S. N., (2014), Ndeh Ntumazah: A Conversational Auto Biography, African Books Collective.

- Du Bois, W. E. B., (2014) [first published in 1896], The Suppression of the African Slave-Trade to the United States of America, Oxford University Press.

- James, C. L. R. (2001), The Black Jacobins: Toussaint L'Ouverture and the San Domingo Revolution, Penguin UK.

- Mbembe, Achille, (2017), Critique of black reason, Duke University Press.

- Mukong, A. W, (2009), Prisoner without a Crime. Disciplining Dissent in Ahidjo's Cameroon: Disciplining Dissent in Ahidjo's Cameroon, African Books Collective.

- Williams, E. (2014) [first published 1944] Capitalism and slavery, UNC Press Books.

Share: