San Antonio’s events were bound to happen. It was just a matter of time.

Posted

Time to read

Starting in mid-April, local newspaper and television channels in the border city of Laredo, Texas, began to report the local sector of US Customs and Border Protection (CBP) was noticing an increase in the cases of people being smuggled through the local checkpoint onboard of trailers. In fact, the very day of the event in San Antonio that took 53 lives, CBP Laredo reported through its Facebook page that that weekend they had encountered over 400 people being transported in the back of trailers in six separate attempts.

Every year towards the end of the Spring and the beginning of the summer, there is an increase in the number of irregular crossing attempts along the US Mexico border. Most policy makers and commentators tend to singlehandedly attribute spikes to migration control and policy. But on the US Mexico border, any seasoned border patrol agent will quickly dismiss those claims, pointing out to the correlation between apprehensions and weather patterns. While certainly, for the last two years the US Mexico border has remained closed to people seeking to apply for asylum under Title 42 regulations, those seeking to cross the border irregularly with the hope of finding employment continue to rely on the services of smuggling facilitators, as there are no legal paths for them to migrate with that purpose. In fact, initial findings suggest that most of the people riding the trailer to San Antonio had left their communities recently, and not with the purpose of filing asylum claims.

This is the time of the year when as we drive along South Texas highways, we come across people emerging from the ranches, sitting by the side of the road, disoriented and defeated in their attempts to cross. US CBP crews, the US National Guard, or the Texas highway patrol (known locally as Troopers) document the incidents in their social media pages. The same way we gather to talk about the weather, as locals we comment on immigration chases happening along the highways connecting Laredo to San Antonio, and on the raids taking place in the smaller towns by the Rio Grande like El Cenizo, San Ygnacio or Zapata, where smuggling facilitators –all local residents –are known to operate.

South Texas and the ever-present feel of migration control

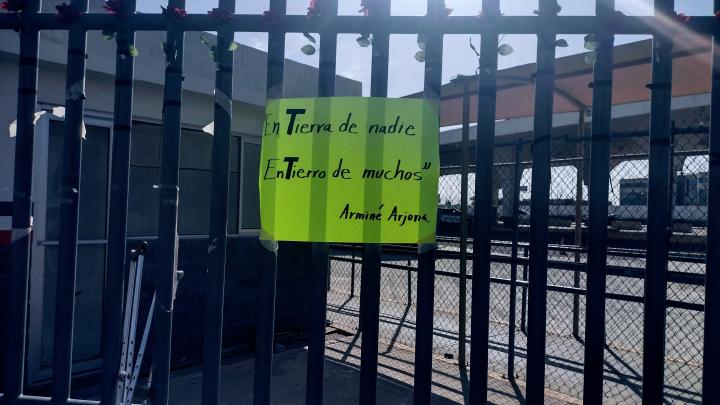

The people who perished in the San Antonio accident most likely boarded the trailer that transported them in the city of Laredo, one of the main ports of entry for goods into the United States. It would have been unlikely for smuggling facilitators to bring across the actual border a group of people of that size given the intensity of US Customs’ inspections and controls. Media reports suggest people were indeed transported from indigenous villages, cities and towns in Honduras, Guatemala and Mexico to Nuevo Laredo (Laredo’s sister city on the Mexican side of the border) and to other neighboring communities on both sides of the Rio Grande. Once the entire group was in Laredo, they boarded the trailer that intended to take them to San Antonio, and from there to other destinations across the United States.

Compared to its neighbors, Laredo is not big in terms of migrant apprehensions. In fiscal year 2022, the Laredo Sector of CBP has reported only 77,684 encounters, making it the sector with the lowest number of encounters in South Texas. It is low when compared to neighboring Del Rio (location of the now infamous incident involving Haitian migrants in 2021) with 280,622 encounters, and Rio Grande Valley, which in the same term has reported 333,224.

This does not mean Laredo is a stranger to enforcement. CBP is one of the main and largest agencies in the entire South Texas region. In fact, it was a branch of CBP the one that responded to the tragedy in Uvalde, another neighboring town, only a few weeks ago. CBP’s presence can be seen and feel everywhere, with vehicles patrolling our streets, parked outside of supermarkets, and even helping stranded drivers in the heat of the summer. Visitors have asked if I am not bothered by the sound of CBP helicopters hovering my house at night.

CBP is also one of the main employers in our border communities, where poverty and unemployment levels are among the highest in the country. It should not come as a surprise that most university students aspire to join the agency in a region with limited access to quality employment options. Nor that smuggling migrants and drugs becomes a source of income for the many more pushed out of the local education and employment system. The only capital many of the men and women involved in smuggling have is their knowledge of the roads that connect this land of vast ranches and hunting grounds, places they have known from childhood. While smuggling may generate important sums of money, it is quite often seasonal and temporary, and not enough to help them get by.

