FinTech-Bank Partnerships in China’s Credit Market: Models, Risks, and Regulatory Responses

Posted

Time to read

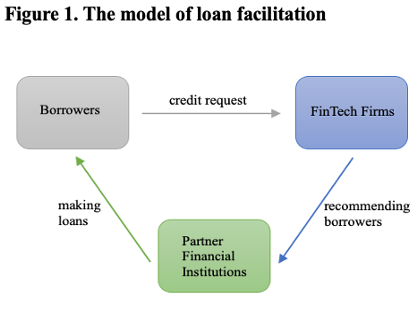

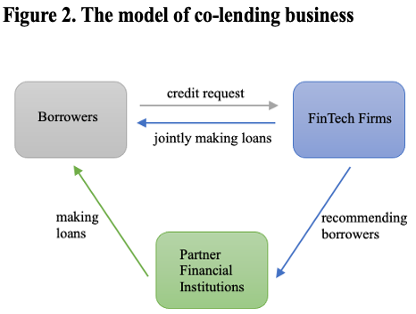

Information technology has disrupted the traditional way of providing financial services and products in recent years. China is one of the pioneers in developing new models for banking services through partnerships between FinTech and financial institutions. The two main models of FinTech-Bank partnership are loan facilitation and co-lending. Loan facilitation refers to FinTech firms providing financial institutions with technical support and credit-related services. Under the model of co-lending, apart from the provision of ancillary services, FinTech firms also contribute some funds to make loans together with their partner financial institutions. Our paper takes FinVolution Group and Ant Group as examples to illustrate the two business models of FinTech-bank partnership (see figures below).

By establishing business partnerships, FinTech firms can leverage massive customer data and innovative platform technology to provide important assistance for financial institutions at some key junctures of the lending process, thus improving access to finance. The collaboration with FinTech firms enables financial institutions to concentrate on their core business by outsourcing certain work and serve their customers with greater efficiency. On the other hand, FinTech firms can take advantage of the funds, expertise and resources of financial institutions to engage in credit-related business without the need to apply for a separate license. The partnership with financial institutions can also bring reputational benefits to FinTech firms and strengthen their brand image in the credit market.

While FinTech-Bank partnerships may bring many benefits to China’s credit market, they also pose serious risks and problems. Firstly, the collaboration with FinTech firms will increase the operational complexity of financial institutions. FinTech firms are not subject to stringent financial regulations. Hence, a challenge for financial institutions lies in their ability to deal with outsourcing risks arising from misconduct of their partner FinTech firms. Secondly, the exclusive control over data and technology is likely to reinforce the monopolistic practices of FinTech firms, thus leading to vendor lock-in problems for their partner financial institutions and customers. Thirdly, as FinTech-Bank partnerships involve the processing and sharing of vast amounts of customer information, there are growing concerns regarding data security and privacy issues. Further, FinTech firms risk making loans to customers based on inaccurate credit assessment due to the input of biased data and the defective design of algorithmic models. Last but not the least, financial institutions may face greater risks in relation to outsourcing activities, data security and algorithms if the provision of such services is dominated by a few FinTech firms. The operational failure or cybersecurity incidents of dominant FinTech firms can easily have systemic effects.

China has endeavored to address these problems by strengthening various areas of law, such as anti-monopoly law, data protection law and financial law. Specifically, antitrust regulators have issued guidelines for the platform economy sector to prevent monopolistic practices and safeguard customer interests. China has further consolidated its regulatory regime for data security and privacy protection to tighten oversight of FinTech firms’ business. The central bank has also formulated industry standards to ensure the security, explainability and accuracy of algorithms in innovative financial applications. Our paper focuses on the particular issue of outsourcing activities. China has adopted different regulatory mechanisms for the two models of FinTech-Bank partnerships. With regard to the co-lending business model, FinTech firms are required to apply for a credit business license from the financial regulator. However, there is a loophole in the existing regulations. In practice, unlicensed FinTech firms can make loans to customers indirectly by investing in trust schemes managed by their business partners. We thus suggest closing the loophole by clarifying that the relevant licensing requirements apply equally to direct and indirect participation in co-lending activities. As to the loan facilitation model, FinTech firms do not need to hold a credit business license, but rather simply ride on the license of their partner financial institutions. It gives rise to more complicated challenges, since reliance is unduly placed on financial institutions to oversee their partner FinTech firms and be ultimately responsible for the performance of outsourcing services.

The regulation on the loan facilitation model gives rise to more complicated challenges, as reliance is unduly placed on financial institutions to oversee outsourcing activities conducted by their partner FinTech firms. Drawing upon the experiences of some overseas jurisdictions, including the US, the UK, the Netherlands, Luxembourg and Switzerland, our paper argues that China can adopt a staged and differentiated approach to regulate FinTech-Bank partnerships. The first step is to create a regulatory sandbox for FinTech firms to test their innovative business. As FinTech firms need time and resources to meet relevant sandbox requirements, China may also consider introducing an umbrella regime, under which FinTech firms can provide trial services and products under the shelter of an umbrella entity. After FinTech firms complete the sandbox process and proceed to operation, the key issue becomes the continuous supervision of their partnership with financial institutions. China is advised to implement a sophisticated licensing regime to set out differentiated rules for FinTech firms according to the nature and types of services they engage in. In this regard, more categories of special licenses can be created as ‘limited licenses’ as distinct from the traditional ‘full licenses’ to address the problem of regulatory arbitrage. Further, it is worth experimenting with a mentorship scheme, under which the monitoring responsibility of financial institutions is limited to compliance violations of their partner FinTech firms. This idea emphasizes the value of the help and advice that financial institutions provide to FinTech firms, especially those in the early stage of development. For more established FinTech firms, the special licensing regime can be used to ensure effective oversight.

Robin Hui Huang is Chair Professor at the Faculty of Law, Chinese University of Hong Kong.

Christine Menglu Wang is Post-doctoral Fellow at Faculty of Law, The University of Hong Kong.

Share

YOU MAY ALSO BE INTERESTED IN

With the support of