Smuggling is neither sophisticated nor complex

A few days after the tragedy, US Department of Homeland Security Alejando Mayorkas stated that one of the reasons the truck carrying the migrants had not been stopped at the Laredo checkpoint was the increasingly sophisticated strategies that smugglers have developed over time in order to avoid detection.

Ironically, the claim of smuggling becoming increasingly sophisticated is not new. Border scholar Peter Andreas first referenced it in regards to pricing in the original edition of his influential book Border Games, which suggests the concept has endured for at least 20 years.

It is important to reflect on what “sophistication” in smuggling meant to Andreas, and how it is commonly used. During the pandemic, several reports by international organizations and think tanks often relied on the term, saying the slowdown gave smuggling gangs the opportunity to regroup and expand their operations relying on more sophisticated ‘tools’. At academic and policy events I often hear colleagues use the term in reference to smugglers alleged reliance on complex, expensive, or advanced technology. I have myself been asked during recent interviews to speak about smugglers’ use of the dark web, bitcoin or even artificial intelligence as indicators of their sophistication.

The initial investigation to what happened in the San Antonio incident suggests that people had been sprinkled with a pungent spice with the hope of avoiding detection by the K-9 team. Over the years people I have interviewed have described covering with construction lime or with pepper for the same effect. My own family members have narrated stories of dressing in camouflage to blend with the colors of the desert. If at all, smuggling techniques are quite unrefined, not sophisticated.

Even the linear claim that stepped-up enforcement leads smuggling groups to become more sophisticated what in turn leads to higher fees does not hold entirely true from my experience. The increase in costs can be explained part inflation, part the growing numbers of people smuggling fees are split among, which include not only the increasing numbers of facilitators people must rely on to get to a destination, but also the exploding numbers of law enforcement officers in origin, transit and destination countries assigned to migration control. Countering smuggling has created important sources of income for law enforcement agencies worldwide. Enforcement is only one element of the equation. I find it disingenuous that the way states profit legally and extralegally from counter-smuggling activities is hardly ever part of the complexity or evolution narrative policy makers and scholars like to speak about.

What happened in San Antonio will happen again.

Almost a week after the events in San Antonio, I drove to the site where the trailer carrying the migrants was found. It is not easy to access. It is in the outskirts of the city, in a section I am sure most San Antonians have not even heard of, on a road covered with piles of burned trash against signs that say “Don’t be a fucking litter bug.” Once the dirt road ends one must drive into what looks like a private if unattended alley next to the railroad tracks. Its lack of easy access makes it a perfect spot to drop off a group of people undetected.

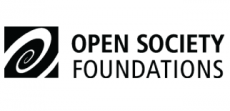

But people found it. On Sunday morning there were hundreds of them at the site. They were not journalists –most have left, most likely scared away by the high temperatures of South Texas, which on that day alone reached 38 degrees. There were no signs of any officials having stopped by recently. Those arriving were migrants themselves, men and women of all ages and their children and grandchildren descending from beaten up cars and big Texan trucks showing the signs of hard construction and agricultural work. They were carrying flowers, hand-painted signs, flags, candles, bottles of water and Gatorade. They brought balloons, stuffed animals, religious images. I was struck by the number of men depositing flowers at the feet of the crosses – 53 in total – that were installed by the Honduran diaspora in San Antonio. Some of them were crying. Others were standing in small groups next to their trucks in silence, that same silence I remember seeing in the faces of my uncles and grandfather after the passing of a close friend or loved one.

We were brought together by the collective grief we felt over the deaths – there was something in them that reminded us of our own journeys across the border. Of our families and their fears. Of the pain known too well of losing a loved one to the violence of border enforcement and control. People were speaking about their own journeys, about how they had barely made it out alive. But I think we were also brought together by the realization that the occurrence of another event like the one in San Antonio this June is just a matter of time.

Any comments about this post? Get in touch with us! Send us an email, or post a comment here or on Facebook. You can also tweet us.

How to cite this blog post (Harvard style):

G. Sanchez. (2022) San Antonio’s events were bound to happen. It was just a matter of time.. Available at:https://blogs.law.ox.ac.uk/border-criminologies-blog/blog-post/2022/07/san-antonios-events-were-bound-happen-it-was-just. Accessed on: 20/04/2024Share

YOU MAY ALSO BE INTERESTED IN

With the support of